In January 2016, Taiwanese voters ushered in a new era when they elected Tsai Ing-wen 蔡英文 from the Democratic Progressive Party 民進黨 (DPP) as their President. Ending eight years of Kuomintang (KMT) rule under Ma Ying-jeou 馬英九 (2008–2016), voters were emphatic: Tsai came to power in a landslide, and the Democratic Progressive Party

(DPP) won a majority in the legislature for the first time.

Tsai’s policy platform addressed rising social inequality, Taiwan’s economic malaise, marriage equality, and the need for better environmental protection. Campaigning against a divided and directionless KMT, her strong victory was not a surprise in terms of the dramatic results that democratic electoral politics sometimes produce. However, Taiwanese politics exists within the larger context of the territorial claim over Taiwan by the People’s Republic of China, the strategic rivalry between China and the US, and the aspirations of the majority of Taiwanese people for a statehood that is recognised by the international community. For voters, Taiwan’s unique geopolitical circumstances means that their democratic choices have meaning that goes beyond an endorsement of the domestic platforms of particular parties.

Tsai Ing-wen has responded to Taiwan’s geopolitical circumstances in both her domestic and international rhetoric. She trod a carefully calibrated line during the election campaign that she has maintained during the first year of her presidency, expressing support for the status quo of cross-Strait relations and calling for continuing peaceful relations in the interests of both sides of the Taiwan Strait.

Taiwanese voters, by electing Tsai and the DPP to power, reaffirmed their commitment to the integrity of their democracy and of Taiwan’s civil society. They endorsed the central concerns of the Sunflower Movement of 2014 that rapprochement with mainland China did not represent progress towards permanent peace in the Taiwan Strait, but was instead due to the machinations of opaque party and business interests.

Beijing responded to the inauguration of Tsai with both the Party and the state invoking the 1992 Consensus 九二共識. The Taiwan Work Office of the CCP Central Committee (Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council) 國務院台灣事務辦公室 (TAO) issued a joint statement urging that the achievements of the Ma era be maintained, including twenty-three agreements on trade and cross-Strait exchanges, and stating that Beijing ‘will continue to adhere to the 1992 Consensus and resolutely oppose any form of secessionist activities seeking “Taiwan independence” ’.

The 1992 Consensus refers to the outcome of a meeting in Hong Kong in 1992 between two nominally non-governmental organisations that facilitate relations between Taipei and Beijing: the mainland’s Association for the Relations Across the Taiwan Strait 海峽兩岸關係協會 (ARATS) and Taiwan’s Strait Exchange Foundation 海峽交流基金會 (SEF). The 1992 Consensus holds that both sides agree there is one China and that Taiwan is a part of China, and they also agree to leave unexamined their respective definitions of the meaning of ‘China’.

In mainland China, the phrase ‘1992 Consensus’ began to replace ‘One Country, Two Systems’ 一國兩制 from the mid-2000s as the key prescription for cross-Strait relations. In Taiwan, whether any ‘consensus’ was reached is the subject of vitriolic and partisan debate. Nevertheless, during the period of the government of Ma Ying-jeou, against the backdrop of the military threat from mainland China as well as billions of dollars of trade, the phrase was taken up by both sides and used to assert the presumption of a shared worldview from which Beijing and Taipei could facilitate institutional relations. It became the basis for a pragmatic policy framework that enabled the establishment of numerous trade and investment agreements between Taipei and Beijing.

But on a more abstract level, by proposing that Taipei and Beijing can agree that they might disagree, the 1992 Consensus wove together two possible meanings of China — the CCP Party-state of the People’s Republic of China and the KMT Party-state of the Republic of China — and sought to transcend their national histories. It suspended the historical animus between them and conveyed the notion that China is something much more than just a modern nation-state.

In the artifice of magnanimously agreeing to disagree expressed in the 1992 Consensus is the belief that there is a higher Chinese civilisational moral and social order. It alludes to an elaborate and expansive concept of China that has long captivated the imagination of Chinese people, that Taiwan and mainland China both belong to 天下 tianxia, or all under heaven.

For Beijing, the concept validates the authority of the regime: China means order and unity and the PRC Party-state presents itself as its instrument. In the 1992 Consensus, the idea that there may be a greater civilisational order encompassing Taiwan and mainland China that transcends the nation-state — a tianxia — is one that casts an aura over what would otherwise simply be the tacit acceptance that agreeing to disagree is the best Beijing can hope for and that unification is not currently a realistic prospect.

But instilling the 1992 Consensus with an aura of a transcendent concept of China requires ideological work. The histories of the Republic of China and the People’s Republic of China must be wrought together into a coherent whole.

So when Xi Jinping met with former president Ma Ying-jeou in Singapore in 2015, he spoke of the ‘last seven years’ of cross-Strait relations, the ‘power of kinship in the 1980s’ that ‘finally pushed forward the dialogue across the Strait’, and of how ‘history has left bad memories and deep regrets for untold families on both sides of the Taiwan Strait’. Xi’s comments, vague as they were, excised Taiwan’s Japanese colonial history, the democratic transformation of Taiwan in the 1990s, and the existence of the first DPP government, of Chen Shui-bian 陳水扁, from 2000–2008. He did not mention the failed uprising against the Chinese Nationalists by the Taiwanese in 1947 — the ‘28 February Incident’ 二二八事件, which resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of Taiwanese. Xi also issued a veiled warning to Taiwanese voters:

No matter how much difficulty we have gone through, no power can separate us because we are closely knit kinsmen, and blood is thicker than water. Now we are at a juncture in our relationship. We cannot repeat historical tragedy. We cannot lose the fruits of our development. People across the Strait should continue to push forward a peaceful development and enjoy the fruits of peace together. We should learn and reflect from the history of the cross-Strait relationship. We must be responsible for history, and make wise decisions that will stand the test of time.

28 February 2017: President Tsai attends a memorial service to mark the seventieth anniversary of the ‘28 February Incident’

Source: Presidential Office of the Republic of China, Flickr

At the very least, in other words, they should elect the KMT candidate for president.

The KMT remains willing to affirm the 1992 Consensus in its party policy and political rhetoric. By contrast, in her inauguration speech on 20 May, President Tsai Ing-wen did not name the 1992 Consensus, merely acknowledging:

In 1992, the two institutions representing each side across the Strait [SEF & ARATS], through communication and negotiations, arrived at various joint acknowledgements and understandings. It was done in a spirit of mutual understanding and a political attitude of seeking common ground while setting aside differences. I respect this historical fact.

With a quiet finesse, Tsai reduced the 1992 Consensus to a mere description of an historical moment and rendered the phrase inert, devoid of its historical aspiration and greater political purpose.

Beijing’s response was to re-assert the importance of the 1992 Consensus and the need for Taipei to commit fully to it. In September, on the six-month anniversary of President Tsai’s inauguration, the TAO hosted a meeting in Beijing of eight city and county mayors and deputy mayors from Taiwan, all members of the KMT. The Director of the TAO, Zhang Zhijun 张志军, praised their continuing commitment to the 1992 Consensus and lamented how the ‘change of circumstances’ had harmed the achievements of the previous eight years. For their part, the eight mayors and deputy mayors affirmed ‘that the counties and cities they represent will continue to uphold the 1992 Consensus and work together with the mainland to safeguard cross-Strait peaceful development, in order to benefit the people.’

Beijing continues to find creative ways to deploy policy and political language in order to assert its view on Taiwan’s place in the Chinese world. The difficulty for China, however, is not simply that the people of Taiwan reject the prospect of living under Beijing’s tianxia, but the fact that they are not listening to Beijing at all.

On 15 July 2017, Taiwan commemorates the thirtieth anniversary of the lifting of martial law on the island. The Taiwanese have long given voice to a compelling narrative of Taiwan’s transformation from a largely agricultural economy to an export-driven industrial powerhouse and from a dictatorship to a liberal democracy. However, the violence and trauma inflicted on individuals and families by Taiwan’s KMT-led authoritarian state from the 1950s to the 1980s has not receded from memory. Rather, it has grown in importance for the Taiwanese as the years have passed. The narrative of Taiwan’s modernisation has given way to a preoccupation with the legacy of authoritarianism.

15 August 2016: President Tsai travels to Sandimen Township in Pingtung County to attend a harvest festival held by the Paiwan tribe and Rukai tribe

Source: Presidential Office of the Republic of China, Flickr

The Taiwanese have started to understand their modern history in a distinctive way: as shared experiences that have been concealed and unspoken and which now must be revealed and uncovered. As a result, in recent years the past and its enduring anxieties have come to saturate Taiwan’s contemporary cultural and social life. Museum exhibitions, popular culture, literature, and art have all incorporated the martial law period as part of a re-examination of the story of Taiwan.

For example, the former detention centre for political prisoners in Xindian, in southern Taipei, became the Jingmei Human Rights Museum in 2009, with a large memorial naming every individual who passed through the centre on the way to the prisons on Green Island for opposing the policies and ideology of the KMT government during the martial law period. Those prisons have themselves been restored as museums after years of neglect. The Ministry of Culture 文化部 established storytaiwan.tw in 2012 — a national memory project to record stories that the ministry says, ‘may have been hidden, or may have been forgotten, to open the time capsules of every individual, using sound, images and text to recover those lost experiences and heal past suffering’. The return to power of the KMT under Ma Ying-jeou from 2008 to 2016 seemed to give extra impetus to Taiwanese wanting or needing to look back to their past.

In her inauguration speech, Tsai Ing-wen stressed Taiwan’s painful history. She proposed to establish a truth and reconciliation commission to address the experience of Taiwanese people during the martial law period. In August 2016, she formally apologised to Taiwan’s indigenous peoples for their treatment at the hands of Chinese settlers from historical times onward: ‘For the four centuries of pain and mistreatment you have endured, I apologise to you on behalf of the government.’ She looked beyond the martial law period to the entire era of European and Chinese settlement beginning in the seventeenth century and through to the present.

The idea that the purpose of writing history is to assuage past suffering, to offer a kind of national psychoanalytic therapy, is radically different to the approach to writing history on mainland China. There, official historical accounts serve the ideological and pragmatic needs of the Communist Party and state. Writing history on the mainland can also mean invoking the historical legacy of Chinese civilisation to situate both everyday life and China’s modern national history within a unique and immutable Chinese order that serves state interests.

These two incompatible views of the nature and purpose of history across the Strait illustrate how deep the predicament of cross-Strait relations has become. The truths that are self-evident to the Chinese Communist Party and many Chinese on the mainland, about the nature of an ordered Chinese world that includes Taiwan, are not at all self-evident for the Taiwanese.

The majority of Taiwanese recognise that there is a legacy of Chinese history and culture in Taiwan, but they see it as only one thread of a fabric of social, cultural, and political life that they call ‘Taiwanese’. The rest has been woven out of their experience of Japanese colonialism, the violent history of authoritarianism, economic modernisation, and democracy.

At the end of 2016, as Taiwan continued to speak of preserving the status quo and maintaining peaceful cross-Strait relations while the mainland maintained its insistence that the Tsai government accept the 1992 Consensus, cross-Strait relations were sharply disrupted when President Tsai Ing-wen spoke directly to the then US President-elect Donald Trump. Beijing responded with a formal protest to the US over what it considered a breach of the One-China Policy.

Yet, beneath the political rhetoric and the periodic crises, more fundamental social cultural changes are taking place. Mainland China and Taiwan look ever more uncomprehendingly and unyieldingly at each other’s distinctive preoccupations, and this means a resolution of the Taiwan issue is further away than ever.

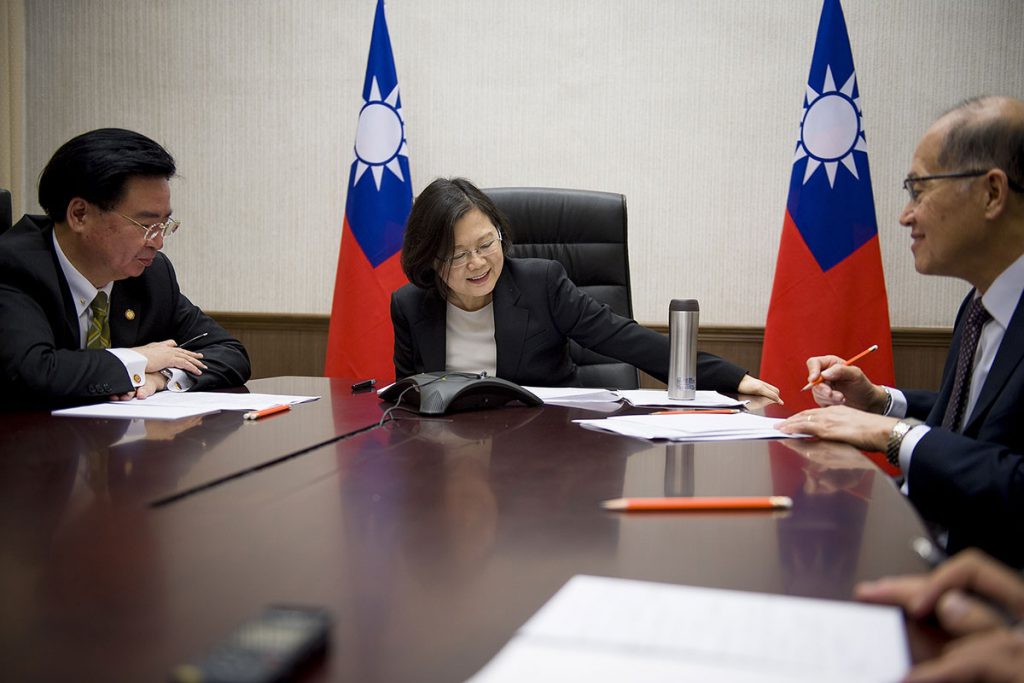

2 December 2016: National Security Council Secretary-General Joseph Wu, Minister of Foreign Affairs David T. Lee, and President Tsai speak with US President-elect Donald J. Trump

Source: Presidential Office of the Republic of China, Flickr

Notes

‘1992 Consensus stressed by mainland after Taiwan poll’, China Daily, 18 January 2016, online at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2016-01/18/content_23124406.htm

Richard Rigby, ‘Tianxia 天下’, in China Story Yearbook 2013: Civilising China, Canberra: Australian Centre on China in the World, 2013, online at: https://www.thechinastory.org/yearbooks/yearbook-2013/forum-politics-and-society/tianxia-天下/

‘Transcript of Xi Jinping’s opening remarks,’ Today News, 7 November 2015, online at: http://www.todayonline.com/singapore/transcript-china-president-xi-jinpings-speech-he-meets-taiwans-ma-jing-yeou

‘Full text of President Tsai’s inaugural address,’ Focus Taiwan, 20 May 2016, online at: http://focustaiwan.tw/news/aipl/201605200008.aspx

‘Minister of Taiwan Affairs Office, Zhang Zhijun, and a delegation of county mayors from Taiwan hold talks 国台办主任张志军与台湾县市长参访团座谈’, Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council, 18 September 2016, online at: http://www.gwytb.gov.cn/wyly/201609/t20160918_11571368.htm

‘Full text of President Tsai Ing-wen’s apology to indigenous people,’ Focus Taiwan, 1 August 2016, online at: http://focustaiwan.tw/news/aipl/201608010026.aspx