THE EXHIBITION ‘Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China’, which opened in December 2013 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) in New York, reflected a basic theme of the contemporary Chinese art scene in 2014: nostalgia and continuity with the past. By juxtaposing contemporary ink works in various media (including painting, photography, sculpture, installation and video) with fifth-century Buddhist sculptures from its permanent collection as well as Han-dynasty ceramics and Ming furniture, The Met attempted to place Chinese art today within its historical context.

In 2014, exhibition titles in China itself frequently featured terms such as ‘ancient’, ‘history’, ‘past’, ‘new youth’, ‘childhood’, ‘anniversary’ and ‘generation’. Moreover, curators routinely referred to classic texts and philosophy, including works by the military strategist Sunzi 孙子 and the Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi 庄子. Whether, as some claimed, this represented a literati or dilettantish escapism or a vision of a brighter future, art exhibitions in 2014 sought to re-treat, re-view, re-visit, re-evaluate, re-examine, re-contextualise, re-frame, re-invent, re-interpret and re-think the Chinese past as a strategy for making sense of an increasingly complex present.

The independent curator and art historian Martina Köppel-Yang claims that this strategy looks forward rather than backward. In her curatorial essay for the exhibition ‘Advance Through Retreat’ 以退为进 at the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai, she refers to The Met’s ‘Ink Art’ as well as other recent exhibitions such as Pi Daojian’s 皮道坚 The Origin of Dao 原道 at the Hong Kong Museum of Art (2013). She notes ‘a tendency that is gaining ever greater importance, a tendency which shows the apparent need to rediscover and revaluate Chinese traditional media as a lingua franca’. She also notes that in the ‘creation of a cultural identity of a new, self-confident, post-WTO-entry China’, political and economic as well as artistic and cultural motivations are at play. Yang drew the title of her exhibition from a famous stratagem in Sun Tzu’s sixth-century BCE text The Art of War 孙子兵法. Ostensibly a retreat to traditional methods and local aesthetics, the exhibition included works that resist the official project of reaffirming a national cultural identity — by the ‘outsider’ calligraphy of the late Hong Kong street artist Tsang Tsou Choi 曾灶財, scrawled over distribution boxes and electricity poles around the streets of Kowloon, and the Cantonese collective the Yangjiang Group, which refuses to follow established artistic rules in its practice, for example.

Beijing’s newly opened privately-owned Redbrick Art Museum also reflected this broad trend in its inaugural exhibition ‘Extensive Records of the Taiping Era’ 太平广记, the title directly referring to a tenth-century collection of folk stories. The curatorial team, led by Gao Shiming 高士明, stressed the power of ‘folk’ or ‘non-official’ 在野 culture, and how such non-official knowledge, created by artists turned augurs, astrologers and narrators, evokes perceptions of fate, reality and uncertainty in contemporary China. The night before the exhibition, Hong Kong artist Pak Sheung Chuen 白雙全 gathered together a group of Daoist priests and held religious rituals to attract stray ghosts. Grains of rice and joss stick ashes from their necromantic rituals were later unintentionally carried by the soles of visitors’ shoes — or perhaps the invisible ghosts — into the space of other works in the show.

A number of new private museums opened across China in 2014, including Shanghai’s Long Museum and Yuz Museum, both located on the West Bund and showcasing their respective owners’ private art collections. In their inaugural exhibitions too, history reigned: the Long Museum opened with ‘Re-View’ 开今 • 借古, literally ‘borrowing from the past, opening up to the present’, while the title of the Yuz Museum’s ‘Myth/History’ 天人之际, literally ‘between heaven and human’, quotes from a letter written by the classical historian Sima Qian 司马迁 to his friend Ren An 任安 in 93 BCE. Here Chinese history and philosophy provide a context for the discussion of current issues and the future development of Chinese art.

Three researchers from the Shanghai Museum disputed the authenticity of an eleventh-century calligraphy work on display in the Long Museum, Gongfu Tie 功甫贴 by Su Shi 苏轼, which the collector and museum-owner, Liu Yiqian 刘益谦 bought at Sotheby’s in New York last year. This month-long dispute exemplifies mounting tensions between state-owned museums and the emerging private sector, in which anyone with the money and interest can open their own museum. Those within the state sector and the academy have raised serious questions about the quality of institutional research in the private sector as well as issues including authenticity, management and curatorial strategies; there is also no doubt that there is tension between the worlds of officially sanctioned culture and private cultural entrepreneurship on principle and ideology.

To demonstrate its own intellectual strength and the potential for innovation within the state sector, the National Art Museum of China launched its third International Triennial of New Media Art, titled ‘Thingworld’ 齐物等观, in June 2014. Curator Zhang Ga 张尕 explained: ‘In Chinese language, the word for “thing” is a compound of the characters East and West, a geographic stretch across the infinite space of two imaginary ends in the ancient mind. Thing is everything.’ The exhibition showcased fifty-eight works by sixty-eight artists and artist collectives from twenty-two countries and regions (for instance, Taiwan). The work included machines, robots, installations using garbage, furniture, rocks and flowers as well as new media.

Zhang Ga’s curatorial essay for ‘Thingworld’ drew on Zhuangzi’s concept of the ‘equality of all things’ 齐物论, another example of ‘the use of the old to serve the new’ in contemporary Chinese curatorial practice. At the same time, he scored some subtle ideological points by slamming the ‘frivolity’ of contemporary cultural debates over representation and identity, humanism and so forth in the face of man-made climate change and ecological disaster.

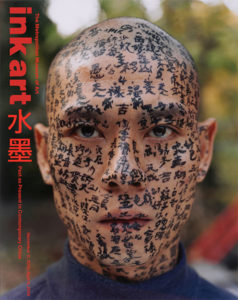

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition ‘Ink Art’ positioned contemporary Chinese art in a historical continuity

Source: metmuseum.org

Anxiety about the worsening environment is reflected in the recent work of a number of Chinese artists as well as exhibitions. The Central Academy of Art in Beijing and Nanjing University consecutively hosted ‘Unfold’, a travelling exhibition of climate change-inspired art curated in Great Britain. The relationship between people 人 and nature-heaven 天 was also a theme in the exhibition ‘Landscape: the Virtual, the Actual, the Possible?’ 风景:实像,幻像或心像? at the private, Rem Koolhaus-designed Times Museum in Guangzhou. Implicit in this sort of work is a sense of a better, cleaner, simpler past.

Looking backward need not be a negation of the present, of course. Like ‘Ink Art’, Shenzhen OCT Contemporary Art Terminal’s exhibition ‘From the Issue of Art to the Issue of Position: Echoes of Socialist Realism’ 从艺术的问题到立场的问题:社会主义现实主义的回响, positioned contemporary Chinese art in a historical continuity. Carol Yinghua Lu 卢迎华, who curated the exhibition in collaboration with her husband, artist Liu Ding 刘鼎, argued that Socialist Realism, both as an artistic language and an ideology, exerts lasting influence on contemporary art practice. This curatorial position challenges the conventional perception that contemporary Chinese art is rebellious towards officialdom. While this argument is not entirely new, it was ground-breaking to realise it in the form of a museum-scale exhibition.

Whether revisiting the traditional medium of ink and referencing ancient philosophy, reflecting on a rapidly changing environment or re-examining the not-so-distant Socialist Realist past, recent exhibitions of Chinese art have looked at the past to ask important questions about ownership over the future.