This week’s topics: Nanjing Massacre, democratic solidarity, Zoom/censorship, CCP members

1. Nanjing Massacre

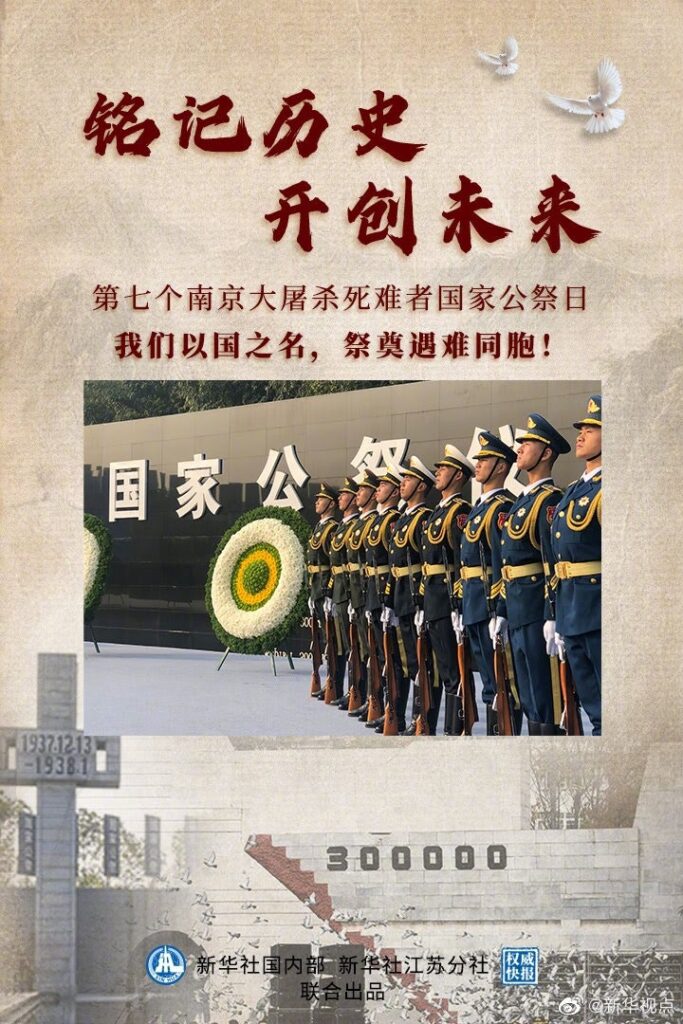

China marked its National Day of Commemoration for the Victims of the Nanjing Massacre 南京大屠杀死难者国家公祭日 with a solemn public ceremony in Nanjing on December 13. Eighty-three years have passed, but the collective memory of the event still exerts an emotional pull on the Chinese psyche today.

Source: the poster is designed by Zhang Huihui 张惠慧 for Xinhua. The top two lines read: “Remember the history, create the future 铭记历史 开创未来”.

David Lowenthal, a renowned historian and heritage scholar, in his book The Past Is a Foreign Country, argued that the interpretation of the past is a constant process. The past is not dead, but alive and used in the present.

The way that Beijing recognises and commemorates the Nanjing Massacre has evolved over time. From the establishment of the PRC until the early 1980s, the process is one of forgetting or “collective amnesia”. Mao’s new state promoted historical narratives such as world revolution and class struggle. Japan’s war with China, mostly fought with the KMT (Nationalist Party), did not fit neatly into these narratives.

From the early 1980s until 2010s, we saw a process of reappraisal of the Nanjing Massacre. Beijing took the event out of cold storage and placed it at the centre of a new historical narrative, based on national struggle and humiliation. The CCP’s ideology was losing legitimacy in the 1980s after Mao’s death. In the aftermath of 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, the Party scrambled to shore up its legitimacy, including through patriotic education.

In recent years, Beijing has sought to legitimise its narrative of the Nanjing Massacre globally. For example, in October 2015, UNESCO accepted Beijing’s submission of documents about the Nanjing Massacre to the Memory of the World Register. For China to become a global power, economic and military power is not enough; it must make its version of history widely recognised, and preferably accepted, around the world.

All states make and use collective memory for social and political purposes. China is no different. However, compared to governments of liberal democracies, the Chinese party-state has overwhelming power in shaping collective memory. It can push its version of history through censorship, education institutions, and state media, and use coercive tools to shut down alternative viewpoints or dissent.

The current version of China’s modern history espoused by Beijing has three dominant characteristics. First, it is Han-centric and marginalises the contribution or even the involvement of other ethnic groups in China. Second, it is twisted to suit Beijing’s purposes. The collective memory surrounding the events of 1989 Tiananmen Protests, the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution are some examples of this. Third, Beijing’s version of history has become more nationalistic in recent years — the dream of a world communist revolution has been replaced by a state-sanctioned dream of national rejuvenation.

The relationship between power and history is highlighted by George Orwell’s classic novel 1984: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.”

2. Democratic solidarity

After the recent trade actions by China targeting Australia and the release of China’s 14 grievances, the call for some sort of “democratic alliance” has become much stronger. The Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC), launched in June this year, has been at the forefront of this rhetoric. We had earlier noted that IPAC is very West-centric, with Japan and Uganda the only two non-Western countries currently represented.

Earlier this month, IPAC released a video calling for people around the world to show solidarity with Australia by drinking Australian wine. This week, MPs from Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, European Parliament, France, Germany, Italy and New Zealand signed a letter to their foreign ministers to “stand together with democracies everywhere” and support Australia.

Rhetoric or moral support will no doubt be appreciated by the Australian Government, but it is still cold comfort for Australian producers. However, it is possible for other countries to show solidarity with Australia beyond rhetoric. Jordan Schneider and Yun Jiang, for example, wrote about ideas such as a “strategic Shiraz reserve” or a “mutual trade defense treaty”.

But such “solidarity” is rife with coordination problems. Countries would naturally act in their own national interest. For example, other countries are very eager to fill the gap left by Australia in the Chinese market. And any push to buy Australian wine will be forgotten the instant that the interest of domestic wine producers is affected. In fact, the likely beneficiaries for China’s trade restrictions against Australian wine include the US and New Zealand wine exporters.

In addition, some politicians appeared to be “tough” on China only to score domestic political points, but show very little concern for real human lives affected. US Senator Ted Cruz, for example, has just blocked a bill helping people in Hong Kong fleeing persecution. In recent months, he has portrayed himself as an advocate of the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong.

How much we value something is revealed by the cost we are willing to bear in pursuing it. The rhetoric of democratic solidarity is just that before members of team democracy put their money where their mouths are.

3. Zoom and censorship

The US Department of Justice has charged a China-based employee of Zoom with “with conspiracy to commit interstate harassment and unlawful conspiracy to transfer a means of identification”. The Department alleges that the employee disrupted a series of video conferences commemorating the 1989 June Fourth Massacre.

Zoom has responded to these allegations, indicating that the said employee had been acting contrary to company policies. Whether the Department of Justice allegations are true or not, and whether the fault lies with the individual employee or the company are yet to be determined.

In addition to censorship on behalf of the Chinese Government, Zoom has also been accused of censorship on behalf of the US Government. Citing US anti-terrorism laws, Zoom shut down a seminar at San Francisco State University over the participation of Palestinian activist Leila Khaled.

For companies like Zoom, they have to abide by the laws of the countries they operate in. But their compliance with local laws may also cause reputational damage to their operations and also potentially break the laws of other countries. The jurisdictional issues that technology firms such as Zoom have to deal with are highly complex and fraught.

For Zoom, compliance with local regulations appears to include shutting down meetings, such as ones to commemorate Tiananmen Square in China or ones involving Khaled in the US. In China, it also involves real ID requirements. China has also required Zoom to transfer China-based user data to a data centre in China (data localisation, which is a common requirement in many countries).

Social media and other technologies have raised a raft of privacy and censorship issues. But unlike Facebook or Twitter, Zoom is not blocked in China, which means it has to deal with issues associated with operating both inside and outside China, while trying to maintain a reputation for protecting privacy and promoting the free exchange of ideas.

4. CCP members

Media reports came out in recent days about a supposed “leak” of an alleged CCP member list with two million names. A number of reports framed the story as one of CCP infiltration across the world. The concern is that CCP members working at foreign embassies and consulates as well as major global companies could compromise security. Also on the topic of CCP membership, earlier this month the US State Department issued new travel restrictions for CCP members and their families, limiting them to a single-entry visa that is valid for a month. Other Chinese citizens can still obtain multiple-entry visas that can last up to 10 years.

The problem with many threat narratives about CCP membership is that they are often based on sweeping (and even false) generalisations. And therefore policy actions based on these threat narratives can be counterproductive. Here are a few observations from our personal experience interacting with party members.

First, CCP is an organisation with 92 million members and hundreds of thousands of subordinate organisations. There are more CCP members than the population of countries such as Congo, Turkey, Iran and Germany. This means that there is great diversity between party members, including even in terms of political outlook. In fact, the overwhelming majority of party members join for upward mobility instead of ideological conviction. Party membership is mainly seen as a vehicle to better living standards.

Second and related, party allegiance means very little to the majority of its members. After all, there is no coherent ideology to buy into after the disaster of Mao-era ideological campaigns and policies. In fact, an average CCP member is more critical of the CCP than the average Chinese person. This could be due to different levels of education and that insiders of an organisation tend to be more critical and cynical than outsiders (as they see how the sausage is made).

As we wrote back in July:

The CCP is no longer a secretive avant-garde Leninist organisation, but rather the elite class in China. It permeates every part of Chinese society. It is difficult to separate out the Party on the one hand, and the Chinese people on the other — the relationship between the two is complex. And this makes taking any actions on the entire CCP membership challenging to implement.

Not only are policy actions against the entire CCP membership difficult to implement, but they can be counterproductive. The latest travel restrictions will likely affect thousands of CCP members and their family, most of them at the grassroots level without any power to steer the ship of state.

The supposed threat (“infiltration”) to consulates is also vastly overblown. For Australia, 70 per cent of its staff at embassies and consulates are locally engaged. Locally engaged staff are engaged under local labour law as it applies to diplomatic and consular missions.

The people engaged in these positions would not see classified materials. Any positions that require the handling of classified materials will only hire people with the appropriate clearance. It shouldn’t surprise anyone that different roles in the consulates see different classes of materials, and employees are trained to handle them appropriately.

Of course, a country like Australia can choose to only engage Australian employees with top secret clearance for its embassy and consulates in China to reduce the risk even further. But the cost would be astronomical. It would include two years of paid full-time language training, accommodation, schools for dependents, and regular flights back to Australia. And the benefit is marginal since the roles involve mostly public information anyway.

Quote of the week

生、老、病、死、怨憎会、爱别离、求不得、放不下

Birth, aging, illness, death, resentment from being with undesired ones, being separated from loved ones, not getting what one desires, the inability to let go.

We’ve been watching some Chinese dramas recently. One hugely popular genre is romance mixed with xianxia fantasy. Examples of this genre include Eternal Love (三生三世十里桃花) and Ashes of Love (香蜜沉沉烬如霜), both available on Netflix and YouTube.

The two shows follow a very similar plot. The plot would seem very odd unless you are familiar with the Chinese folklore and beliefs, which is a syncretisation of Buddhism, Taoism, and other local traditions.

The main characters are so-called “immortals” (a Taoist concept), who have supernatural powers and can live very long lives. But every now and then, they must be reborn in the “mortal world” where their memory and power are “sealed”, and they live as mortal beings. It’s usually done as a punishment or a “trial” (历劫). The mortal beings (that’s most of us, I assume!) don’t have that luxury and are stuck in saṃsāra (cycle of birth, death and rebirth).

Mortal life (that is, the life we’re living!) is portrayed as harsh and full of suffering. This is a common perception in Chinese folk beliefs and Buddhism. Indeed, it is the first of the Four Noble Truths in Buddhism, that life is dukkha (suffering).

Inspired by Buddhism’s concept of dukkha, descriptions of the suffering of the mortal world often refer to the “eight sufferings” (八苦, literally “eight bitterness”). There are some different variations in the formulation, the above is a common one. Another formulation replaces the last one with 五阴炽盛 (five aggregates of clinging or skandhas). In another formulation, only the first seven are included.

This week on China Story:

Melissa Conley Tyler, Australia-China relations are more than just government: With the official relations at a new low, it is easy to be pessimistic about Australia-China relations. But there are many actors involved in Australia-China diplomacy. These connections can help provide communication channels for when official relations are frosty. They also bring economic, educational and cultural benefits.