IMAGE-BUILDING continued to top the Chinese government’s international agenda in 2021. In May, President Xi Jinping 习近平 instructed officials of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to work towards improving ‘the appeal of Chinese culture, the affability of China’s image, the persuasive power of Chinese discourse, and the guiding power of our international public opinion efforts’.1 Despite Beijing’s efforts, there are significant mismatches between China’s self-claimed achievements and its performance as witnessed by peoples of the Global South and even as assessed by some scholars within the PRC.

Persistent international calls for more transparent investigations into the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic, along with the heightened geostrategic rivalry between China and the United States and its traditional allies and partners, have led Beijing to ramp up efforts to engage with the Global South. Its goal is to project a benign image as a responsible great power.

Not surprisingly, a focus for China in 2021 was proactive COVID-19 diplomacy centred on the delivery of vaccines and medical supplies. Employing a whole-of-government approach involving administrative bodies at different levels, diplomatic missions, companies, and other actors, the PRC increased its assistance to developing countries in the fight against the pandemic. Wang Yi 王毅, Minister for Foreign Affairs, who also oversees the China International Development Cooperation Agency, boasted in August 2021 that the PRC had donated Chinese-made vaccines to more than 100 countries and sold more than 770 million doses to more than 60 countries. China, he said, aimed to supply two billion doses overseas by the end of 2021.2

Another priority of China’s diplomacy in 2021 was the continued promotion of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to build a ‘community of shared destiny’. Promoting the BRI was China’s focus at the 2021 conference of the Boao Forum for Asia.3 According to China’s Ministry of Commerce, China’s direct investment in BRI partner countries grew by 8.6 percent in the first half of 2021.4 On the ground, Chinese contractors have been working long hours to catch up on BRI projects delayed by pandemic-related travel restrictions and lockdowns.

The Pacific Islands — fourteen sovereign nations and seven territories with a total population of thirteen million people, and one of the most aid-dependent regions in the world — could be considered a test region for the effectiveness of China’s efforts. In recent years, traditional development partners in the region, such as Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, have stepped up their efforts to engage with Pacific Island countries to counter China’s rising influence in the Pacific. The region has become a playing field in the power game between traditional development partners and China in the broader Indo-Pacific. While the approach of traditional development partners typically demands reforms in governance, the PRC focuses instead on economic links (trade, commercial loans, aid, and investment), and this is naturally appealing to leaders of many Pacific Island states.

In 2021, Beijing focused on delivering China-made vaccines to the Pacific region. Of the ten Pacific Island nations that have diplomatic relations with the PRC (another four have relations with Taiwan), China has donated Sinopharm vaccines to four: Solomon Islands (in April 2021, 50,000 doses), Vanuatu (in June 2021, 20,000 doses; in November 2021, 80,000 doses), Papua New Guinea (in June 2021, 200,000 doses), and Kiribati (in September 2021, 60,400 doses). In Papua New Guinea, in particular, China and Australia competed for influence through vaccine roll-out programs, with Australia delivering 28,000 AstraZeneca doses as of July 2021 and pledging a total of one million doses.5 As of July 2021, Australia had also donated 63,000 and 20,000 AstraZeneca doses to Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, respectively.6 While most of those taking Chinese vaccines in Papua New Guinea are members of the Chinese diaspora, Vanuatu Prime Minister Bob Loughman and Solomon Islands Deputy Prime Minister Manasseh Maelanga received Sinopharm jabs to boost the general public’s confidence in vaccination. However, it is unclear whether media reports about the lower efficacy of Chinese vaccines have had an impact on the uptake of these vaccines in the Pacific.

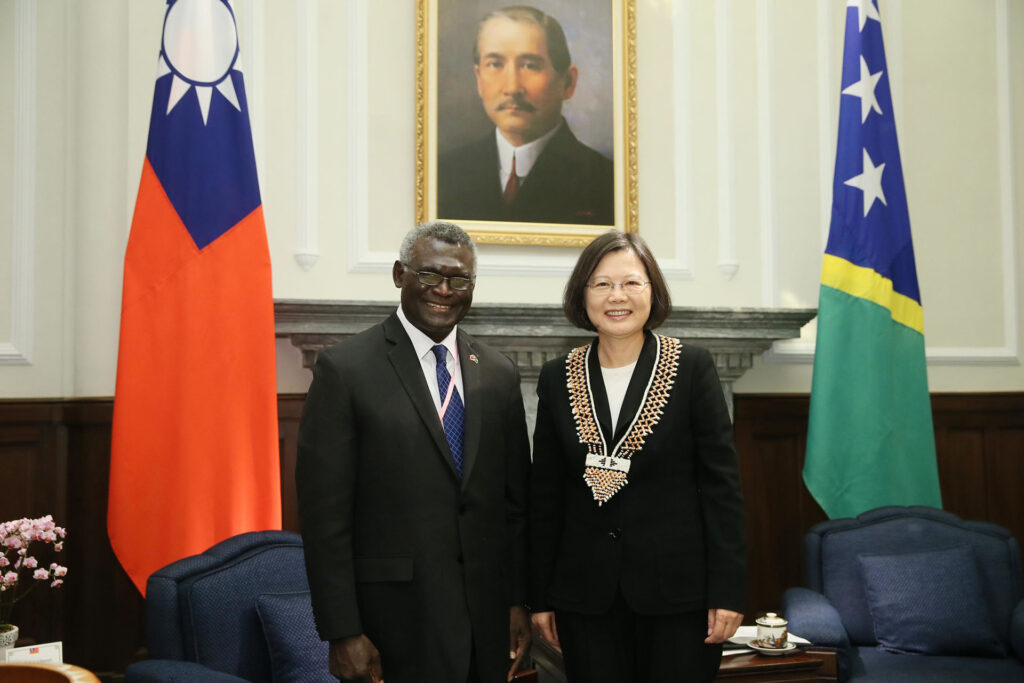

With respect to the BRI in the Pacific, Chinese contractors have sped up the progress of projects such as the China-funded National Sports Stadium in Honiara, the capital of Solomon Islands. Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare and his deputy attended the ground-breaking ceremony for the stadium in May 2021.7 This multi-million-dollar stadium is highly significant in terms of China’s diplomatic efforts, as it was one of the main aid commitments made by China to the Sogavare government following its decision to switch diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the PRC in September 2019. It will be used to host the 2023 Pacific Games. The project contractor, China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation, has committed to completing the project as scheduled.

For all such efforts on the part of Beijing, local perceptions of China remain mixed in the Pacific, contradicting China’s claims of success. The public response of Pacific Island governments to China’s diplomacy is more positive than that of many non-governmental actors such as civil society organisations and academics.8 China’s aspirations in the region provide governments with options both for development assistance and for bargaining power with traditional development partners who have concerns about China’s motives and growing influence. In particular, Pacific Island officials have welcomed Chinese aid in infrastructure building, which is vital for broader development. Compared with non-governmental actors in the Pacific, and to minimise any negative impacts on bilateral relations, Pacific Island government officials tend to avoid openly discussing debt issues in relation to Chinese loans to their countries.

Based on the preliminary results of the author’s research, non-governmental actors in the Pacific have much more nuanced and, in many cases, critical views of China. For example, a survey of twenty-one law degree students at a university in Fiji in 2021 revealed that 38 percent (eight) had concerns about their country’s participation in the BRI. Some suspect China is using the BRI as a cover to achieve larger geostrategic aims while others worry that Fiji is becoming over dependent on China. Similar concerns can be found in the literature.9 On the survey question of which countries (including Australia, New Zealand, the United States, China, and others) are important to Fiji (multiple choice), thirteen of the surveyed twenty-one students included Australia in their answers, eleven included New Zealand, while only seven included China. In other research, the author surveyed eighty-eight students studying international relations at a university in Papua New Guinea in 2021. Forty-five students expressed concerns about the BRI in the country, citing inadequate transparency and accountability for the projects, the need for rules and regulations to protect affected people in project areas, the need to use more local contractors, and the opacity of China’s strategic intentions behind BRI projects.

Even within the PRC, scholars hold a more nuanced view of China’s achievements in the Pacific than the Party-State. In a survey of thirty-nine Chinese scholars of Pacific studies conducted by the author in 2019, twenty-four gave a score between 60 and 79 on a scale of 100 points for the performance of China’s Pacific diplomacy.10 Take Chinese aid to the Pacific region as an example. These scholars suggested Chinese actors should increase their engagement with local communities, develop a better understanding of local conditions and needs, and provide tailored assistance to the region.

Image-building is never an easy task. For China to deliver foreign aid such as medical supplies and stadiums is one thing, but to win hearts and minds is another. The latter demands a much better understanding of and sensitivity to local conditions and expectations. Otherwise, the contradiction between China’s image-building expectations and reality will remain.