THE CHINESE COMMUNIST Party’s Sweep Away Black and Eliminate Evil 扫黑除恶 campaign entered its second year in 2019. When it launched in 2018, the three-year campaign promised to take down criminal or ‘black society’ gangs 黑社会 involved in gambling, prostitution, and extortion, as well as other ‘black and evil forces’, such as the coercive monopolies of ‘sand tyrants’ 沙覇 who force construction companies to buy building materials through them at inflated prices, and ‘underground police’, 地下执法队 who enforce informal rules in street markets.

Billboard on Kunming street showing loan sharks. The sign reads: ‘Remove the cancer of black and evil forces’ and provides hotlines and an email for reporting crimes

Source: Ben Hillman

Loan sharks and usury 高利贷 are also high on the hit list. Loan sharks charge high interest for fast cash, and loan terms are typically short. Borrowers find themselves in serious trouble if they fail to repay the loans on time. A common loan shark tactic is the ‘nude loan’ 裸贷, which comes with the condition that borrowers (who are usually young and female) provide the loan shark with nude photos of themselves that will be posted on the Internet in case of default. Law enforcement in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) calls such offences ‘soft violence’ 软暴力. And it can get a lot worse for loan shark victims. According to a local policeman I interviewed in Yunnan province:

[G]angs will do anything to terrorise people who owe them money, [including] flushing people’s heads in the toilet and making them eat shit. Sometimes they imprison people in a room until they come up with a plan for repayment.

False (illegal) imprisonment is apparently so common that, along with nude loans, it has been specifically identified as one of the ‘black and evil’ acts to be eradicated in the campaign.

In a Yunnan village I visited in March 2019, locals confirmed the policeman’s report, and offered many examples of people who had met sorry fates at the hands of loan sharks. The villagers also confirmed that the Sweep Away Black and Eliminate Evil campaign was having a good effect. ‘The gangs are quiet now’, a former township head told me: ‘They know this [crackdown] is serious.’ The state news agency Xinhua reported that, by the end of March 2019, the campaign had uncovered 14,226 cases of ‘black and evil’ activity involving 79,018 people.1

Sweep Away Black and Eliminate Evil targets not only evil forces 黑恶势力 within society, but also the ‘protective umbrellas’ 保护伞 and ‘relationship networks’ 关系网 that sustain them from within the state — government officials and members of the police force who aid and abet gangsters. Complementing President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive, the campaign seeks to break up the patronage networks of ‘little kingdoms’ 小王国 that have evaded previous efforts at eradication.2 China’s provinces have jockeyed with one another to achieve the highest number of arrests of officials serving as ‘protective umbrellas’, with regular public announcements about the latest busts. In April 2019, Liaoning province’s Office for Discipline Inspection announced that it had investigated and responded to more than 1,000 ‘black and evil’ cases, including some involving ‘big fish’ such as Ji Hongsheng, former Deputy Chief of Dandong City Public Security Bureau. Ji was sentenced to ten years for helping criminals avoid prosecution.3 In the dock, Ji said: ‘I thought I was helping out a friend — no big deal. I didn’t think it was a crime, but now I regret it.’4

It is a common grievance on the streets of China that well-connected people receive only light punishment when they fall foul of the law. Media attention given to cases such as Ji Hongsheng’s is designed to reassure the public that the Party is determined to root out local corruption and see justice served. A government official told me in March 2019 that the crime-busting element of Sweep Away Black and Eliminate Evil was very popular with ordinary citizens.

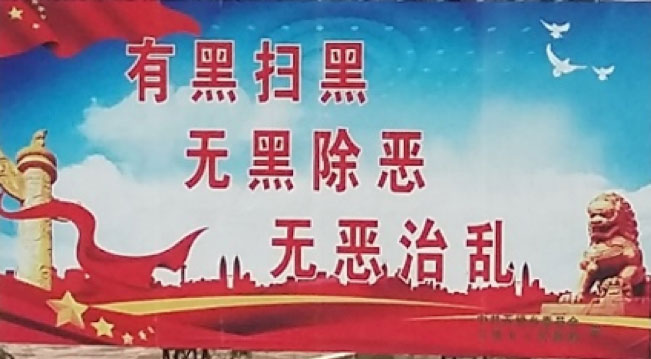

But not all elements of the campaign have been popular. In 2019, the campaign’s scope expanded to include social disorder 乱. The expanded mandate — revealed in a number of Party documents released throughout the year — is reflected in campaign propaganda across the country. The road sign on the next page is typical of the revised propaganda; it reads: ‘Where there is black, sweep it, where there is no black, eliminate evil, and where there is no evil, cure disorder.’ Security forces are on notice: there is always someone to catch! Party documents and propaganda suggest that the inclusion of ‘disorder’ is a natural extension of the campaign and reflects the emphasis on rule of law and China’s new social governance systems. Nanjing City, for example, announced in 2019 that it was strengthening its grid-based social governance system to ensure that ‘evil forces’ — including village, city, and transport 行霸 ‘tyrants’ (for example, taxi and delivery monopolies) — had nowhere to hide.5

The spectre of the ‘black hand’ or ‘black and evil forces’ draws on a long history of Chinese political and legal discourse that goes well beyond the sense of ‘gangster’ or ‘miscreant’. The term has been used frequently as shorthand for enemies of the state in Communist Party rhetoric and is now used routinely to dehumanise and delegitimise protestors and dissidents. State media has described the Hong Kong protests of 2019, for example, as being orchestrated by ‘black hands’ with support from ‘foreign black hands’. Protests in China’s Tibetan areas a decade ago were similarly characterised.6 Another Chinese term frequently used to dehumanise enemies is ‘fly’ 拍蝇, which routinely appears in Sweep Away Black propaganda. For example, a Shanghai City government notice highlights central party directives to sweep away ‘local flies’ 基层 ‘拍蝇’ alongside ‘black and evil forces and the corrupt’.7

Roadside billboard in Yunnan Province: ‘Where there is black, sweep it, where there is no black, eliminate evil, and where there is no evil, cure disorder’

Source: Ben Hillman

With Sweep Away Black and Eliminate Evil campaign committees now firmly established and empowered at all levels of administration, security agencies mobilised, and undesirable types filling police detention centres, the campaign is proving useful for the Party as it continues to tighten its political control over local society. The persistence of ‘black and evil forces’ provides justification for the expansion of authoritarian social control systems such as surveillance and social credit schemes. The campaign also coincides with a stricter application of ‘political checks’ 政审 for college applicants and jobseekers. As a local businesswoman told me: ‘Sweep Away Black and Eliminate Evil is the Party’s latest initiative to make us more obedient.’

Local party branches are using the campaign to squash dissent. The ‘black hand’ label is often associated with dissent in China, and once a ‘black hand’ has been identified, it is easy for local Party bosses and law enforcement to make arrests under the auspices of Sweep Away Black. I learned of one case in which villagers who complained about an exploitative land deal were swept up and detained after assembling in a large group to protest. In another village, twenty-three people were arrested in a single police swoop. When I returned to Yunnan later in 2019, villagers who had previously celebrated the campaign’s takedown of gangland activities expressed concern about its mission creep. Some expressed fears that their association with or family ties to someone swept up in the campaign could land them in trouble. Others reported that a young woman had been expelled from a corporate recruitment program because her father had been apprehended by the Sweep Away Black and Eliminate Evil committee. As one villager explained to me:

We worry because someone only needs to report you to the committee for you to be investigated. People have started making false reports against their enemies. It’s like the Cultural Revolution.

Sweep Away Black and Eliminate Evil promotes a vision of a safer, fairer, and more harmonious society, but the campaign’s broad mandate and its combative revolutionary style has begun to arouse memories of a nightmarish past that post-Mao China was supposed to have left behind.