African leaders and Xi Jinping pose for a group photo at the 2018 Beijing Summit of the Forum on China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC)

Source: Department of International Relations and Cooperation

(DIRCO)

ON 3 SEPTEMBER 2018, President Xi Jinping 习近平 delivered a short and rousing speech at the opening ceremony of the Beijing Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). The speech focussed on the ‘common interests’ and ‘shared vision’ of China and Africa, and their mutual responsibility to champion peace and development through ‘brotherly’ cooperation, and ‘win-win’ solutions.

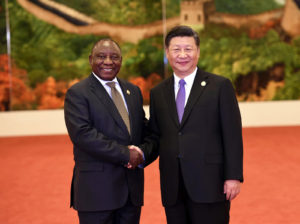

President Cyril Ramaphosa and Xi Jinping at 2018 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation

Source: Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO)

President Xi emphasised the roles played by Chinese firms and capital in solving Africa’s infrastructure and industrialisation problems. He also announced that China will provide African countries with US$60 billion between 2019 and 2021, in addition to $US60 billion promised during the Johannesburg FOCAC Summit in 2015, to address infrastructural, trade and investment, manufacturing, health, and education needs across the continent.

After over four decades of unprecedented economic growth, China has gone from being a relatively minor economic and diplomatic player in Africa to the region’s largest trade and investment partner. The most common view outside of China (including in parts of Africa) is that China is a neo-coloniser or neo-imperialist, epitomised by headlines such as: ‘China’s Ugly Exploitation of Africa — and Africans’ (from The Daily Beast), ‘How China has created a new slave empire in Africa’ (Daily Mail) and ‘China in Africa — The new Imperialist?’ (The New Yorker).

Neocolonial interpretations of China’s activities in Africa focus on how it uses money to ‘buy influence’ across the continent. However, China uses another important tool to seek influence: the narrative of ‘common interest’ or ‘convergence of interests’. Exploring how China uses both money and rhetoric to seek influence in Africa can help us move beyond the neocolonial debate to a more nuanced understanding of Sino-African relations — with Zambia and Ethiopia being cases in point. And is Sino-African relations all win-win, as China’s official rhetoric would have us believe?

Respect, Love, and Support

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a long history in Africa. After World War II, growing movements for independence across the African continent were sometimes met by harsh anti-decolonisation policies from colonial masters, for example the French in Algeria. Young anti-colonial fighters found a friend in CCP chairman Mao Zedong 毛泽东, who had positioned China as the leader of the ‘Third World’. Mao provided military assistance in the form of intelligence, weapons, training, and finance to anti-colonial rebels in Algeria, Angola, Guinea Bissau, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe. This gained him respect among many young African nationalists.

In May 1955, in a fiery anti-imperialist speech at the Bandung Conference in Indonesia, Chinese premier Zhou Enlai 周恩来 told African and Asian leaders that industrialisation was the sine qua non for independence and stability. He said that acknowledging their ‘shared destiny’ through economic and diplomatic cooperation would allow them to industrialise while endorsing the principle of non-interference in each other’s internal affairs.

Under Mao, China provided financial and other material aid to a number of African countries including Zambia, Tanzania, and Guinea. China built the TanZam railway between 1970 and 1975 and established numerous ‘Friendship’-branded projects in Zambia and Guinea. Beijing’s efforts paid off: in 1971, the People’s Republic of China gained its seat at the United Nations thanks to the support of many African countries.

The death of Mao in September 1976, and Zhou Enlai earlier that year, led to a gradual change in China’s domestic and foreign policies. After Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 assumed the leadership in 1978, he refocused China’s foreign policy away from ideology and towards the economic benefits of bilateral relationships. Premier Zhao Ziyang’s 赵紫阳 ten-nation tour in 1982 set the basis for new China–Africa economic, diplomatic, and cultural relations, taking in countries that shared similar ideologies to China, but also those that did not.

Domestically, between 1978 and 1994, the Chinese government introduced reforms to improve the efficiency of its state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and established special economic zones (SEZs) in China’s coastal areas. It also created the Industrial and Commercial of Bank (ICBC) and the Export-Import Bank of China, charging them with supporting the Party-state’s policies on industry, foreign trade, diplomacy, and the economy. SOEs, SEZs, and state-owned banks all play a crucial role in China’s quest for influence in Africa in the twenty-first century.

Deng’s reforms triggered a period of rapid economic growth in China, averaging over ten per cent per annum through to the early twenty-first century. As China’s economy grew, its consumption of natural resources also increased rapidly, making China the world’s largest net importer of petroleum and other liquid fuels by 2013. In addition, labour costs, which had previously given China its cost advantage over other developing countries, rose, forcing some Chinese companies to search for lower cost production sites abroad. This culminated in the introduction of the ‘Go Global’ 走出去战略 policy in early 2000, which encouraged Chinese companies to invest abroad, acquire strategic resources, and gain a foothold in overseas markets. With its rich endowments of natural resources, a youthful population, and a desperate need for finance to meet infrastructural challenges, Africa seemed the perfect choice for Chinese companies seeking to ‘Go Global’.

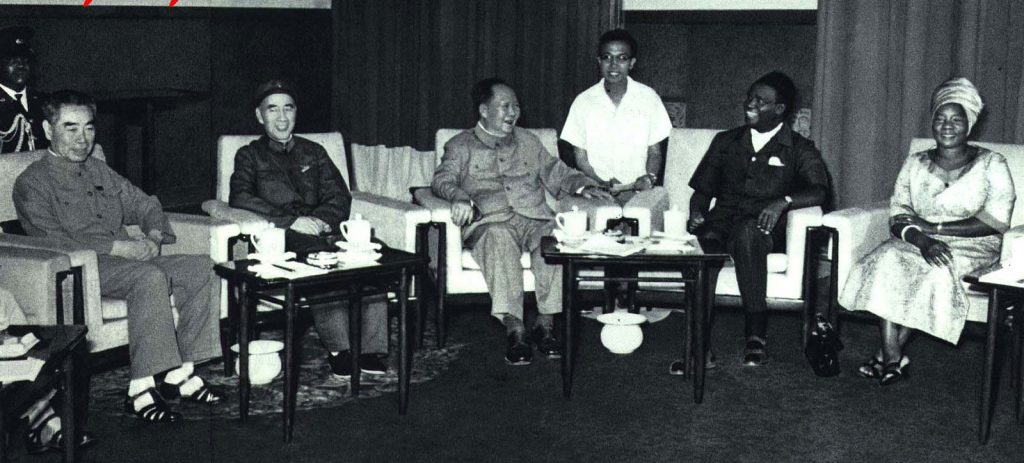

First Zambian president Kenneth Kaunda visits China in 1967. Left to right: Zhou Enlai, Lin Biao, Mao Zedong

Source: Wikiwand

In 2000, at the first FOCAC summit in Beijing, president and Party chairman Jiang Zemin 江泽民 told four African heads of states and other participants that: ‘the Chinese people and the African people both treasure independence, love peace and long for development and they are both important forces for world peace and common development’. At the third FOCAC summit in 2006, Jiang’s successor, Hu Jintao 胡锦涛, announced a raft of economic measures to achieve the ‘common interests’ outlined by Jiang, including US$15 billion for investment, industrialisation, and the construction of vital infrastructure in Africa by Chinese companies.

Xi Jinping’s speech at the 2018 Beijing summit blended the ‘common interest’ narrative with the usual monetary incentives. He spoke of a long history and a ‘shared future’ between the 1.3 billion Chinese and 1.2 billion Africans, stating: ‘We respect Africa, love Africa, and support Africa’. With so much benevolence, what could possibly go wrong?

The ‘China of Africa’: Chinese Capital and Ethiopian Economic Revival

In 1991, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) overthrew the Communist regime led by Mengistu Haile Mariam. The leader of EPRDF, Meles Zenawi, promoted a market-oriented economy; enacted new labour, industrial, and investment laws; and liberalised Ethiopia’s currency exchange regime. Zenawi’s goal was to transform Ethiopia’s agrarian economy into an industrial one. Ethiopia’s per capita GDP was just US$390 in 1991 — making it one of the poorest countries in the world at that time. The Ethiopian government followed China’s lead in making the state a key player in the country’s economy, while also relying on foreign direct investment as a source of capital and expertise.

In October 1995, facing criticism from the west over the EPRDF’s authoritarian, anti-democratic policies, Meles Zenawi visited China ‘to learn from China’s practice of market-led socialism and agricultural development’. Jiang Zemin reciprocated with a visit in May 1996. While Ethiopia was looking for capital, China sought diplomatic support and access to emerging African markets. Ai Ping 戴平, Chinese ambassador to Ethiopia from 2001–2004, noted in 2005 that: ‘[Ethiopia] plays a very unique and important role in both the sub-region [the Horn of Africa] and the continent as a whole’. Ethiopia also hosts the headquarters of the African Union, which plays a strategic role in African economic and foreign policy. Meles Zenawi said in 2006 at the FOCAC summit in Beijing, that contrary to Western media views of China in Africa as ‘The Looting Machine.’ ‘China is not looting Africa … [and the] Chinese transformation disproved the pessimistic attitude that ‘if you are poor once, you are likely to be poor forever’.

With Western democracies hesitant to invest in an increasingly authoritarian Ethiopia, Chinese firms became key players in the development of the country’s infrastructure, energy, and manufacturing. In 2006, China’s Ministry of Commerce announced a plan to build six economic zones in five African countries. Qiyuan, a privately owned Chinese steel-manufacturing company, expressed interest in building an SEZ in Dukem, Oromia state, thirty kilometres from Addis Ababa.

Despite financial challenges during its early years, the Eastern Industrial Zone (EIZ), as it is now called, is considered one of Ethiopia’s economic success stories. In 2011, the giant Chinese shoe-manufacturing company, Huajian, which makes shoes for international brands such as Guess, Calvin Klein, and Ivanka Trump, opened a factory in the EIZ. The company, in partnership with the China-Africa Development Fund, a private equity facility promoting Chinese investment in the continent, has promised to invest US$2 billion in Ethiopia before 2022. By 2017, according to Sherry Zhang, the General Manager of Huajian, the company was employing 4,200 Ethiopians. The EIZ is a good example of how Chinese capital can promote manufacturing in Ethiopia while allowing Chinese companies access to cheap labour and land.

China also finances key energy projects in Ethiopia. In 2006, the Ethiopian government signed a contract with Italian company Salini Impregilo to build a 1,870 megawatt hydroelectric dam. Although the African Development Bank and the World Bank denied funding for the dam in the face of protests from environmental groups, the Ethiopian government viewed the project as crucial for addressing the country’s poor electricity supply: the dam was projected to increase Ethiopia’s energy capacity by eighty-five per cent. The ICBC stepped up to provide US$400 million to complete the controversial project.

China has built several other dams in Ethiopia, including the Tekeze hydroelectric dam and the Gibe II and IV dams. Because of these and other investments, Ethiopia is now a net electricity exporter, with the cheapest electricity supply prices in sub-Saharan Africa. The country will earn US$250 million from electricity exports in 2019 — a figure projected to reach US$1 billion by 2023.

At the same time, these investments have exacerbated Ethiopia’s debt problems. China has reportedly lent over US$14.1 billion to Ethiopia since 2000.29 In early 2018, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) raised Ethiopia’s debt distress level to ‘high’. In September 2018, reporters at Reuters quoted the Chinese mission to the African Union in Addis Ababa: ‘The intensifying repayment risks from the Ethiopian government’s debt reaching 59 per cent of GDP is worrying investors’. As the Financial Times put it in June 2018, even some Chinese diplomats in Addis Ababa agreed that China had loaned too much.

Yet Chinese capital has helped make Ethiopia one of Africa’s fastest growing economies, averaging more than eight per cent GDP growth in the last two decades, as well as a viable manufacturing hub for top foreign manufacturers. In May of 2018, Bloomberg published an article titled ‘Ethiopia Already Is the “China of Africa” ’, with the lede: ‘They share fast growth, a strong national history and a sense that the future will be great’. Unless, as the article points out, a debt crisis doesn’t destroy the economy first.

Ethiopian officials, meanwhile, continued to lavish praise on China for its contribution to the country’s development. During a meeting with Xi Jinping in Beijing in September 2018, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed called China ‘a reliable friend’ whose ‘precious assistance’ had been crucial to Ethiopia’s economic restructuring and development.

China in Zambia: Infrastructure for Resources?

Zambia gained independence from the United Kingdom in October 1964. A year later, it was among the first African countries to establish diplomatic ties with China. Seven months after that, in response to Zambia’s condemnation of the Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Ian Smith’s Rhodesian government cut Zambia’s access to the sea by blocking the Rhodesian railway line that connects Zambia to Beitbridge, South Africa, through Harare, Zimbabwe.

This led Zambia’s first president, Kenneth Kaunda, and his Tanzanian counterpart, Julius Nyerere, to welcome, in April 1967, Beijing’s offer to fund a US$405 million railway linking Zambia’s resource-rich Copperbelt to the Tanzanian seaport of Dar es Salaam. China agreed to build the 1,860km single-track line, now called the TanZam, Uhuru, or TAZARA Railway, completing the project in 1975. Chinese leaders today refer to the TAZARA as the foundation for a ‘new’ Sino-Zambian relations that put economics first.

Poor management of its copper resources by successive governments combined with fluctuations in international copper prices, however, to make the country one of the poorest in the world by the mid-eighties. In 1990, under the auspices of the World Bank and IMF, the Zambian government started privatising its loss-making state-owned copper mining companies, selling to mainly foreign multinational companies. A Chinese SOE, China Non-Ferrous Metal Mining Company (CNMC), was the first to buy a copper mine — the Chambishi Copper Smelter — under the privatisation scheme. The company bought the mine in 1998 for US$20 million through its subsidiary Non-Ferrous China Africa (NFCA).

According to China–Africa expert Christina Alves, NFCA approached the Zambian government in 2004 with the idea of building an SEZ within CNMC’s mining licence area in Chambishi. In 2006, China’s Ministry of Commerce approved NFCA’s bid to build the Zambia-China Economic & Trade Cooperation Zone — Zambia’s first Multi-Facility Economic Zone. This was also China’s first economic zone in Africa. Alves has argued: ‘The project emerged from converging interests on both sides: China’s interest in Zambia’s copper reservoirs and Lusaka’s desire to develop a manufacturing base around its mining sector’. Both Chinese and Zambian elites cite this project to support Beijing’s narrative of win-win partnerships.

In 2017, Zambia was Africa’s second-largest producer of copper, behind the Democratic Republic of Congo. Despite several Zambian governments exploring ways to diversify the country’s economy, copper still accounted for sixty-three per cent of its foreign exchange earnings as of 2017. Yet almost three out of four Zambians lived on less than US$3.20 a day. Zambia faces pressing social and economic problems, such as poor electricity supply, with the state-owned ZESCO (Zambia Electricity Supply Corporation) unable to provide full-time electricity supply to most parts of Zambia, including the capital, Lusaka.

In Zambia, as in Ethiopia, the Chinese government has stepped in to invest in energy production. In November 2015, the Zambian government initiated the construction of a 750 megawatt hydroelectric power station on the Kafue River in the southern Chikankata district, ninety kilometres from Lusaka. The Kafue Gorge Lower will become the country’s third biggest hydropower station and will cost US$2 billion at its scheduled 2019 completion. SINOZAM, the company building the hydropower station, is owned by the Chinese state-owned hydropower engineering and construction company Sinohydro. China Export-Import Bank and the ICBC will provide fifty per cent of the funding for the project through Sinohydro; ZESCO and CAD Fund are providing the rest. The Zambian government intends for the dam to help solve Zambia’s electricity problems, as well as generate foreign revenue through exports of electricity to neighbouring countries.

Notwithstanding the positive contribution Chinese capital has had on Zambia’s economy, particularly in funding vital infrastructure, critics point to a mounting debt crisis, as in Ethiopia. On 3 September 2018, while the Zambian President, Edgar Lungu, was meeting with other African heads of state and Xi Jinping at the Beijing FOCAC summit, the British newspaper Africa Confidential published a sensational story on the detrimental impact of Chinese loans on Zambia. According to the newspaper, the Zambian government spends US$500 million of the public budget financing Chinese loans at the expense of much needed social and economic development programs. The article describes Chinese loans as a ‘cunning’ device used by Beijing to indebt poor countries and gain control over their strategic assets. It claims that China has used Zambia’s debt to gain ownership of ZESCO and Zambia’s National Broadcasting Corporation.

The article reflects widespread perceptions about China in Africa. But, as Deborah Bräutigam points out so clearly in her book Will China Feed Africa?, such media stories should be taken with ‘a grain of salt’. For example, this article claimed that over seventy-four per cent of Zambia’s debt is owed to China. However, Zambia’s Minister of Finance Margaret Manakatwe, stated in response to the article that Zambia’s total foreign debt accruing to China is actually less than one-quarter of the country’s total debt, adding that ‘The Zambian Government has not offered any state-owned enterprise to any lender as collateral for any borrowing’.

In Beijing in March 2015, President Lungu told Xi Jinping that China’s ‘win-win partnership with Africa and its sincere and valuable support for Zambia’s independence as well as its economic and social development … [has] won the hearts of the [Zambian] people’. But he didn’t speak for all hearts.

Zambians are not just passive recipients of Chinese aid and investment. In 2005, after an explosion in a Chinese mine in Chambishi killed fifty-two Zambians, there were protests in 2006, and the Zambian government responded by strengthening its workplace safety and labour standards. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Zambia also step in where the government has failed. I have written in my doctoral thesis how, after unearthing evidence that NFCA and its subsidiary Chambishi Copper Smelter (as well as Western companies) were flouting Zambia’s environmental standards, environmental NGOs, Citizens for Better Environment, and the Zambia Institute for Environmental Management pushed both the Zambian government and Chinese companies to improve their environmental standards and regulations. The point is that Chinese (and other foreign) investment is certainly not always ‘win-win’ for all Zambia, but both the Zambian government and its citizens do have agency in dealing with contentious issues as they arise.

Conclusion

The massive transformation that has occurred domestically in the past four decades, combined with Beijing’s decision to ‘Go Global’ since the turn of this millennium, have made China a global financer of foreign investment and infrastructure projects. In Africa, China has built roads, railways, bridges, dams, SEZs, and the African Union Headquarters to gain access to the region’s growing markets and vast energy and other resources, as well as to cement strong cultural and diplomatic relations. But it’s not just about money. Both the journalistic and academic literature on Sino-African relations tends to overlook the appeal of China’s Africa narrative of ‘common interest’, partnership’, and ‘friendship’.

Beijing’s ability to marshal both narrative and financial resources to gain influence in Africa is yielding good results for China, at least in the case of Zambia and Ethiopia. Both Zambian and Ethiopian leaders have expressed ‘sincere gratitude’ for China’s contribution to their countries’ development.

Serious questions remain, however, about the short-term and longer term consequences of these contributions, including the burden of debt and imbalances in trade. Some Chinese companies (and Western ones as well) stand accused, too, of poor treatment of workers and lax environmental standards. Much will depend on how African governments evolve their own regulatory and legal institutions, and facilitate the agency of their citizens to address these problems. The case of Zambia gives some cause for optimism in this regard.

Notes

Xi Jinping, ‘Full text of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s speech at opening ceremony of 2018 FOCAC Beijing Summit (1)’, Xinhuanet, 3 September 2018, online at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-09/03/c_137441987.htm

Irene Yuan Sun, Kartik Jayaram, and Omid Kassiri, ‘Dance of the lions and dragons: How are Africa and China engaging, and how will the partnership evolve?’, McKinsey, June 2017, online at: https://www.africa-newsroom.com/files/download/aa9f2979a3dc18e

Brendon Hong, ‘China’s Ugly Exploitation of Africa—and Africans’, The Daily Beast, 3 June 2018, online at: https://www.thedailybeast.com/chinas-ugly-exploitation-of-africaand-africans

Peter Hitchens, ‘How China has created a new slave empire in Africa’, Daily Mail, 28 September 2008, online at: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1063198/PETER-HITCHENS-How-China-created-new-slave-empire-Africa.html

Alexis Okeowo, ‘China in Africa: The New Imperialists?’, The New Yorker, 12 June 2013, online at: https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/china-in-africa-the-new-imperialists

George Yu, ‘China and the Third World’, Asian Survey, vol.17, no.11 (November 1977): 1036– 1048.

Ousman Murzik Kobo, ‘A New World Order? Africa and China’, Origins, May 2013, online at: http://origins.osu.edu/article/new-world-order-africa-and-china

Zhou Enlai, ‘Main speech by premier Zhou Enlai, head of the delegation of the people’s republic of china, distributed at the plenary session of the Asian-African conference’, Wilson Centre, 19 April 1955, online at: https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/121623

Jan S. Prybyla, ‘Communist China’s Economic Relations with Africa 1960-1964’, Asian Survey, vol.4, no.11 (November 1964): 1135–1143.

Jamie Monson, Africa’s Freedom Railway, Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009.

Julia C. Strauss, ‘The past in the present: Historical and rhetorical lineages in China’s relations with Africa’, China Quarterly, no.199 (2009): 777–795.

Lulu Gu and Robert Reed, ‘Chinese Overseas M&A Performance and the Go Global Policy’, Working Papers in Economics, 11/37, Christchurch: University of Canterbury, Department of Economics and Finance, online at: https://ideas.repec.org/p/cbt/econwp/11-37.html

Jiang Zemin, ‘China and Africa-Usher in the New Century Together — Speech by President Jiang Zemin’, China.org, 12 October 2000, online at: http://www.china.org.cn/english/features/focac/183730.htm

Hu Jintao, ‘Full text of President Hu’s speech at China-Africa summit’, Xinhuanet, 4 November 2006, online at: http://www.gov.cn/misc/2006-11/04/content_432652.htm

Xi Jinping, ‘Full text of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s speech at opening ceremony of 2018 FOCAC Beijing Summit (1)’, Xinhuanet, 3 September 2018, online at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-09/03/c_137441987.htm

Edson Ziso, A Post State-Centric Analysis of China-Africa relations: Internationalisation of Chinese Capital and State-Society Relations in Ethiopia, Adelaide: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Seifudein Adem, ‘China in Ethiopia: Diplomacy and economics of Sino-optimism’, African Studies Review, vol.55, no.1 (2012): 143–160, pp.145.

Six years after Zenawi’s assertion, Tom Burgis still went ahead and titled his investigative report on Chinese companies in Africa, The Looting Machine: Warlords, Oligarchs, Corporations, Smugglers, and the Theft of Africa’s Wealth, London: HarperCollins, 2015.

Foreign Ministry of the People’s Republic of China, ‘Ethiopian PM: China not looting Africa’, 16 October 2006, online at: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/zflt/eng/jmhz/t403870.htm

Deborah Bräutigam and Tang Xiaoyang, ‘African Shenzhen: China’s special economic zones in Africa’, The Journal of Modern African Studies, vol.49, no. 1 (2011): 27–54.

Hou Liqiang, ‘One man’s dream transforms into industrial showcase’, China Daily, 17 July 2015, online at: http://africa.chinadaily.com.cn/weekly/2015-07/17/content_21309023.htm

Elissa Jobson, ‘Chinese firm steps up investment in Ethiopia with “shoe city”’, The Guardian, 30 April 2013, online at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2013/apr/30/chinese-investment-ethiopia-shoe-city

Gao Wencheng, ‘Chinese factory in Ethiopia ignites African dreams’, Xinhuanet, 31 March 2018, online at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-03/31/c_137079548.htm

‘Gibe III Hydroelectric Project’, Salini Impregilo, 17 December 2017, online at: https://ethiopia.salini-impregilo.com/en/projects/gibe-iii-hydroelectric.html

‘Catastrophic dam inaugurated today in Ethiopia’, Survival International, 17 December 2016, online at: https://www.survivalinternational.org/news/11544; ‘Letter to Industrial and Commercial Bank of China regarding to Gibe 3 project’, International Rivers, 1 June 2015, online at: https://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/letter-to-industrial-and-commercial-bank-of-china-regarding-to-gibe-3-project-9048

‘The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia’, IMF Country Report, No.18/18 (January 2018), online at: https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/CR/2018/cr1818.ashx

Deborah Bräutigam and Jyhjong Hwang, ‘Data: Chinese loans to Africa’, China Africa Research Initiative, October 2018, online at: http://www.sais-cari.org/data-chinese-loans-and-aid-to-africa/

Chris Giles and David Pilling, ‘African nations slipping into new debt crisis’, Financial Times, April 2018, online at: https://www.ft.com/content/baf01b06-4329-11e8-803a-295c97e6fd0b

Maggie Fick and Christian Shepherd, ‘Trains delayed: Ethiopia debt woes curtail China funding’, Reuters, 1 September 2018, online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-africa-ethiopia/trains-delayed-ethiopia-debt-woes-curtail-china-funding-idUSKCN1LH36W

John Anglionby and Emily Feng, ‘China scales back investment in Ethiopia’, Financial Times, 3 June 2018, online at: https://www.ft.com/content/06b69c2e-63e9-11e8-90c2-9563a0613e56

Tyler Cowen, ‘Ethiopia Already is the “China of Africa”: They share fast growth, a strong national history and a sense that the future will be great’, Bloomberg, 29 May 2018, online at: https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2018-05-29/ethiopia-already-is-the-china-of-africa

‘Xi meets Ethiopian Prime Minister’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the People’s Republic of China, 2 September 2018, online at: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1591031.shtml

John Mwanakatwe, End of Karunda Era, Lusaka: Multimedia Production, 1994.

Yang Youming, ‘Speech by H.E. Mr. Yang Youming, Chinese Ambassador to Zambia at the Fare-well Reception’, Embassy of The People’s Republic of China in Zambia, 4 April 2018, online at: http://zm.chineseembassy.org/eng/sbgx/zz/t1550458.htm

Anne-Marie Pitcher, Party Politics and Economic Reform in Africa’s Democracies, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Ching Kwan Lee, The Specter of Global China: Politics, Labor, and Foreign Investment in Africa, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Ana Cristina Alves, ‘The Zambia-China Cooperation Zone at a Crossroads: What now?’, SAIIA Policy Briefing 41, Braamfontein: South African Institute of International Affairs, December 2011.

Kelvin Chongo, ‘Mining sector key to economy’, Zambia Daily Mail, 10 July 2018, online at: http://www.daily-mail.co.zm/mining-sector-key-to-economy/

Vito Laterza and Patience Mususa, ‘Is China really to blame for Zambia’s debt problems?’, Al Jazeera, 11 October 2018, online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/china-blame-zambia-debt-problems-181009140625090.html

Jimmy Chibuye, ‘Kafue Gorge Lower: Power surplus dream’, Zambia Daily Mail, 12 October 2017, online at: http://www.daily-mail.co.zm/kafue-gorge-lower-power-surplus-dream/

‘Bonds, bills and ever bigger debts’, Africa Confidential, vol.18, no.3, 3 September 2018, online at: https://www.africa-confidential.com/article-preview/id/12424/Bonds%2c_bills_and_ever_bigger_debts

Chris Phiri, ‘Mwanakatwe sets record straight on China debt discourse’, Zambia Reports, 13 September 2018, online at: https://zambiareports.com/2018/09/13/mwanakatwe-sets-record-straight-china-debt-discourse/

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, ‘Xi Jinping Holds Talks with President Edgar Lungu of Zambia, Stressing to Cherish Traditional Friendship and Advance China-Zambia Relations’, 30 March 2015, online at: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/xjpcxbayzlt2015nnh/t1251033.shtml

Mukete Beyongo, ‘Fighting the race to the bottom’, in Ivan Franceschini, Kevin Lin and Nicholas Loubere, eds. Heart of Darkness? Questioning Chinese Labour and Investment in Africa, Made in China, July–September 2016, pp.21–24.

Mukete Beyongo, ‘China’s environmental footprint: The Zambian example’, in Jane Golley, Linda Jaivin, and Luigi Tomba, eds. China Story Yearbook 2016: Control, Canberra: ANU Press, 2017.