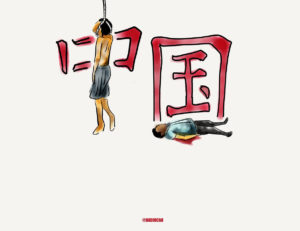

CHINA EXECUTES more people than any other nation. Yet, over the last decade, its death penalty policy has undergone a life change. This began on 1 January 2007, when the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) assumed exclusive authority for the final review and approval of all death sentences across the nation. For decades, and for most capital offences, this had been the job of provincial-level appellate courts. The number of executions that year plummeted by one third, according to the SPC, as the result of a deliberate commitment to ‘killing fewer’ 少杀 by removing the more arbitrary elements from the system.

In the early 1980s, the Party-state gave provincial courts the authority to review death penalty cases because it wanted serious crimes punished ‘severely and swiftly’. Rising crime was part of the social fallout of rapid economic growth and it was threatening social stability. So the Party ran a series of law enforcement campaigns under the rubric Strike Hard 严打. Strike Hard was both the name of intermittent campaigns and also an ongoing policy used against serious criminal offenders. Local courts responded by playing fast and loose with the death penalty. Across two decades, regardless of whether a Strike Hard campaign was in progress, the Party encouraged the liberal application of harsh punishment for crime. Over the decades, starting from Deng Xiaoping’s time, Party-state officials often quoted the adage that if a judge has the legal option to choose whether or not to apply the death penalty, that is, to choose ‘to kill or not to kill, they should choose to kill’: 可杀, 可不杀,杀.

By the end of 2003, the rationale that ‘killing many’ 多杀 deterred crime had worn thin, especially among senior police, prosecutors, and judges in Beijing. Ongoing Strike Hard campaigns had not stemmed annual rises in serious crime. More importantly, the idea of swift and severe punishment made a poor fit with Party rhetoric on the rule of law and the Harmonious Society 和谐社会 platform of Hu Jintao, China’s paramount leader from 2002–2012. Politics drives most judicial reforms in China. It was at the height of the Harmonious Society period in 2005 that Hu Jintao decided that China needed to reform the death penalty as part of his agenda for ‘harmonious justice’. The idea here was that death penalty reform would itself help to bring about a more harmonious society.

For then SPC president Xiao Yang and other reformers in the SPC, institutionalising the policy of ‘kill fewer kill cautiously’ 少杀慎杀 required offering a politically acceptable alternative to execution to provincial Party, police, and court authorities. In late 2006, Xiao Yang announced that immediate execution should be used only as a last resort, and only for the most serious or heinous crimes. He reversed the old Strike Hard adage, now saying, ‘when there is a choice to kill or not to kill, without exception, always choose not to kill’ 可杀,可不杀,一律不杀. In place of execution, the SPC encouraged the use of the suspended death penalty 死缓 for the majority of violent capital cases. In a relatively short space of time, provincial authorities came on board.

It was around this time that judicial authorities initiated a new practice called ‘criminal mediation’ 刑事调节 for death penalty cases, in which SPC judges would mediate between the offender and the victim’s family. The SPC billed it as an opportunity to enhance social harmony and mitigate social instability. It had become a common occurrence for victims’ families to protest outside the courts if convicted murderers were given a commuted death sentence instead of immediate execution. SPC judges began to strike deals: for example, an offender could pay the victim’s family hundreds of thousands of renminbi in compensation in exchange for the family’s agreement that the offender could live. The offender would then be given a suspended death sentence that would typically be downgraded to a life sentence of around eighteen to twenty years after a two-year probation period. The practice of ‘cash for clemency’ is still in operation today even though the Harmonious Society policy is long gone.

In the ten years since 1 January 2007, China’s execution rates have greatly decreased, according to the judges of the SPC. While the precise number of people executed in China each year is still a state secret, it’s estimated to be around 1,900 — an impressive drop from around an estimated 10,000 a year ten years ago.

There are two developments that could lower the number even further. One is current talk of legislating to take drug transporting off the capital punishment list. The Criminal Law, as it was amended in 1997, listed sixty-eight offences for which the death penalty could be applied, though with most, judges did not tend to favour execution. The number of capital offences in the Criminal Law has now dropped from sixty-eight to fifty-five. The four main types of crime for which immediate execution is used are murder, armed robbery with violence, drug trafficking, and the transportation of illegal drugs. Close to half the people executed today are found guilty of drug transporting: ‘mules’ caught carrying over fifty grams of methamphetamines or heroin. They tend to be poor workers from rural areas who take drugs inland from places such as the Golden Triangle border in southern China. Since drug traffickers are organised criminals who are more difficult to apprehend, policing authorities have traditionally gone after the easy-to-catch mules.

A second development is a push to improve the quality of police investigations and criminal trials. The goal is to lessen the likelihood of miscarriages of justices resulting from the longstanding if illegal practice of forced confessions. To this end, President Xi Jinping is promoting a new policy called ‘making the trial central’ to the criminal process 以审判为中心. This aims to change the tradition of ‘investigation-centered-thinking’, stressing instead the importance of rigorously testing evidence through cross-examination at trial. Reforms are currently underway to improve evidence gathering, to encourage witnesses to testify in court, and, crucially, to make unlawfully obtained evidence (like forced confessions) inadmissible at trial.

A more permanent decline in capital punishment requires much more in the way of legislative reform. Nevertheless, advocating for suspended death sentences and the other initiatives, including Xi’s policy on putting the emphasis on trials instead of investigations, are a good start.

Notes

‘China sees 30% Drop in Death Penalty’, Xinhua, 10 May 2008, online at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2008-05/10/content_6675006.htm

Susan Trevaskes, The Death Penalty in Contemporary China, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, p.36.

See also ‘The idea of “when there is a choice to kill or not to kill, always choose not to kill” “可杀可不杀的一律不杀之忧” ’, People.cn, 9 November 2006, online at: http://www.people.com.cn/GB/32306/33232/5045151.html

David Johnson, and Franklin Zimring, The Next Frontier: National Development, Political Change, and The Death Penalty in Asia, Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2009, p.277.

Amnesty International no longer publishes estimates of the number of executions in China. Duihua Human rights organisation says that around 2,400 people were executed in 2013. See: https://duihua.org/wp/?page_id=9270. See also Johnson and Zimring’s book for estimated figures in the 1990s and 2000s.