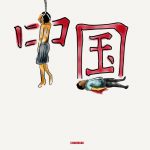

Death Penalty Reform

by Susan Trevaskes

CHINA EXECUTES more people than any other nation. Yet, over the last decade, its death penalty policy has undergone a life change. This began on 1 January 2007, when the Supreme People’s Court (SPC)1 assumed exclusive authority for the final review and approval of all death sentences across the nation. For decades, and for most capital offences, this had been the job of provincial-level appellate courts. The number of executions that year plummeted by one third, according to the SPC, as the result of a deliberate commitment to ‘killing fewer’ 少杀 by removing the more arbitrary elements from the system.