For Lijiang Old Town 丽江古城, 1 June 2016 was not a happy day. More than 800 hostels, guesthouses, and shops refused to open their doors. They had made a collective decision to protest against the local government’s insistence that they collect an eighty-yuan ‘conservation fee’ 维护费 from foreign and domestic tourists. The shop owners, mainly migrants from other parts of China, complained that the seemingly arbitrary nature of the request was hurting business. The three-day protest resulted in a dramatic decrease in tourist numbers — transforming this popular vacation spot into a ghost town.

Lijiang was not the only case of unrest in the tourist industry in 2016. On 31 May, business owners staged a similar protest in the old town of Dukezong 独克宗古城 — a Tibetan town that in 2001 successfully changed its name to Shangri-La 香格里拉 to attract tourists and investments. That these protests took place in ‘old towns’ 古城 was not a coincidence. In recent years, city and provincial governments have developed a number of ‘old towns’ to invigorate the tourism and heritage industry. Old towns, like those of Lijiang and Shangri-La, both in Yunnan province, have since become playgrounds for business investors from other Chinese cities. The resulting tensions between local authorities and shop owners reflect a long-term battle for control over profits and regulation.

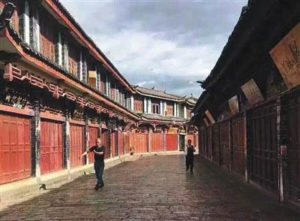

In June 2006, businesses in Lijiang Old Town closed their doors to protest against the implementation of the admission fee

Source: china.org.cn

After being listed as a World Heritage site by UNESCO in 1997, the old town of Lijiang became one of China’s most popular destinations for both international and domestic tourists. Since then, the Lijiang government has gone through a series of institutional reforms. In 2005, the government established the Lijiang Old Town Conservation and Management Bureau (LCMB). This new agency has become an exclusive authority with responsibility for heritage governance in Lijiang. According to the Regulation on the Protection of Lijiang 丽江保护条例, the LCMB is in charge of implementing the conservation law, preserving cultural relics, enhancing infrastructure and public utilities, and facilitating marketing and business development. The heritage office is authorised to impose a fine on any individual or organisation that disobeys the Regulation on the Protection of Lijiang.

As a key player in redistributing heritage resources and establishing related regulations, the local heritage agency can organise social, cultural, and economic activities without strictly following national directives. In other words, the powers and policy discretion of the LCMB means it can implement policies in its own interests. Since the central government has not categorised the old town as a scenic area or national park, according to national law, the local government should not charge an admission fee to tourists. To generate income for the conservation and development of the old town, the LCMB introduced a ‘conservation fee’ in 2001 — a local administrative charge allegedly to support heritage conservation. The conservation fee did not bother most tourists in the beginning, as there were no strict enforcement measures in place. Things have changed since July 2015, when the LCMB established more than a hundred stations in the old town to check if tourists had paid the conservation fees. This policy suddenly made waves — a number of tourists chose not to visit the old town during the daytime, as they were reluctant to pay the fees. This had driven down profits for most local businesses, eventually leading to the 2016 protest.

The confrontation was not only about profits. It is also part of a battle for power over local cultural resources between the bureaucracy and businesses. In China, governments at all levels implement top-down policies and solutions, whether or not they effectively ‘serve the people’. Decades of economic development and a flood of migrants and capital have changed the social and economic ecology of Lijiang Old Town. Local business owners, the majority of whom are from coastal areas, have started to fight the regulatory framework that they see as impinging on their freedom and profits. The conservation fee came to be regarded as symbolic of the local government’s claim over the right to regulate and speak for local interests, including culture. The questions of who should profit from and ‘own’ the culture have become the key issues in the heritage management and governance of places such as Lijiang.

Where is the local community in this picture? Most of the value added in the tourism industry tends to be appropriated by the local government and outsiders, whose wealth, education, business skills, and networks make them the predominant force in the market. In Lijiang, the Naxi people — the original residents — find it difficult to keep up with the rapid changes in the tourism-dominated environment. As a result, an increasing number of local residents rent their houses to business people and move outside the old town. Places like Lijiang easily become stereotyped ‘theme parks’ in which local communities play a marginal role, entangled in the battle between local bureaucracies and business. It is in this struggle that old towns lose the very core of their cultural value.