On 15 March, China’s National People’s Congress adopted the country’s Thirteenth Five-Year Plan 十三五规划纲要. It focuses on innovation, structural reform, environmental protection, and transitioning away from an investment-dependent growth model. Coming at a time of economic restructuring and slowing economic growth, the Plan presents the government’s vision for China’s ‘new normal’ 新状态 — which is of China as a world leader in innovation, with a ‘modestly prosperous’ society 小康社会, and a consumption-driven economy.

The Thirteenth Five-Year Plan, which covers the period from 2016–2020, sets five major objectives:

- Technological and informatisation: The Plan sets the most ambitious targets for technological development to date. Innovation takes first place in the Plan and takes up a whopping thirty-eight pages. The Plan lays out nine major initiatives, including ‘Sci-Tech Innovation 2030 — Megaprojects’ (which prioritises the development of certain technologies like new aviation engines and gas turbines, robotics in the field of manufacturing, and the development of so-called ‘advanced materials’), ‘Made in China 2025’ (focusing on upgrading manufacturing technology), and ‘Internet Plus’ (extending the use of the Internet in industry). Together these projects will attempt to make China a global innovation leader in the fields of smart manufacturing, big data, quantum telecommunications, and robotics. Notably, the Plan marks the return of ‘indigenous innovation’ 自主创新 (used six times in the Plan), an expression that had been replaced by ‘innovation-driven development’ 创新驱动发展 in 2012 to assuage fears of foreign businesses that they would be left out of China’s innovation drive. While the Plan has a long list of priority technologies the Chinese government hopes to develop, these are expressed in broad, or vague terms.

- Environment: Environment-related targets account for half of all mandatory targets. Together, they add up to the boldest outline for environment protection and tackling

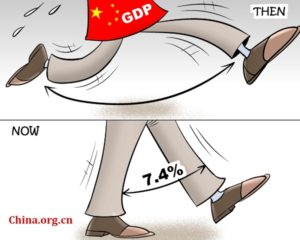

pollution in a Chinese five-year plan to date. Most notably, the Plan places quotas for cleaning-up waterways (raising the number of waterways suitable for drinking and fishing to seventy percent) and reducing PM2.5 nationwide. The Plan also sets targets for increasing the share of non-fossil fuel-based energy to fifteen percent of total supply (up from 11.4 percent). - A mid–high target for economic growth: Despite rising debt, a slowing economy, and overcapacity in many industries — and early drafts of the Plan that had scrapped growth targets altogether — economic growth remains an important priority, reflected in the Plan’s growth target of 6.5 percent. The Plan acknowledges that achieving 6.5 percent growth will require tapping into new engines of growth and efficiency. It is also the first Plan to include an annual target for labour productivity, which is to increase by 6.6 percent per year.

- Institutional reform: One way in which the Plan will attempt to unleash greater productivity is through expanding market-oriented reform. This includes reforming interest rates and the securities market in favour of the free market, simplifying regulatory codes, easing access to credit, and so on. Unsurprisingly, the Plan outlines a major push to reform state-owned enterprises (SOEs), a centrepiece of Xi’s economic reform as SOE debt and the enterprises’ collective burden on the economy spirals out of control. Meaningful reform requires making SOEs more self-sufficient and responsive to market forces. Many experts doubt Beijing will be successful, because of the political complexity of this issue, which relates to longstanding ideological assumptions about the structure of the Chinese economy post-1949.

- Poverty reduction: One of the few non-environment related mandatory quotas in the Plan is for poverty reduction. Building on the momentum of the Twelfth Five-Year Plan the government intends to raise 55.75 million people out of poverty by 2020. The Chinese government defines rural poverty as living on less than 2,300 renminbi a year (or 6.3 renminbi per day). That is still less than the World’s Bank’s global poverty standard of US$1.25 a day.

Notes

‘During the period of the “thirteenth five-year plan” fifteen major technology projects will be implemented by 2030 “十三五”期间实施面向2030年15个重大科技项目’, Xinhuanet, 22 July 2016, online at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-07/22/content_5093765.htm

‘Outline of the thirteenth five-year plan (full text) 十三五规划纲要(全文)’, Xinhuanet, 19 March 2016, online at: http://www.sh.xinhuanet.com/2016-03/18/c_135200400.htm

Scott Kennedy and Christopher K. Johnson, ‘Perfecting China, Inc. — The 13th Five Year Plan’, Center for Strategic International Studies, Washington DC, 2016, online at: https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/160521_Kennedy_PerfectingChinaInc_Web.pdf

‘Can China wipe out poverty by 2020?’, Forbes, 19 August 2016, online at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/sarahsu/2016/08/19/china-wipes-out-poverty/#c62d282461b6