On 16 January 2016, voters in Taiwan elected their first female president, Tsai Ing-wen 蔡英文, and gave the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) an absolute majority in the Legislative Yuan, Taiwan’s parliament, for the first time. The election results were a thorough repudiation of the ruling party, the KMT, and Taiwan’s outgoing president, Ma Ying-jeou 馬英九.

Under President Ma, who headed Taiwan’s government from 2008 to 2016, Taiwan had forged closer ties with mainland China. The government had delivered a series of cross-Strait agreements on trade, tourism, education, and investment. Cross-Strait trade and investment grew rapidly through his presidential terms, and several million mainland tourists began visiting Taiwan every year. Under Ma, there were reg-ular high-level meetings by government officials from each side as part of a policy to institutionalise cross-Strait relations.

In Singapore in November 2015, Ma and Xi Jinping held the first-ever meeting between the leaders of the Republic of China and the People’s Republic of China. For Ma, this historic gesture was the high point of his presidency. However, for many Taiwanese voters, the meeting was the culmination of a period of disenchantment and anger.

Long before the historic summit and the presidential election campaign, a new generation of political activists had begun arguing that cross-Strait trade and exchanges benefitted ordinary people in Taiwan far less than they did the KMT’s own crony networks of political and business interests. As discussed in the 2014 Yearbook, the Anti-Media Monopoly Movement, which began in mid-2012 and gained momentum in the second half of that year, campaigned successfully against the concentration of media ownership in Taiwan in the hands of the pro-Chinese businessperson Tsai Eng-meng 蔡衍明.

In 2014, student activists of the Sunflower Movement occupied the Legislative Yuan to protest against a bilateral agreement that would have given Chinese commercial interests access to key areas of Taiwan’s economy including the media, banking, and education. The protesters claimed that the agreement would have afforded mainland China undue influence over Taiwan’s social and cultural life and that this would ultimately undermine Taiwan’s democratic system and freedoms.

The results of county and municipal elections in November 2014 showed that the concerns expressed by the student activists were widely shared. The KMT lost the mayorships of every major city bar one, and following that election the entire cabinet of the Taiwanese government resigned. The KMT’s heavy defeats not only bestowed formal democratic legitimacy on the position of anti-KMT activists but also enabled the DPP to capitalise on voter sentiment to build an unstoppable momentum through 2015.

Students mobilised again in July 2015 to protest changes to high school history textbooks proposed by the Ministry of Education. The protesters were angered by changes to the language and terminology with which the textbooks discussed key events in Taiwan’s history, such as the period of Japanese colonial rule (1895–1945). They said that these changes both over-emphasised Taiwan’s Chinese identity and reintroduced the style of education that characterised Taiwanese education in the authoritarian era of Chiang Kai-shek and his immediate successors (1949–1987).

During the campaign for the 2016 presidential election, the KMT presidential candidate Eric Chu 朱立倫, the chairman of the KMT, placed Taiwan’s relationship with mainland China at the centre of his presidential campaign. Chu said that the KMT had created a stable basis for Taiwan’s relationship with the Mainland, which, he argued, afforded Taiwan the best prospects for long-term prosperity and peace.

Tsai Ing-wen conversely emphasised the DPP’s focus on domestic issues, noting in particular the poor state of Taiwan’s economy, wage stagnation, and housing affordability. She also called for better environmental protection and a culture of innovation. She attacked the KMT for its ineffective domestic governance, using examples such as the tainted cooking oil scandal in late 2014, in which food company Chang Guann 強冠企業 was found to have adulterated cooking oil with recycled oil and other substitutes.

Tsai avoided, as much as possible, being drawn into a clear position on Taiwan’s relations with mainland China. Rather, she stressed that Taiwan has a unique identity and called for stability and continuity in cross-Straits relations. She pledged to manage cross-Strait relations in accordance with the Constitution of the Republic of China and thereby accommodating a key demand from Beijing. At the same time, her emphasis on domestic issues of deep concern to voters implicitly criticised the KMT’s approach to relations with China as well as the notion advanced by the KMT that closer links to the Mainland represented a positive future for Taiwan.

Taiwan’s economy slipped into recession in late 2015 as campaigning for the presidential election reached fever pitch. Party figures on both sides threw inflammatory statements and slurs against their opponents. Senior KMT figure Chiu Yi 邱毅 accused Tsai Ing-wen of illegally profitting from a real estate deal in the 1990s. The DPP responded by publicising Chiu Yi’s extensive land holdings and financial interests. The election rallies grew ever larger and were as deafening as rock concerts. The campaigning received non-stop and frequently emotive and hyperbolic coverage from Taiwan’s twenty-four-hour cable news media.

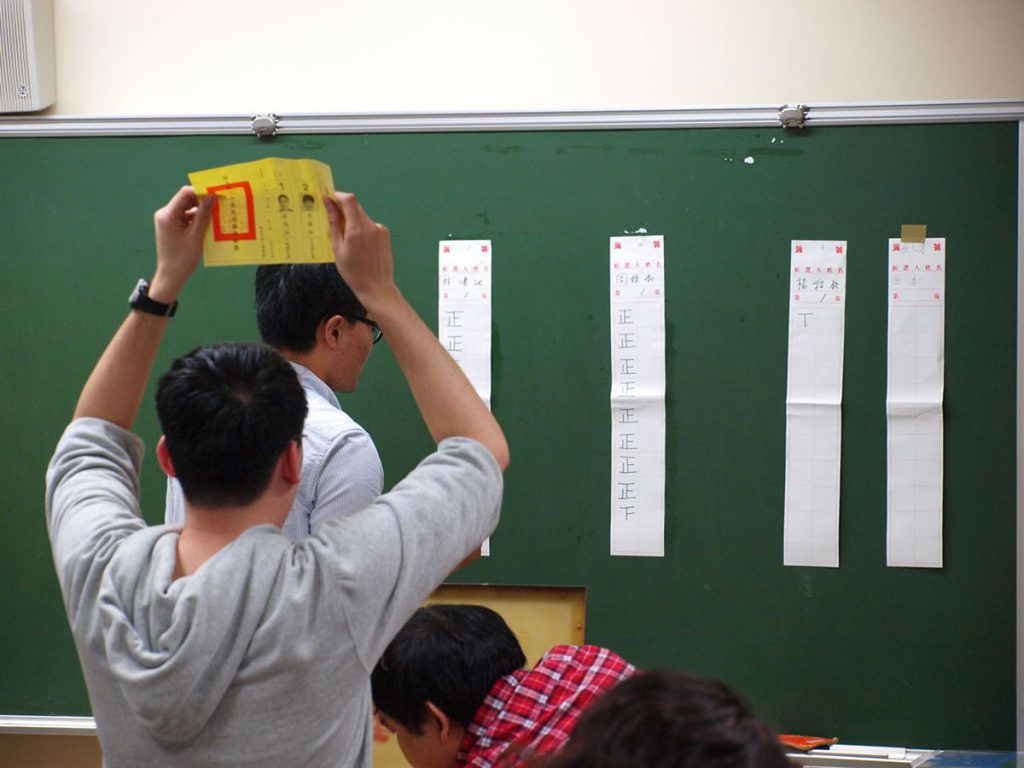

When election day dawned, Taiwanese citizens cast their votes and at the end of the day the process of vote counting began. In contrast to the raucousness of campaigning, vote counting at the end of an election day in Taiwan is a solemn and formal process. School classrooms commonly serve as polling stations, with local teachers acting as tellers and counters. When the voting concludes, the large yellow ballot boxes, emblazoned with the flag of the Republic of China, are unlocked, their broad paper seals torn, and a teller pulls out the large voting slips one at a time. A second holds it aloft in both hands and calls out the voter’s choice. At the blackboard, a third repeats the result and records it as a line on the long strip of paper dedicated to that candidate, each five lines forming the complete character zheng 正. This style of counting is widely used in shops and restaurants across the Chinese-speaking world but zheng, which means correct, exact or orthodox, acquires a special importance in this context. A fourth counter takes the ballot paper, checks it off, and stacks it.

At the other end of the classroom, representatives of the political parties and Central Election Commission officials watch carefully. If there is a miscount, a shout goes up and the process stops. The ballot paper is examined and an election official notes the error. Local police are on hand, and sometimes individuals and families known to the scrutineers will wander into the classroom to observe the process. When all the votes are counted, the scrutineers examine the empty ballot boxes and the final tally is made. The election officials then phone in the results to the main election tally room of the Central Election Commission in Taipei. The CEC takes over a large hall on the Taiwan Police College campus, where hundreds of journalists, politicians, and observers gather to watch huge screens broadcasting the results.

The counting of the votes in Taiwan has the quality of a rite. The practice of counting becomes a series of formalised repeated motions as the ballot papers are passed between the tellers, while the uttered declarations of the ballots are like a secular liturgy of versicle and response.

In the Chinese worldview, rites, or li 禮 are a central part of the many lineages of thought and practice that make up the Chinese world, including Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. The classical Confucian text the Li Ji 禮記 or Book of Rites, one of the Five Classics of the Confucian canon, prescribes ritual practices and describes their moral, social, and political value.

Rites are one of the ways political power, the social order, morality, and cosmology are understood as all interconnected. They establish the social regulation of behaviour as the foundation of power and order. Through rites, an individual knows the correct behaviour for their place and time in society. In that knowledge, he or she is able to see beyond the disorder of everyday life to a higher and enduring social order. Rites, with their requisite seriousness and forbearance, afford participants an experience of things being put right and in this momentary symbolic rectification of everyday deviations people can entertain the prospect of an ideal, or even orthodox and transcendent social order.

For the Taiwanese, the ritualised way in which their votes are counted, with every one of twelve million ballot papers held aloft and declared out loud, is an enduring expression of social and political ideals that they continue to observe above the noise of party politics and vociferous political activism. The public declaration of the political will of each individual member of Taiwanese society is intrinsic to how the Taiwanese have come to understand democracy as an orthodox social and political order.

In 2016, after the counting of the votes delivered victory to Tsai and the DPP, their supporters were jubilant and tearful. The KMT’s Eric Chu bowed grim-faced after conceding defeat. In her victory speech, Tsai said: ‘the people want to see a government more willing to listen to the people, a government that is more transparent and accountable, and a government that is more capable of leading us past our current challenges and taking care of those in need.’

But Tsai and the DPP face a contracting economy and a belligerent Beijing. One of her greatest challenges may be to manage expectations within her party and among young student activists as she makes the inevitable compromises of governance. There is nothing to suggest that the Tsai era will be less rancorous than the Ma era. However, just as Taiwan’s body politic judged the KMT unfit to rule on election day in 2016, in four years Tsai Ing-wen and the DPP will face a similar ritual when the Taiwanese voters renew their commitment to their democratic system.

Huang An’s Witch Hunt for Taiwanese Independence Supporters

by Lorand Laskai

In the lead-up to the Taiwanese presidential election, the fifty-four-year old Taiwanese singer Huang An 黄安 (best known for his 1993 pop hit New Dream for a Pair of Butterflies 新鸳鸯蝴蝶梦) launched a personal campaign to expose supporters of Taiwanese independence 台独份, particularly in Taiwan’s entertainment industry, and report them 举报 over Weibo to Chinese authorities. Huang An’s music career initially took off in Taiwan, where he was born. Yet like many Taiwanese artists, he found a far larger market for his work on the Mainland. Unlike a number of other Taiwanese artists and entertainers who perform in mainland China and make a conscious decision to underplay any personal politics that would be controversial there—pro-independence views, for example—Huang sings in harmony with the Communist Party’s adamant opposition to Taiwanese independence.

Huang’s one-man Weibo campaign started in earnest in late September 2015, when Chung Yu-chen 钟屿晨, a politically-minded twenty-four-year-old Taiwanese businesswoman, posted a status update on her Facebook page after returning from a business trip to the Mainland. In it, she joked about taking mainlanders’ money and using it to strengthen the cause of independence. Prickly Chinese netizens expressed anger, but Huang went a step further. The singer dredged up and posted information about Chung’s company and the Xiamen-based state-owned enterprise with which it was co-operating, and tagged relevant government agencies on Weibo. Soon after, Huang posted a picture of himself outside the gate of Beijing’s Taiwan Affairs Office 国台办 holding up a sign with the words ‘I am anti-Taiwanese independence, not anti-Taiwan’ 我是反台独,不是反台湾 scrawled across it.

On 20 November, Huang reported on Taiwanese singer Crowd Lu 卢广仲, divulging online that the artist, who had been slated to perform at a music festival in Dongguan, had joined the opposition to a controversial service trade agreement with China in 2014. Huang explained that he had originally withheld this information lest he ruin the young artist’s career, but had changed his mind: ‘I have only one reason for reporting you [to the authorities]: Taiwanese Independence! Crowd Lu, my little friend, why force yourself to go sell your voice in a place you oppose, protest against, disdain and raise your voice against for “suppressing Taiwan’s nationhood?” ’ 我举报他的理由只有一条:台独!广仲小朋友,何必勉强自己去你反对、抗议、不屑、呛声、‘打压台湾国’的地方卖声呢? The artist dropped out of the music festival and has not toured in the Mainland since.

A profile of Huang published around the same time reported that he had become ‘obsessed’ with the ‘report’ function on his Weibo and spent all his time ‘before sleep, on the road, and even on the toilet’ trawling Weibo for signs of Taiwanese independence sympathizers. Once, in the span of a few minutes, Huang reported five people and received a system error notification: ‘your reports exceed normal frequency, please wait five minutes then try again.’

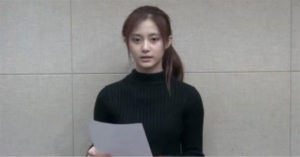

Huang An’s next two high-profile targets were TV host and comedian NONO 陳宣裕 and pop singer Chou Tzu-Yu 周子瑜. NONO, apparently an old friend of Huang, provoked Huang’s anger after he voiced his support for an independence-leaning legislative candidate in his hometown. Huang reported NONO and the comedian cancelled an upcoming TV appearance in the mainland. Chou Tzu-Yu unwittingly entered Huang’s sights after she held up a Taiwanese flag during a performance with her international K-pop group TWICE on South Korean television. Huang railed against the sixteen-year-old singer on Weibo, and called for a boycott of her music, leading a series of mainland TV programs and venues to cancel performances.

With Chou, Huang An finally seemed to go too far. On 15 January 2016, the eve of the Taiwanese election, Chou’s talent agency released a video of the young singer reading a scripted apology. ‘There is only one China … and I am proud to consider myself thoroughly Chinese,’ the teary-eyed singer said. Taiwanese society reacted with disgust: legislators called for an inquiry into revoking Huang’s Taiwanese citizenship and KTV parlors on the island boycotted his music. Observers have ascribed the large voter turnout for independence-leaning candidates on election day in part to the outrage over Chou’s forced apology.