The top result on a Google search for ‘Internet pollution’ in English is an article on Wikipedia about ‘information pollution,’ which is defined as ‘the contamination of information supply with irrelevant, redundant, unsolicited and low-value information’. The rest of the top Google results concern the carbon emissions caused by the electricity used by Internet servers and environmental degradation caused by electronic waste.

Internet pollution: in this cartoon a computer is pouring vulgar words into the head of the user

Image: img5.imgtn.bdimg.com

Chinese language searches for ‘Internet pollution’ 网络污染 on Baidu 百度, China’s leading search engine, as well as on Google, present a slightly different definition. The top result on both is a long page on Baidu’s own Baike 百科 (a kind of commercial Wikipedia) that notes the following: ‘For most Internet users these days, many Chinese websites have more and more “Internet pollution” that, like psoriasis, causes endless annoyance.’

The Baike entry then notes that because the Internet and mobile networks are developing so rapidly, governments are always playing catch up with their regulation. Before describing the Chinese situation or even defining what exactly Internet pollution means, it provides a list of Internet ‘management’ strategies used in the USA, UK, South Korea, Japan, and France, followed by several paragraphs on Chinese government measures to control the Internet. The entry quotes from a 2010 speech by Liu Zhengrong 刘正荣, then deputy director of the State Council Information Office Internet Bureau (one of the organisations responsible at that time for online ‘public opinion guidance’, aka propaganda) on the need for government regulation and management to continuously keep up with the rapid development of the Internet.

The article says the problems of Internet pollution include threats to national security, pornography, the spread of rumors, and the ‘malicious spread of harmful information’ 恶意传播有害信息, fraud, privacy infringement, dating scams, and ‘Internet violence’ 网络暴力, which is probably best rendered in English as cyberbullying.

All of this is of a piece with a strategy that is old as the Chinese Internet itself. In 1997, when only a few hundred thousand people were online in China, Geremie Barmé and Sang Ye published an article in Wired magazine titled ‘The Great Firewall’. It was the first published use of the now common phrase that describes the cordon sanitaire that Chinese censors have erected to block Chinese Internet users from accessing, inter alia, all major international social media services and many foreign news sites. Barmé and Sang described early work on what Chinese Internet users now refer to by the abbreviation GFW:

In an equipment-crowded office in the Air Force Guesthouse on Beijing’s Third Ring Road sits the man in charge of computer and Net surveillance at the Public Security Bureau. The PSB—leizi, or ‘thunder makers,’ in local dialect—covers not only robberies and murder, but also cultural espionage, ‘spiritual pollutants,’ and all manner of dissent. Its new concern is Internet malfeasance.

A computer engineer in his late 30s, Comrade X (he asked not to be identified because of his less-than-polite comments about some Chinese ISPs) is overseeing efforts to build a digital equivalent to China’s Great Wall. Under construction since last year, what’s officially known as the ‘firewall’ is designed to keep Chinese cyberspace free of pollutants of all sorts, by the simple means of requiring ISPs to block access to ‘problem’ sites abroad.

State rhetoric about purifying the Internet intensified in 2012, the year that Chinese social media’s ability to challenge the official narrative was probably at its lowest point to date. Calls to cleanse the Internet of ‘poisons’ and ‘pollutants’ have grown increasingly shrill every year, as documented in every edition of the China Story Yearbook since then. As mentioned in the China Story Yearbook 2014, a report published in February that year quoted Xi Jinping as saying that cyberspace should be made ‘clean and chipper’ (in the Xinhua News Agency’s translation). Elsewhere Xi has called cyberspace an ‘ecology’ 生态 that should be developed in the image of ‘crystal-clear water and lush mountains as an invaluable asset’ 绿水青山就是金银山. To purify the ecological system, authorities run campaigns like the ‘Clean Internet 2015’, which closed down tens of thousands of websites featuring allegedly pornographic and obscene content. The rhetoric is accompanied by offline crackdowns, including arrests, the shutting down of Internet services, and police investigations. The year 2015 was no exception. But if official statements focus on clamping down on crime, including the dissemination of pornography, official actions often aim at the censorship of political ideas and restricting independent political activities.

For several weeks in January 2015, the technicians of the Great Firewall interfered with VPNs, or Virtual Private Networks, popular tools for getting around the obstructions to browsing foreign sites. Most VPN services were throttled to the point of being unusable. VPNs are not illegal per se—but Chinese law requires companies and individuals using them to register with the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. In July, a draft Cybersecurity Law was published that made a range of Internet-based activities illegal and required tech companies operating in China, if asked, to provide law enforcement with technical assistance, including decryption of user data. The final version of the law went into force on 1 January 2016.

In August 2015, meanwhile, the Ministry of Public Security announced the ‘punishment’ of at least 197 people for ‘spreading rumours’ online and said they had shut down 165 ‘online accounts’. The ‘rumours’ were related to China’s stock market travails, the explosions at the port in Tianjin and the military parade to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. In December, the activist lawyer Pu Zhiqiang 浦志强 went on trial in Beijing for his online social commentary; the Second Intermediate Court of Beijing found him guilty of ‘picking quarrels and inciting ethnic hatred’, and gave him a suspended three-year prison sentence.

The Communist Party under Xi Jinping sees free expression and political organising on digital platforms within China as a threat. It is also wary about foreign countries, particularly the US, using the Internet both to undermine the Party ideologically and for espionage and cyber-warfare. Edward Snowden’s 2013 revelations about the global surveillance activities of the American National Security Agency (NSA) changed the conversation about Internet security and technology controls in China almost overnight. The Snowden revelations provided compelling proof of the American intentions that Chinese Internet regulators had long warned about. It became much tougher for Google to claim no political agenda and for the US State Department to reassure countries like Russia and China of its good intentions.

The Snowden Papers were hardly the first revelations to alarm China about the potential harm of the global Internet. In June 2012, The New York Times published an article claiming that the malicious computer worm Stuxnet was a jointly built US-Israeli cyber-weapon designed to sabotage the Iranian nuclear program. Previously, American social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter had been widely heralded as major factors in the Arab Spring protests of 2010–2012—leading to Adam Segal, author of The Hacked World Order, calling the period (from June 2012 to June 2013) ‘Year Zero’ of the dramatic reassertion of national controls over cyberspace. Of all the states and ruling parties, China was perhaps the most concerned and best prepared for this project.

In 2014, the Party-state established the Central Leading Group for Internet Security and Informatisation 中央网络安全和信息化领导小组 with, significantly, Xi Jinping himself at its head. One of the members of the leading group was Lu Wei 鲁炜, who became Xi’s able lieutenant as the head of the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) 中央网信办, also established in 2014 to centrally manage Internet censorship and control. The CAC took over the functions of the State Council Information Office Internet Bureau (for more on this subject see the China Story Yearbook 2014, Chapter 3 ‘The Chinese Internet ‘Unshared Destiny’, pp.106–123).

The CAC has some elements in common with a dynamic Internet start-up. The average age of its staff (37.8 years old) is young, at least by the standards of a Chinese government agency, and CAC officials are known to work long hours thanks to the organisation’s quickly expanding mandate. Within two years of its founding, the CAC has taken a central role in implementing Xi’s vision of the Internet, giving Lu Wei a prominent media profile. A key part of this vision is the concept of Internet sovereignty, which emphasises the authority of a nation-state to regulate cyberspace in its own unique way.

By the time Xi Jinping made his state visit to the United States in September 2015, with Lu Wei in his delegation, he was well prepared to meet the Obama government’s criticisms about alleged Chinese hacking of US government and commercial websites with vague promises of co-operation on cybersecurity issues.

His confidence was due in no small part to China’s huge, dynamic and expanding Internet community. At the end of 2015, the country’s population of Internet users had grown to around 700 million. China is the only country whose Internet companies can rival the titans of Silicon Valley, whether measured by user numbers, scale or revenues.

Alibaba was originally an ecommerce company offering services similar to Amazon and Ebay. It used some of the US$25 billion war chest generated by its September 2014 listing on the New York Stock Exchange to rapidly expand into a huge variety of new businesses from consumer credit and mobile payments to film production. In 2015, the search engine Baidu grew a mobile phone- and online-based food delivery service from nothing to a business reportedly worth RMB 8 billion (US$1.2 billion). By the end of 2015, Tencent’s WeChat mobile messaging service had more than a billion accounts with users active each month totalling nearly 700 million. The service offers a combination of messaging (similar to WhatsApp), mobile payments, flight and train ticket booking, car hailing, Facebook-type social media feeds, and many other apps and services. WeChat is perhaps the first Chinese Internet or mobile product that has a real international presence: one out of every four users is non-Chinese. Facebook and other Silicon Valley companies are studying it as a potential model for future development. Didi Dache, a car-hailing app (renamed Didi Chuxing in early 2016 after a merger with a rival), is the world’s largest company of its kind and the only serious global rival to Uber. In 2015, Xiaomi, an upstart Chinese company founded in 2011, became the world’s fifth largest smartphone maker, selling 70.8 million units.

It is not only giant companies that are powering the dynamism of the Chinese Internet and its broader economy: in November 2015, Bloomberg reported that China was a world leader in entrepreneurship, ‘spawning 4,000 new businesses a day’. Many of these are tech companies, including everything from one person boutiques selling handmade dresses on Alibaba’s Taoabao platform to companies like HaoBTC, a Bitcoin mining firm with servers in the mountains of west Sichuan that give them access to cheap hydroelectric power.

All this means that the government can laugh off criticism that government censorship and regulation of the technology industry hampers innovation and prevents China’s Internet companies from achieving global significance.

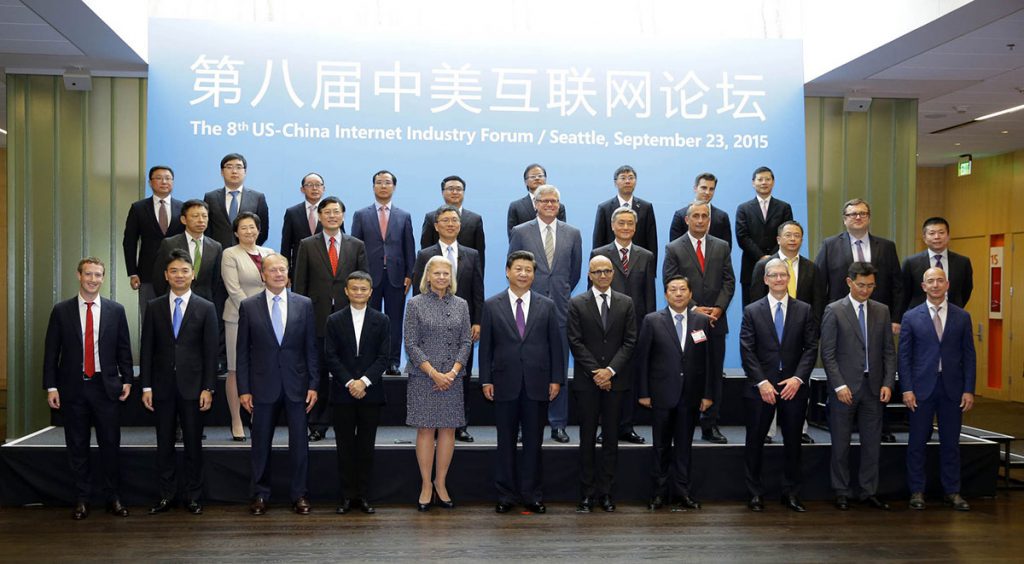

During Xi’s 2015 state visit to the US, he visited the Microsoft headquarters in Redmond, where he and Lu Wei posed for a photograph with the grinning CEOs of Apple, Facebook, IBM, Cisco, Amazon, Intel, and Airbnb. Despite the fact that many of these companies are blocked from operating in China or subject to protectionist regulations, none of their executives could resist a meet and greet with the Chairman of Everything and his head cyberspace administrator.

Conference Call

CAC organised the Second Annual World Internet Conference (also known as the Wuzhen Summit) held in mid-December 2015 in the river town of Wuzhen in Zhejiang province. Some wags on the Chinese Internet dubbed the conference the ‘Third World Internet Conference’ because with the exception of Russia, Iran and South Korea, there were no government representatives from major countries in attendance, with officials from countries such as Tonga, Congo, and Guinea making up the bulk of the twenty-one state participants.

Nonetheless, Chinese media reported that the event attracted more than 2,000 Internet professionals, officials, and experts from more than 120 countries and regions. Guests included Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, Alibaba founder Jack Ma, the CEOs of Airbnb and Netflix, as well as high-level representatives from Facebook, Google, and LinkedIn, Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales, and Fadi Chehadé, the president of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), an organisation that sets standards for top-level domains and root servers that ensure that you are directed to the correct page when you type a web address into a browser.

The principal purpose behind the annual conference, according to Xinhua, is ‘to promote the Chinese Communist Party’s vision of Internet governance 互联整理 to an international audience and to gain allies against the perceived Western encroachment upon China’s cyber sovereignty 互联主权. At the first Wuzhen Summit in 2014, attendees woke up to find a draft joint statement affirming China’s concept of ‘Internet sovereignty’ that had been slid under their hotel doors on the final night. Participants were encouraged to sign it. But the overture did not succeed—the first Wuzhen Summit ended without a communiqué, and the CAC scuttled whatever goodwill the three-day conference had managed to cultivate among those participants and observers sceptical of China’s online censorship regime.

At the Second World Internet Conference the pitch was more compelling and the staging more graceful. Whereas Xi Jinping merely sent a video message in 2014, in 2015 he was in attendance and delivered a keynote speech. He outlined ‘four principles’ 四项原则 and made ‘five propositions’ 五点主张 for international Internet governance, centring on the idea of ‘respecting Internet sovereignty’ 尊重网络主权.

China enjoyed a propaganda coup with cameras trained on the Silicon Valley executives listening to China’s vision for a clean and regulated cyberspace. And the Chinese government scored a significant victory at the end of the conference when ICANN president Chehadé accepted the role of co-chair of the Wuzhen Summit’s high-level advisory committee.

Only days before the conference, the UN had approved a document titled ‘Ten-Year Review of the World Summit on the Information Society’, which sets out the processes for how the Internet is governed. The final text substituted, at China’s insistence, the word ‘multilateral’ for ‘multi-stakeholder’. The latter includes non-government agencies—civil society, in effect—in the discussion of how to manage the global Internet, whereas ‘multilateral’ grants governments a privileged role and the prerogative to manage their own cyberspaces independently. This was a victory for the Chinese concept of ‘Internet sovereignty’, for it grants Chinese and other governments fed up with the pesky inconveniences of an open Internet the moral right to ‘purify’ and enclose their own cyberspaces. The Chinese government has not yet figured out how to rid the air and soil of pollution, but it is doing a remarkable job of cleansing its Internet from unwanted impurities.

Afterword: ‘Twas ever thus

The 1997 Geremie R. Barmé and Sang Ye article mentioned above quotes Xia Hong, then public relations manager for a company called China InfoHighway Space:

The Internet has been an important technical innovator, but we need to add another element, and that is control. The new generation of information superhighway needs a traffic control centre. It needs highway patrols; users will require driving licenses. These are the basic requirements for any controlled environment.

All Net users must conscientiously abide by government laws and regulations. If Net users wish to enter or leave a national boundary they must, by necessity, go through customs and immigration. They will not be allowed to take state secrets out, nor will they be permitted to bring harmful information in.

As we stand on the cusp of the new century, we need to—and are justified in wanting to—challenge America’s dominant position. Cutting-edge Western technology and the most ancient Eastern culture will be combined to create the basis for dialog in the coming century. In the twenty-first century, the boundaries will be redrawn. The world is no longer the spiritual colony of America.

Notes

Kai Ge 开可 and Yang Yue 杨月, ‘习近平提五大理念统领网信领域,指点中国“第五疆域”建设’, The Paper, 22 April 2016, online at: http://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1459594_1

‘学者热议:李克强提的“互联网+”是个啥概念?’, people.cn, 5 March 2015, online at: http://scitech.people.com.cn/n/2015/0305/c1007-26644489.html

Taylor Hall, ‘China Outstrips Rest of the World in Creating Startups, Report Shows’, Bloomberg, 23 November 2015, online at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-11-23/china-outstrips-rest-of-the-world-in-creating-startups-report-shows

Geremie R. Barmé and Sang Ye, ‘The Great Firewall of China’ Wired, 6 January 1997, online at: http://www.wired.com/1997/06/china-3/

‘公安部整治网络谣言 查造谣197人关停网络账号165个’, chinanews.com, 31 August 2015, online at:

http://www.chinanews.com/gn/2015/08-31/7497232.shtml

‘网信办工作日常曝光,国考季写给师弟师妹的一封信’, Weixin, 18 October 2015, online at: http://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzA5OTA2OTU5Mg==&mid=400053976&idx=1&sn=4d15c2e4dcbcde2de

b546e6ada4eb301&3rd=MzA3MDU4NTYzMw==&scene=6#rd

Custer, ‘Baidu’s food delivery service Waimai looking to raise $500m: report’, Tech in Asia, 30 December 2015, online at: https://www.techinasia.com/report-baidus-o2o-food-delivery-service-waimai-raise-us500m

Steven Millward, ‘WeChat still unstoppable, grows to 697m active users’, Tech in Asia, 17 March 2016, online at: https://www.techinasia.com/wechat-697-million-monthly-active-users

Bitcoin Forum ‘Three months living in a multi-petahash BTC mine in Kangding, Sichuan, China’, online at: https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=1072474.0

Wuzhen Summit website: http://www.wicwuzhen.cn/

‘方可成:“外交”是中国举办“世界互联网大会”的本质’, Initium Media, 18 December 2015, online at: https://theinitium.com/article/20151218-opinion-world-internet-conference-foreign-policy-fangkecheng/

James T. Areddy, ‘China Delivers Midnight Internet Declaration — Offline’, The Wall Street Journal, 21 November 2014, online at: http://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2014/11/21/china-delivers-midnight-internet-declaration-offline/