XI JINPING AND THE PARTY leadership have been reshaping China’s justice and security agendas to strengthen both the authoritarian rule of the Party and the authoritarian rule of law. They advocate what they call ‘rule of law thinking’ 法治思维 to rebuild public trust in the country’s politico-legal institutions, which include courts, procuratorates (the institutions encompassing public investigators and prosecutors), police, national security and para-policing agencies. This is a strategic shift, following a decade of weiwen 维稳, or ‘Stability Maintenance’, a political program closely associated with the Hu Jintao–Wen Jiabao era that covers a range of politico-legal activities aimed at preventing and/or breaking up collective protests and dealing with court cases raised by individual complainants.

At the height of its use in the mid- to late 2000s, and as discussed in previous China Story Yearbooks, the weiwen program gave local courts considerable flexibility in resolving civil and administrative disputes, encouraging judicial mediation over litigation. Mediation arguably favours the interests of local government and local developers more than it does those of the complainants. This trend, often referred to as the ‘localisation of justice’, fostered judicial corruption and errors of justice, further fuelling the very discontent and instability that weiwen was meant to quell (see the China Story Yearbook 2013: Civilising China, Chapter 4 ‘Under Rule of Law’, p.202).

Xi Jinping’s idea of Shared Destiny within China is based on the requirement of ‘unity of thought’ 统一思想, especially in relation to social and political problems that may threaten stability. In promoting the rule of law, he seeks to create a strong underlying judicial and legal framework that will encourage public trust in the legal system and enhance the efficacy of the current political structure. Rebuilding the credibility of politico-legal institutions is a declared objective of reforms across the justice spectrum. The party leadership has demanded that all of China’s courts, prosecution, police, national security and para-policing agencies work together towards this goal, which aims not just to ensure public security (and the security of the Party) but also to create a stable environment in which the Party can carry out its ambitious economic reform agenda.

Party-inspired ‘unity of thought’ is by definition largely intolerant of pluralism and dissent. This can make for a seemingly uneasy relationship with rule of law thinking: at the same time that Chinese leaders are seeking to strengthen judicial institutions to inspire popular trust in the process of law, they are cracking down on public expressions of dissent, including those that some would argue fall within the legal or constitutional rights of Chinese citizens. In late 2013, for example, the government criminalised the online spreading of rumours by including such behaviour within the definition of the crime of defamation. Arresting independently-minded public intellectuals and pro-human rights lawyers such as Pu Zhiqiang 浦志强 in the lead-up to the twenty-fifth anniversary of the 1989 Protest Movement was also, presumably, a pre-emptive strike to discourage disunity in thought and practice over this sensitive period.

The Handle of the Dagger

Xi Jinping requires unity in practice as well as thought within the nation’s justice and security agencies. As noted above, from late 2012, Xi’s leadership has downplayed the ‘Stability Maintenance’ strategy of Hu Jintao. In late 2013 and in 2014, the Party moved to strengthen its central oversight of the administration of law and justice.

The term ‘the handle of the dagger’ became popular after Xi Jinping used it in his keynote address at the 2014 National Conference on Politico-legal Work. The term implies a battle: a fight against corruption, dissent and terrorism

Photo: Weibo/chinadigitaltimes.net

The party leadership was aware that it had to win back the hearts and minds of people whose trust in the law had been seriously eroded by political and judicial corruption, and who had become more inclined to seek justice through collective protests and petitions than through the legal system. ‘Unity of thinking’ on law and justice thus seeks to shift public understanding of the locale of justice from the streets back to officially regulated spaces within the legal system.

In his keynote address at the National Conference on Politico-legal Work on 8 January 2014, Xi Jinping who, as noted earlier, heads the new National Security Commission and Central Leading Group for Internet Security among other posts, declared that China’s politico-legal organs need more than ever before to play a pivotal role in bringing about sustainable economic growth and social stability. Over the coming years, he said, introducing a key new metaphor, politico-legal organs will be required to act as the ‘dagger-handle’ of the Party 党的刀把子. This language implies a battle: a fight against corruption, dissent and terrorism. (For the etymology of the term, see Chapter 4 ‘Destiny’s Mixed Metaphors’, p.146ff.)

While the Party’s leader wields the metaphorical dagger, in the words of China’s anti-corruption chief Wang Qishan, the Discipline and Inspection Commission (the internal party agency that investigates corrupt party members) wields the ‘Sword of Damocles’. Tony Saich, a scholar whose research focuses on Chinese politics and governance, has labelled this ‘the most ambitious anti-corruption campaign since at least Mao’s days’. Some Chinese commentators describe the goal in language reminiscent of the Cultural Revolution: to ‘sweep away all monsters and demons’ 横扫一切牛鬼蛇神.

Wang Qishan serves as Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection and is the public face of Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign

Photo: gbtimes.com

The use of Maoist rhetoric, including terminology such as ‘dagger-handle’, may seem incongruent with rule of law thinking; Mao, after all, referred to the politico-legal system as the ‘tool of the proletarian dictatorship’. The prominent Hangzhou-born commentator Qian Gang , director of the China Media Project at Hong Kong University, was among those analysts taken aback by Xi’s use of Maoist terminology. Qian distinguishes between ‘light red’ discourse such as the ‘China Dream’ and harder core ‘deep red’ Maoist terminology, noting: ‘A dagger-handle is what greets us when we open the door to 2014.’ This ‘deep-red’ metaphor informs Xi’s political approach to reform and indicates his determination to conquer entrenched socio-political problems left over from the time of Hu Jintao, who supported high-speed economic growth at any cost.

The Fourth Plenum’s Rule of Law Ideology

Rule of law is now the Party’s umbrella term that signifies its overall governance intentions for the next eight years. The Xi Jinping leadership seeks to build its legitimacy and to improve its legal system not by distancing the Party from the affairs of the justice system, but the very opposite. This clearly emerges from the resolutions issued after the Third and Fourth Plenums of the Eighteenth Party Congress in, respectively, November 2013 and October 2014. Both documents reiterated Xi Jinping’s focus on the rule of law and the re-invigoration of the authority of the Party in Beijing.

The Party will enhance its oversight of legal and governmental institutions so that they operate within a tight ‘Rule of Law Framework’ 法治的框架内, as Premier Li Keqiang puts it, and implement policy from the top down. The Resolution of the Party’s Fourth Plenum (CCP Central Committee Decision Concerning Some Major Questions on Comprehensively Advancing the Country in Accordance with the Law issued on 28 October 2014), states that the Party’s supremacy and socialist rule of law are compatible 党的领导和社会主义法治是一致的. In fact, the document insists that the Party will now ‘implement its leadership role through the rule of law’ 把党的领导贯彻到以法治国.

Rule of law discourse also has an important ideological role to play. The Party intends it to guide both the thoughts and behaviour of the citizenry and their political masters alike. To this end, the Resolution introduces the idea of integrating two principles of governance: ‘ruling the nation in accord with the law’ 以法治国 and ‘ruling the nation in accord with virtue’ 以德治国. The latter intends to foster a sense of morality in Chinese society and state. At the same time, the Party intends to ‘rule the nation in accord with the law’ by making central, provincial and local party politico-legal committees responsible for unifying thought and action in the realm of law and politics. They are to do this by ‘standardising’ judicial decision-making and improving the transparency and credibility of the judicial process.

The Resolution includes mention of the Constitution because the ideological principles established in the Preamble of the Constitution explicitly give the Party the leading political role in governing China. The Preamble ostensibly places the Party above all laws and other provisions in the Constitution.

Recentralising the Nexus of Law and Politics

Xi’s push for the rule of law had begun to gather pace from mid-2013 onwards, culminating in the Resolution of October 2014. A succession of statements by Xi in 2013, a series of Supreme People’s Court (SPC) and the Party’s Central Politico-Legal Commission (CPLC) reform announcements from July to October 2013, and the Party Congress Third Plenum Resolution of November 2013 revealed plans to ‘de-localise’ justice agendas and to ‘re-centralise’ party, SPC and politico-legal power. Key phrases coming out of the Third and the Fourth Plenums included: ‘transparency’, ‘supervision’, ‘institutionalisation, standardisation and proceduralisation’, ‘judicial openness’, ‘judicial independence’, ‘judicial fairness and credibility’, ‘standardising judicial decision-making’ and ‘preventing miscarriages of justice’.

The overall focus is on promoting stronger oversight of political and judicial authorities at the local level. In July 2013, the Party’s main law-and-order body, the CPLC, issued a strongly-worded directive, titled Provisions on Preventing Miscarriages of Justice 防止冤假错案, aimed at thwarting abuses of power and miscarriages of justice in local courts. The Chinese law expert Jerome Cohen describes the directive as ‘stunning’ in scope, and largely empty of ideological clichés. The Provisions ‘go beyond the [usual] recitation of relevant norms’, Cohen says, to specify how the Party expects prosecutors to supervise the work of police and judges; how judges must withstand pressure from local interests (whose main concern is likely to be maintaining social stability) during the adjudication process; and how party politico-legal committees, which will still coordinate the work of the courts, police and prosecutors, must refrain from interfering in judicial decision-making.

Jerome A Cohen is an expert on Chinese law and an advocate of human rights in China

Photo: its.law.nyu.edu

The Provisions and other reform documents published in 2013 and 2014, including the new SPC five-year plan for court reform issued on 9 July 2014, indicate that the SPC has made a priority of reconfiguring central-local judicial decision-making so the centre can exercise greater control over local courts. They list important justice reforms such as shifting responsibility for resourcing courts from the local to the provincial level. This move makes it much harder for local political authorities to threaten local judges and courts with withdrawing revenue in order to obtain favourable outcomes in administrative and civil disputes with local residents. The SPC intends to limit judicial discretion and inconsistency — especially in administrative or civil disputes that touch on social stability concerns — while enhancing transparency, including by posting judgments on court websites.

Reform documents strongly encourage courts to ‘unify’ 统一 their decision-making. To this end, the SPC has stepped up its case guidance system, promoting a number of model cases that illustrate best practice. These models enable local courts to ‘standardise’ 规范化 disparate and uneven decision-making to achieve greater consistency in adjudicating and sentencing. This will make it possible to declare with confidence that ‘similar judgments are made in similar cases’ 同案同判 across the nation: unity of thinking and action within the justice system.

Enhancing Judicial Accountability

The SPC employs a number of high-profile reformist judges, including its President, Zhou Qiang 周强, and Deputy President, Shen Deyong 沈德咏, who are both keen to abandon the Stability Maintenance practices (including the ‘aggressive mediation’ detailed above) that have sullied the reputation of courts in recent years. To this end, Xi Jinping has ordered politico-legal officials to ‘carry the sword of justice and the scales of equality’. The courts must safeguard social justice and equality, while protecting people’s interests.

Three important SPC opinions promulgated in late 2013 bring into sharp relief the reforms that the SPC and the Party intend to pursue in the coming years:

- Opinion on Improving Judicial Credibility (28 October 2013)

- Opinion on Improving Judicial Transparency (21 November 2013)

- Opinion on Preventing Miscarriages of Justice (21 November 2013)

While these Opinions do not carry the same weight as law, they are nevertheless important indicators of a change in the general direction of legal development in China. The Opinion on Improving Judicial Credibility unveils the broad agendas for judicial reform. It appeals to judges to focus on ‘justice for the people’ and practical changes in the work style of the courts, as stated above: limiting judicial discretion and standardising and ‘unifying’ judicial decision-making in order to discourage venal practices that have led to the favouring of the interests of local developers and government over those of local citizens.

Among the model cases posted by the SPC in early 2014 are seven new cases relating to the ‘livelihood of the masses’. In one, the litigant sought compensation for the forced demolition of a property; another dealt with a copyright infringement case. There is also a judicial review case involving a farmer’s complaint about water pollution and another involving two men pursuing compensation for wrongful incarceration.

The execution of street vendor Xia Junfeng for killing two chengguan, urban law enforcement officers, sparked an outcry on Chinese social media sites

Photo: Xinhuanet.com

The Opinion on Improving Judicial Transparency announced ‘three platforms of openness’: judicial transparency in regard to trials in process; the disclosure of case results; and the disclosure of information regarding the enforcing of court verdicts. It involves providing general information on court websites about provisions and procedures relating to litigation processes, documents, fees, risks and alternative dispute resolution mechanisms such as mediation.

The Opinion on Preventing Miscarriages of Justice, meanwhile, confirms provisions made in the revised 2012 Criminal Procedure Law on excluding evidence obtained through torture and other illegal means. It requires judges to follow strictly legal procedures and reminds courts of appeal that they are responsible for counterchecking judgments in cases where the evidence was sketchy or the facts unclear. It also provides for senior judges to adjudicate in cases involving capital punishment. (The number of executions carried out each year remains a state secret.) The Opinion also attempts to put a halt to the trend over the last decade of courts and judges sometimes acquiescing to populist demands — especially when state officials are perceived to have provoked suspects or defendants to violent acts of revenge. The Opinion on Preventing Miscarriages of Justice declares that: ‘people’s courts … should not make any judgments that contravene the law under the pressure of public opinion or of involved parties’ appeals, or in the name of “maintaining social stability” ’.

An example is the case of Xia Junfeng 夏俊峰, an unlicensed street vendor arrested in 2009 for the murder of two chengguan 城管 (urban law enforcement officers). Xia alleged that the chengguan had beaten him and that he acted in self-defence (see Forum ‘The Execution of Street Vendor Xia Junfeng’, p.300). The SPC came under considerable popular pressure not to approve Xia’s execution but it refused to bow to public sentiment.

On the other hand, following continued public outcry over scandals involving the treatment of petitioners in ‘reprimand centres’ and ‘black jails’, in February 2014 the Party’s Central Committee and the State Council introduced new guidelines for reforming and regularising the way that politico-legal institutions deal with petitioners voicing grievances against officials and calling for redress. The document stresses the importance of the rule of law in handling petition cases and expands the public channels by which petitioners may appeal to officials, including the establishment of a website that encourages virtual petitioning rather than requiring that petitioners visit government buildings in person.

Abolishing Re-education Through Labour

Tang Hui 唐慧, from Yong-zhou, Hunan province, was sentenced to one and a half years of labour re-education for demanding tougher punishment for those who allegedly raped and forced her daughter into prostitution. She was released eight days later following a huge public outcry

Photo: backchina.com

The international media have highlighted the decision announced by the Third Plenum to abolish the system of Re-education Through Labour (RTL劳动教养), the use of administrative detention that has been employed for decades to allow police and other authorities to incarcerate people for up to four years for minor crimes without the inconvenience of going through a trial. Such crimes included petty theft, prostitution and the trafficking of illegal drugs, but also religious or political dissent: for example, attending the prayer meetings of a proscribed church group or speaking out on a subject the authorities deemed unacceptable.

According to the Resolution of the Plenum, an enhanced system of ‘community corrections’ would replace RTL. During the last ten years, the authorities in some jurisdictions have experimented with a system of ‘community corrections’ 社区矫正 whereby offenders spend their sentence in community service. To date, it is still unclear how this mechanism will be used and what the procedural requirements for its application will be. The Ministry of Justice is now working toward a final draft of a new Community Corrections Law to solve these uncertainties, standardise diverse practices of ‘community correction’ around the country and to regulate this expanded institution.

The reform of RTL has also generated debate about the legality of other forms of detention, including those replacing RTL. These include the ‘custody and rehabilitation’ 收容教养 of juveniles, prostitutes and those who procure their services; ‘black jails’ 黑监狱 for petitioners who have not been charged with a crime but whom the authorities deem inconvenient or offensive; ‘criminal detention’ 拘留 for pre-trial criminal suspects and ‘residential surveillance’ 监视居住. The last was originally an alternative to pre-trial detention but is now used as a form of extra-legal house arrest for activists, their close relatives (such as the imprisoned Nobel Peace Laureate Liu Xiaobo’s 刘晓波 wife, Liu Xia 刘霞) and individuals accused of undermining stability.

On 21 March 2014, a group of human rights lawyers were arrested in Jiansanjiang, Heilongjiang province, after they visited a black jail. On 25 March, six lawyers began a hunger strike outside the Qixing Detention Centre when their request to meet with the detained lawyers was refused

Photo: voanews.cn

Authoritarian Rule of Law in Practice

In 2014 (as in previous years), the government showed the authoritarian nature of Beijing-style rule of law when it detained or arrested a number of lawyers who have been arguing for citizens to enjoy the rights prescribed in Chinese law and the constitution as well as anti-corruption campaigners and advocates of greater political and fiscal transparency.

22 January 2014: Well-known human rights lawyer Xu Zhiyong was sentenced to four years in prison for breaching the 1997 Criminal Law by ‘gathering a crowd to disrupt order in a public place’

Photo: 37dts.com

During the first half of the year, in the lead-up to the sensitive twenty-fifth anniversary of the 1989 Protest Movement and its violent suppression, the authorities imposed charges of ‘disrupting public order’ on individuals and groups to silence its critics, some pre-emptively. Among them was the lawyer Xu Zhiyong 许志永, a founder of the New Citizens’ Movement 新公民运动 (see Forum ‘Xu Zhiyong and the New Citizens’ Movement’, p.292) and one of the most high-profile human rights lawyers and activists of the last decade.

On January 2014, the Beijing Number One Intermediate People’s Court sentenced Xu to four years in prison for ‘gathering a crowd to disrupt order in a public place’ 聚众扰乱公共场所秩序 according to Article 291 of the 1997 Criminal Law. The charge referred to his role in organising and calling on people to unfurl banners, distribute leaflets, attract onlookers, make a racket and obstruct police officers from enforcing the law during a series of protests in 2012 and 2013. Three months later, the Beijing Higher People’s Court upheld Xu’s guilty verdict on appeal, sparking outrage among human rights advocates both inside and outside China.

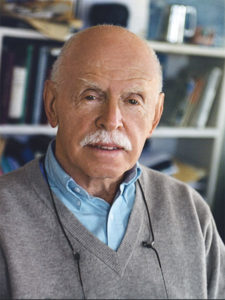

On 4 June 2014, tens of thousands of people gathered in Hong Kong’s Victoria Park to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Beijing massacre. In mainland China, commemoration of the anniversary is strictly forbidden

Cartoon: Baiducao, TAM

Repression in the name of public order became more common in the months leading up to the twenty-fifth anniversary of the 1989 Protest Movement. Emblematic of Beijing’s attitude towards ‘disunity of thinking’ was the case of lawyer Pu Zhiqiang, detained on 5 May on suspicion of ‘picking quarrels and provoking troubles’ 寻衅滋事 (Article 293 of the Criminal Law) — in this case, he was guilty of attending a small, private commemoration of the 1989 student protest. A Global Times commentary published on 8 May on Pu’s detention claimed that by meeting to commemorate the Tiananmen events, the human rights lawyer had ‘clearly crossed the red line of law’.

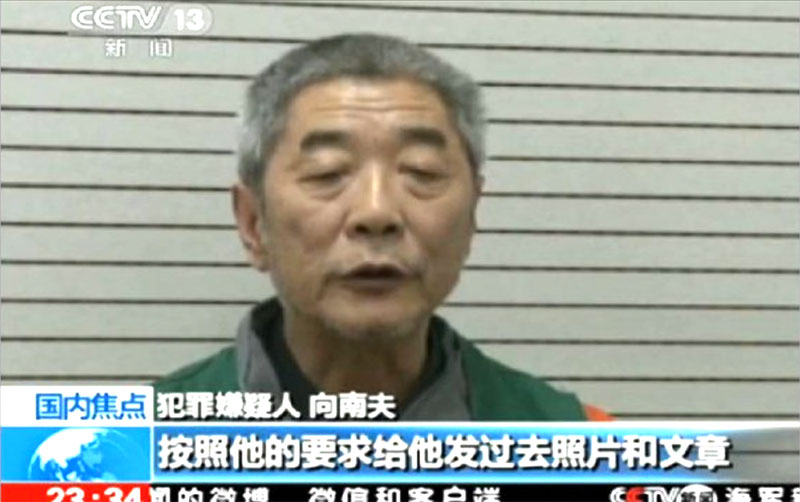

These developments in early 2014 revealed the party-state’s new approach to quelling dissenting voices. Rather than pursue outspoken critics on charges of subverting state security, they charge them with common public order offences. The Dui Hua Foundation research group claims that the number of people charged with subversion, separatism and incitement to subvert state power decreased by twenty-one percent in 2013 to 880 individuals, while the number of those charged with disrupting public order has increased dramatically — from around 160,000 in 2005 to more than 355,000 in 2013. Other dissenters besides Pu Zhiqiang who have been charged with the seemingly innocuous offence of ‘picking quarrels and provoking troubles’ include the labour activist Lin Dong 林东 and the Boxun 博讯 journalist Xiang Nanfu 湘南富, among others.

This strategy is reminiscent of the way in which the dissident artist Ai Weiwei was dealt with in 2011: the authorities charged the outspoken critic of the Party with tax evasion. Similarly, in June 2014, they charged the Australian-Chinese artist Guo Jian with ‘visa fraud’ before deporting him to Australia. Both instances are examples of the way the party-state cynically attempts to deflect criticisms of human rights abuses by smearing the character of dissidents, implying that they were fraudsters or common criminals.

3 May 2014: A citizen journalist for the US-based website Boxun, Xiang Nanfu, is arrested and paraded on state television

Photo: CCTV

27–30 April 2014: Xi Jinping visits the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region where he vows to ‘strike first’ against terrorism

Photo: Xinhua

On 27 May 2014, fifty-five people were sentenced at a mass trial in Yili, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. At least three people were sentenced to death. Others were jailed for murder, separatism and organising or participating in terror groups. Xinhua claimed that around 7,000 locals and officials withnessed the mass sentencing

Photo: voanews.com

The authorities are more comfortable with pinning charges of subversion and separatism on those in the restive north-western ethnic region of Xinjiang who do not share Xi Jinping’s vision of their place in China’s Community of Shared Destiny. The robust ‘unity of thinking’ underlying Xi Jinping’s approach operates in this case, however, as a double-edged sword. As the journalist Chris Buckley noted in The New York Times, Xi has ‘cast himself as a paternal leader devoted to improving the lives of ordinary people’ and sees the assimilation policies towards the Uyghurs not as the source of discontent but as the means to its resolution.

In October 2014, fifteen suspects were driven through the streets of Yueyang, Hunan province, on the back of a truck labelled the ‘Prisoner Van’, before being taken to a public trial that was watched by thousands

Photo: Weibo

In May, the central authorities called on the three arms of state justice — the police, the procuratorate and the courts — to coordinate their work against terrorism 暴恐主义, declaring a year-long ‘People’s War on Terror’ (see Forum ‘Terrorism and Violence in and from Xinjiang’, p.308) primarily aimed at Xinjiang separatists. Within one week of this declaration of war, on 27 May, police, prosecution and judicial forces rounded up both suspects and convicted criminals and put them on display at a major public shaming rally in the city of Yili. They paraded these criminal and terrorist suspects and convicted offenders at a large public arena in the style of the Strike Hard 严打 anti-crime campaigns of the 1980s and 1990s. The suspects received their sentences in front of over 7,000 people, including schoolchildren.

Although in the 1980s the Supreme People’s Court outlawed the public parading and humiliating of convicted criminals and suspects, including by driving them through the street in trucks, an exception was apparently made for this opening salvo of the ‘People’s War on Terror’. The following day, the Legal Daily 法制报 applauded the public ritual: ‘These kinds of rallies are an important way for the people to see for themselves the outcomes of our efforts. They will improve the resolve of criminal justice organs (to fight the war) and will console the victims of terrorism.’

Contesting the Rule of Law

Muslim separatists and human rights advocates alike reject the idea of a Party-led rule of law. It is also clear that some in the party hierarchy, including its leftist wing, are not comfortable with the new rule of law thinking. A week before the Fourth Plenum Communiqué was announced, an article on law and politics in the Central Party School mouthpiece Red Flag 红旗 declared that it is not rule of law but ‘the people’s democratic dictatorship’ that must be urgently realised across the nation. ‘The Party must guarantee the fundamental interests of the labourers and masses and not substitute these interests for those who will benefit from the rule of law.’

Others have chosen more practical means of contesting Xi’s rule of law ideology. On the very day that the Fourth Plenum Communiqué was announced, another old-fashioned Maoist public sentencing rally hit the news headlines in Mao’s home province of Hunan. Authorities in Huarong county convened a joint ‘public arrest and public sentencing rally’ to put on public display sixteen suspects and eight convicted criminals, who were then placed in trucks and paraded on the streets following the outlawed practice. ‘The three heads’ (of the local police, prosecution and court) jointly organised the event to mark their local ‘strike hard’ campaign against robbery. While the event itself occurred three days before the Plenum, Hunan authorities waited until the day the Fourth Plenum Communiqué was released to broadcast the vision of the parading trucks on the television news. While social commentators and bloggers noted this ‘coincidence’, Beijing was initially silent. Three days later, Xinhua issued an editorial in the Beijing News 新京报, declaring in high dudgeon tones that the event ‘proved that ruling the people is easy while ruling (local) officials is the difficult part’.

Conclusion

One constant that has been on display in the justice arena in China over the last three decades is the idea that broad national political discourses — Harmonious Society, Stability Maintenance and so on — set the context for how justice is dispensed. These political watchwords shape the way in which justice is conceptualised and practised. To this list, we can now add ‘comprehensively advancing the rule of law’, a recycled catchphrase from the Deng Xiaoping era but now with some additional ‘Xi Jinping characteristics’.

Xi Jinping’s interpretation of the rule of law includes his ability, as the head of the new National Security Commission and the Central Leading Group for Internet Security, to wield the dagger against terrorists while the Discipline and Inspection Commission under Wang Qishan wields the sword against corrupt officials.

Xi Jinping’s commitment to ‘recentralising’ justice is not some kind of ideological battle for judicial independence, nor an effort to wrest ‘law’ from the clutches of ‘politics’. His purpose is to decouple law from the dirty politics of local corruption and protectionism, and to meld it with the supposed ‘clean’ politics of central party oversight; this is what he means by governing ‘in accordance with the law’. Standardising and unifying judicial and policing practices across the legal system will indeed help improve judicial fairness and efficiency. It will also help to legitimise Xi’s administration and policies.

Yet Xi’s insistence on doing this ‘the party way’ places potentially irreconcilable, contradictory demands on the courts and other agents of justice. It will be difficult for them to deliver ‘justice for the people’ while ‘unifying’ with the centre. Indeed, the government’s requirement that the judicial organs join the battle to ‘unify thinking’ places the credibility of the justice system in question even as it is ridding itself of some of its most questionable historic practices.

Notes

Elizabeth LaForgia, ‘China detains rights lawyer ahead of Tiananmen Square anniversary’, Jurist, 7 May 2014, online at: http://jurist.org/paperchase/2014/05/china-detains-rights-lawyer-ahead-of-tiananmen-square-anniversary.php

‘统一思想 开启政法工作新航程’, Xinhua, 1 October 2014, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/legal/2014-01/10/c_125983523.htm

‘Make discipline inspection “Sword of Damocles”: anti-corruption chief’, Xinhua, 15 March 2015, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2014-03/15/c_133188981.htm

Shai Oster, ‘President Xi’s Anti-Corruption Campaign Biggest Since Mao’, Bloomberg, 4 March 2014, online at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-03-03/china-s-xi-broadens-graft-crackdown-to-boost-influence.html

钱钢, ‘观点:2014,开门就见“刀把子”’, BBC Chinese News, 11 January 2014, online at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/zhongwen/simp/china/2014/01/140111_comment_shank_progapanda_law.shtml

‘李克强强调:打造奋发有为守法清廉的机关党员队伍’, The People’s Daily, 1 April 2014, online at: http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2014/0401/c1024-24797428.html

Jerome A. Cohen, ‘Struggling for Justice: China’s Courts and the Challenge of Reform’, World Politics Review, 14 January 2014, online at: http://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/13495/struggling-for-justice-chinas-courts-and-the-challenge-of-reform

‘案例指导制度与同案同判’, The People’s Daily, 29 January 2014, online at: http://theory.people.com.cn/n/2014/0129/c107503-24256966.html

Xinhua, ‘President Xi stresses vitality and order in rule of law’, The People’s Daily, 9 January 2014, online at: http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90785/8507456.html

Susan Finder, ‘The Supreme People’s Court 2013 Judicial Reform Opinion: A Flash Analysis (Part 1)’, Supreme People’s Court Monitor, 30 October 2013, online at: http://supremepeoplescourtmonitor.com/2013/10/30/the-supreme-peoples-court-2013-judicial-reform-opinion-a-flash-analysis-part-1/

‘最高人民法院发布人民法院保障民生典型案例’, China Court Internet, 17 February 2014, online at: http://www.chinacourt.org/article/detail/2014/02/id/1214868.shtml; Also see Susan Finder, ‘The Supreme People’s Court New Petitioning Measures’, Supreme People’s Court Monitor, 2 March 2014, online at: http://supremepeoplescourtmonitor.com/2014/03/02/supreme-peoples-courts-new-measures-to-resolve-the-petitioning-problem/

Cao Yin, ‘Courts ordered to make trials more transparent’, China Daily, 28 November 2013, online at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2013-11/28/content_17136369.htm. See also China Law Translate, ‘SPC Opinion On 3 Platforms For Judicial Transparency’, China Law Translate, 29 November 2013, online at: http://chinalawtranslate.com/en/spc-opinion-3-platforms-for-judicial-transparency/

Xinhua, ‘China petition reform vows rule of law’, Xinhua, 25 February 2014, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2014-02/25/c_126190243.htm

Jeremy Daum, ‘Updated: Quick Note on Picking Quarrels’, China Law Translate, 6 May 2014, online at: http://chinalawtranslate.com/en/quick-note-on-picking-quarrels/

Didi Tang, ‘China hits activists with common-crime charges’, AP News, 27 May 2014, online at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/china-hits-activists-common-crime-charges

‘A Safer, More Harmonious China?’, Dui Hua, 11 March 2014, online at: http://duihua.org/wp/?page_id=8836

Chris Buckley, ‘In Xinjiang, Xi Pushes Vision of Uighur Integration’, The New York Times, 29 April 2014, online at: http://sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/04/29/in-xinjiang-xi-pushes-vision-of-uighur-integration/

李新安, ‘新疆伊犁州举行公判、公捕、公拘大会 对55名被告人公开宣判’, The People’s Daily, 27 May 2014, online at: http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2014/0527/c1001-25072595.html

‘为公判公捕叫好’, Legal Daily, 28 May 2014, online at: http://www.legaldaily.com.cn/locality/content/2014-05/28/content_5556209.htm

‘红旗文稿连续两期刊发论人民民主专政文章,法治不能代替专政’, The Paper, 12 October 2014, online at: http://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1270719

Zhou Dongxu, ‘Despite Ban, County Holds Convict Parade Days before Rule of Law Plenum’, Caixin, 24 October 2014, online at: http://english.caixin.com/2014-10-24/100743021.html

‘[媒目]公捕公判:早该停止的强权游戏’, The Beijing News, 23 October 2014, online at: http://www.bjnews.com.cn/focus/2014/10/23/338499.html