In the 2012 Corruption Perceptions Index report by Transparency International, China ranked eightieth out of the 176 countries surveyed, with a score of thirty-nine from a possible one hundred. By contrast, Singapore is ranked fifth with a score of eighty-seven, Hong Kong fourteenth with a score of seventy-seven and Taiwan is in thirty-seventh place with a score of sixty-one. These comparisons show that China’s corruption cannot be due to some specific way people of a Chinese cultural background conduct business or public administration. Since he assumed the presidency, Xi Jinping has refocused the attention of government on the eradication of corruption, using not only the instruments of state power to arrest and detain offenders but also traditional methods of persuasion to encourage civilised behaviour in the community as a whole. Whether such methods, pioneered in the early years of the People’s Republic, and in fact even earlier, are still effective remains an open question.

Fighting Tigers and Flies

In the first public speech Xi Jinping made after becoming General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party on 15 November 2012, he nominated graft and corruption as the most important problems facing the Party. On 19 November, he expanded on these remarks to the new Politburo, declaring that ‘corruption could kill the Party and ruin the country if it were to increase in severity and [so] we must be vigilant’. Speaking too of ‘the overthrow of governments’, he seemed to be making an oblique reference to the Arab Spring, blaming endemic corruption in those countries for popular discontent and social unrest. Xi’s comments might be dismissed as merely the ritualistic denunciation of corruption, as his two predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao both made similar remarks: Jiang in 2000, and Hu on two occasions — in 2007 and in his opening address to the Eighteenth Party Congress in 2012. However, the appointment in 2012 of Vice-Premier Wang Qishan, the Party’s chief troubleshooter, to head up the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection of the Communist Party was an indication of Xi’s seriousness in this arena.

On 22 January 2013, Xi followed up on his November pronouncements with a more pointed declaration of intent. The Party would not just stamp out transgressions among the leadership of the country but it would address infractions of discipline by local officials as well. In what may become one of Xi’s best-known slogans, he asserted that ‘we must fight tigers and flies at the same time’ (yao jianchi ‘laohu’, ‘cang-ying’ yiqi da 要坚持‘老虎’、‘苍蝇’一起打). Xi’s targets included the extravagant banquets and other luxury perks that officials have long enjoyed, as well as the kind of petty bureaucratic formalism that includes endless speechifying and elaborate, expensive and self-aggrandising ceremonial events. If the Party failed to address this culture of corruption, he warned, then ‘it will be like putting up a wall between our Party and the people, and we will lose our roots, our lifeblood and our strength’. To prevent corruption occurring in the first place, power should be exercised within what he called ‘a cage of regulations’.

Corruption is undeniably one of China’s most pernicious problems. In October 2012, He Guoqiang, Wang Qishan’s predecessor at the Discipline Commission, reported that between 2007 and 2012, the commission found more than 660,000 officials guilty of ‘disciplinary violations’. It handed 24,000 officials suspected of committing crimes over to the judicial authorities. In the first half of 2012 alone, it had punished 377 officials from ‘major state-owned enterprises’ and found that 1,405 officials in law enforcement agencies had abused their power and aided criminal organisations. In September 2012, subsequent to the local elections held that April in Zhejiang province, it cancelled the nomination of forty-four cadres because they failed in the morals examination, while seventy-nine others ‘were warned, transferred from their original posts and removed because of their poor marks’. In January 2013, Xinhua reported that 7.83 billion yuan had been recovered the previous year through investigations of corrupt officials. Central Chinese Television characterised the 2012 campaign as ‘an anti-corruption storm’ sweeping across the country.

Over the last few years, Chinese news services have regularly featured the falls from grace, arrests and convictions of former leading officials. Popular outrage over six babies dying and another estimated 54,000 admitted to hospital after infant formula had been found to be tainted with melamine (a scandal allegedly hushed up before the 2008 Beijing Olympics) led to the execution of two officials in 2009 and the jailing of nineteen more for long sentences. Since then, food contamination cases have regularly occurred across the country: in 2010, investigators discovered green beans had been contaminated by illegal pesticides in Wuhan and, in April of the same year, they confiscated seven million takeaway food containers in Jiangxi province found to be poisonous. Inspectors found the steroid clenbuterol in pork as recently as 2011; the contamination was feared to be so common that China banned its athletes competing at the 2012 London Olympics from eating Chinese-produced products for fear of breaching drug testing guidelines. The use of cooking oil recycled from restaurant drains and sometimes combined with even more dangerous non-food oils, a product known colloquially as ‘gutter oil’ (digouyou 地沟油), is also alleged to be widespread. In 2011, tests discovered that twenty-eight percent of samples of food made from flour in Shenzhen had aluminium levels well above national limits, and studies continue to identify extensive cadmium contamination in rice grown across the country. Most recently, in May 2013, the Ministry of Public Security arrested sixty-three people in Shanghai and Wuxi for selling gelatin-treated rat, mink and fox meat as lamb.

In the famously corrupt world of Chinese football, two former heads of the national association, four members of the national team and China’s best-known referee were all jailed in June 2012 for between five-and-a-half and ten-and-a-half years for taking bribes. Recently, in May 2013, no fewer than twenty-one officials from Chongqing were disciplined for corruption, three of whom face criminal charges following the leaking of a sex video featuring Lei Zhengfu, the party head of Beibei district in Chongqing municipality, onto the Internet. This case is but one of many where the dalliances of officials, whose mistresses have often also been implicated in corruption, have been exposed. In April 2013, Liu Zhijun, the former Railways Minister who presided over the vast growth in China’s high-speed rail system, was charged with corruption — in 2011, Liu had been dismissed from his post and last year was expelled from the Party. Apart from the furore over the Wenzhou train crash itself, an investigation by the National Audit Office found that during his tenure, 187 million yuan had been embezzled during the building of the new Beijing–Shanghai line and another 491 million yuan had gone missing in associated land transactions. In July 2013, Liu was given a suspended death penalty.

The Lei Zhengfu sex video case made Beijing blogger, and former journalist with the Procutorial Daily (Jiancha ribao 检察日报), Zhu Ruifeng famous among China’s online community as it was his Hong Kong-based website People’s Supervision Network that published the video. After he uploaded the video, a former journalist on the Southern Capital Daily, Ji Xuguang posted stills from it on his Weibo account, allowing it to spread across the Chinese Internet. The case was remarkable not only for its squalor but also for the unusually speedy official response: only sixty-three hours had lapsed between the uploading of stills onto Weibo and the Chongqing government announcement that they were removing Lei from his post.

In December 2012, Zhou Lubao — whom the China Daily referred to as a ‘muckraking netizen’ — noticed that the mayor of Lanzhou (the capital of Gansu province), Yuan Zhanting, had worn five different expensive watches in publicity photos. One of the watches was revealed to be a Vacherin Constantin that retails for more than 200,000 yuan, one was a gold Rolex and another a 150,000-yuan Omega.

The clampdown on corruption has already affected luxury consumer items commonly used for bribes, tax evasion or simply ostentatious consumption. The first quarter of 2013, for example, saw imports of Swiss watches drop twenty-four percent and those of expensive French wine plummet. Sales of shark fins for soup have fallen an extraordinary seventy percent — a result to please environmentalists. Pernod Ricard, owner of Ballantines and Chivas Regal, reported their first annual fall in whisky sales in China in March 2013; their first foray into the China drinks market was in 1987. The decline in luxury alcohol sales has not just hit foreign brands. Moutai, the premium Chinese baijiu or clear liquor, saw its profit growth halved in the first quarter, and sales of Shuijingfang — the first baijiu company bought by overseas interests, in this case the British drinks conglomerate Diageo — fell by forty percent in the same period. Another area of consumption that has seen a steep decline has been in the purchase of gift cards. In 2011, some 600 billion yuan of cards were sold and the market was growing at between fifteen to eighteen percent annually. New regulations were enacted in May 2011 to prevent, in the words of the State Council, ‘money laundering, illegal cash withdrawal, tax evasion and bribery’. Subsequently, for transactions exceeding 10,000 yuan, the gift card issuer had to register the purchaser’s name and the names of the people who would redeem them. Furthermore, no card could be issued with a value of more than 5,000 yuan and officials were banned from receiving them in the course of their duties.

China’s Next Top Models

Within the government, the officials who work to stamp out corruption are employed in what is called the ‘disciplinary inspection and supervision system’. Following a pattern established in the early years of the People’s Republic, when the authorities want to stress the importance of certain areas of work, or particular casts of mind, they nominate people deemed especially meritorious as ‘model workers’. Thus, in this field, some individuals have won the title ‘All China Disciplinary and Supervision System Advanced Model Worker’. Like other model workers since the 1950s, they are lauded as selfless, devoted to the Party and their duties and incorruptible; they may even sometimes martyr themselves through enthusiasm for the task or neglect of their own health. Unlike the model workers of high Maoism, shown mindlessly acquiescing to ideological demands in denial of their own individuality, these figures display personal initiative and do not accept the moral rectitude of party officials as a given. Yet at least one anti-corruption model, Shen Changrui, from Changping county district near Beijing, finds his predecessors inspirational: Shen claims to have seen the 1990 movie about the ‘good student of Chairman Mao Zedong’ Jiao Yulu (1922–1964) many times:

Scenes from the film constantly appear in my mind. If you want your office to deal with a petition well, then you have to treat the people with kindness. Think about it: it’s always the common people who are wronged. It’s only when they encounter some thorny issue that the old folk come running out of the mountains to find us. Could that be easy? If you just give them a blank ‘don’t-bother-me’ look, then how are they expected to survive!

Another is Li Xing’ai from Longchang county in Sichuan province. An article published in August 2012 in the Sichuan News Service narrated Li’s anti-corruption exploits. The tone of the introduction gives a flavour of the whole:

For a full twenty-three springs and autumns he has worked like a tireless ox for the people, bowing his head before the plough without resentment and without regret, resolute in the frontline battle of investigations in disciplinary inspection and supervision. He is also like a steadfast woodpecker, looking in all directions with piercing eyes and never failing in his task, determinedly extracting swarming putrid termites from dark crevices to eat. To the present he has personally investigated more than 400 cases that have led to the punishment of 477 personnel for disciplinary violations, and has retrieved more than twenty million yuan of direct economic losses to the country. What’s more, he is like a loving yet awe-inspiring guardian angel, treating cadres and the masses with overflowing tenderness when implementing disciplinary regulations for the people; he is upright and incorruptible, with majestic righteousness. Time and time again, he has received all manner of commendations from county, city and province … . His deeds show the feelings of a grassroots disciplinary inspection and supervision cadre, a public servant selfless and fearless in carrying out his responsibilities. And they provide an example of a contemporary Communist Party member’s lofty pursuit of his ideals and his passionate loyalty.

Official anti-corruption fighters are mostly the ones who receive this kind of praise. Human Rights Watch reported the detention on 31 March 2013 of four people who staged a demonstration in the Xidan Cultural Plaza in Beijing demanding that officials publicly declare their private financial interests. They reportedly raised large banners with this demand and stated that ‘unless we put an end to corrupt officials, the China Dream can only be a daydream’. Following this demonstration, part of an ongoing campaign that included petitions and open letters, police arrested several other activists on charges ranging from illegal assembly and extortion to ‘inciting subversion of state power’ either for allegedly helping to plan the protest or for demonstrating in support — despite the fact that their demands chime with party policy. All but one of those detained remain in jail. The charge of ‘inciting subversion of state power’ is extremely serious: it is the ‘crime’ for which Nobel Peace Laureate Liu Xiaobo is serving an eleven-year sentence.

The month following the ill-fated demonstration, President Xi addressed the Politburo again on the topic of corruption, this time urging his colleagues to learn from China’s ‘ancient anti-corruption culture’ and to apply ‘historical wisdom’ to the problem. Two stories of officials involved in anti-corruption activities from ‘ancient China’ featured in the Procutorial Daily. One concerned a short text from the Classic of History entitled the ‘Song of the Five Sons’ and the other ‘the first anti-corruption textbook in Chinese history’: the Book of Wakening Corrupt Officials, attributed to Zhu Yuanzhang, the fourteenth-century founding emperor of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

The ‘Song of the Five Sons’ probably dates from the third or fourth century BCE but tells of events that occurred about one and a half millennia earlier. The protagonist is Taikang, the third emperor of the possibly legendary Xia 夏 dynasty who, through neglect of his duties and lack of devotion to the people, lets his state descend into turmoil. James Legge renders the Chinese evocatively: Taikang ‘occupied the throne like a personator of the dead’. Taikang’s five brothers (the sons of the title) relate and decry his behaviour and its consequences in their songs.

When Zhu Yuanzhang ascended the throne, he faced enormous problems of official embezzlement, bribery and corruption. He personally oversaw the investigations and often dictated brutal terms of punishment for transgressors in the bureaucracy, even writing the record of events himself. Mao Zedong deeply admired the way Zhu set about cleansing his administration and the ‘demonic cruelty’ with which he had transgressors punished or executed, as Ming historian Edward L. Farmer characterises his legislative zeal.

The Chinese media have also recently started to retell other anecdotes about incorruptible officials from pre-modern China. These include that of the sixteenth-century mandarin Hai Rui. His story became famous in the 1960s when the Ming historian Wu Han’s play Hai Rui Dismissed from Office (Hai Rui ba guan 海瑞罢官), which implied that Chairman Mao was in fact not listening to upright officials speaking the truth around him, became an early, major target of the Cultural Revolution.

The People’s Daily has even published a guide to ‘The Top Ten Corrupt Officials in Ancient China’. Whether these stories about the battles of the righteous against the corrupt are seriously influencing the behaviour of China’s bureaucrats today, or if this is simply the busy-work of cynical journalists and historians playing their role in a national campaign is hard to say, but the authorities’ faith in providing positive exemplars does not seem to have waned.

The sociologist Børge Bakken has helpfully characterised con-temporary China as ‘an exemplary society’. As he puts it:

The exemplary society … can be described as a society where ‘human quality’ based on the exemplary norm and its exemplary behavior is regarded as a force for realising a modern society of perfect order. It is a society with roots and memories to the past, as well as one created in the present to realise a future utopia of harmonious modernity.

Derrick Rose basketball shoes inspired by Lei Feng. Design features ‘revolutionary screws that never rust’.

Photo: Markuz Wernli

As the title of the People’s Daily guide suggests, exemplars can be both positive and negative. Official historians in imperial times were obliged to designate a biographical subject as worthy of praise or blame. In today’s China, this is no less true, even if, as in ancient times, nuanced judgements of a person’s actions rarely fit such a powerfully binary template. Thus, officially produced books, films, comics and histories feature clear-cut heroes and villains — the better to illustrate what is correct, righteous behaviour on the one hand and what is behaviour that is disloyal, counter-revolutionary, or corrosive of society on the other.

Officially designated model workers or model soldiers offer guidance to the rest of society as to how to work and live. However, because they are by definition so pure, so selfless, so unthinkingly loyal, they become transformed into caricatures of real people, cartoons of goodness. This leaves them wide open to suspicion and makes them the subject of snide asides and satire. A perfect example of this phenomenon can be seen with China’s best-known model citizen, People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldier, Lei Feng.

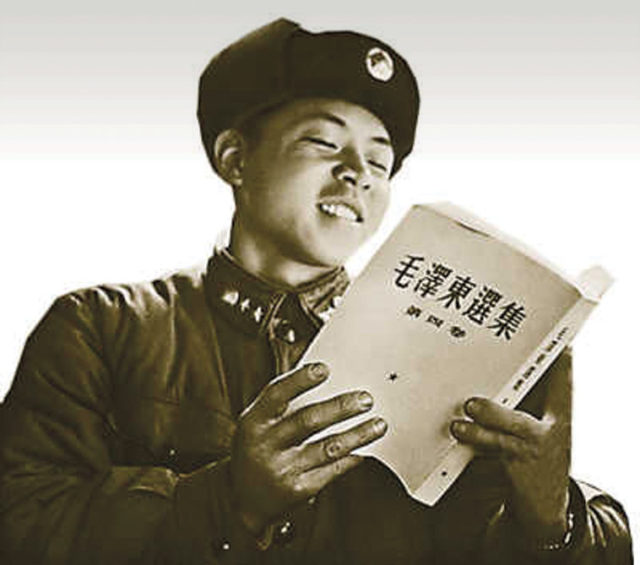

Lei’s official biography relates that he was born in 1940 in Hunan province to a rural family and orphaned at seven. His father had been killed by the Japanese and his mother committed suicide after being raped by the son of a powerful landowner. ‘Adopted by the Party’, as the hagiography puts it, Lei Feng joined the PLA when he was twenty and was transferred to Liaoning province in the northeast. He died in 1962 when he was hit by a telegraph pole that an army truck had knocked over while backing up. In 1963, his diary was ‘discovered’ — portions had previously appeared in 1959 and 1960 in the Shenyang military region newspaper Progress (Qianjin bao 前进报 ) — and published under the sponsorship of Lin Biao, then Minister of Defence. The diary is full of entries describing his acts of selflessness, such as darning the socks of his comrades in the platoon while they slept, and of his devotion to Mao Zedong — he is known as ‘Chairman Mao’s good soldier’ — and it became an important element in the construction of Mao’s personality cult. Lei’s diary, if it is genuine — there are many doubters — reveals him to have been an ideological zealot whose love for and devotion to the Party was only exceeded by his hatred for the ‘exploiting classes’. His greatest wish, he wrote, was simply to be ‘a revolutionary screw that never rusts’. The original Lei Feng propaganda campaign was deeply ideological and focused on the inseparable link between good comradely behaviour and party loyalty.

Over the years, and in a contemporary China less focused on ideology, Lei Feng has transformed into what Tania Branigan of The Guardian has called a ‘depoliticised Good Samaritan’. On 5 March, the annual ‘Learn from Lei Feng Day’, many younger Chinese collectively donate blood or visit old people’s homes to do good deeds. In 2013, Jiaotong University commissioned a special Lei Feng badge for its students to wear. The university website said that the ‘Learn from Comrade Lei Feng’ badge should remind people to share their umbrella with fellow students caught in a downpour or to give a lift to students heading in the same direction’. In another example, a former volunteer for the Beijing Olympics indicated that while Lei Feng inspired him to take on that role, ‘being a volunteer does not simply mean helping others or doing good deeds … it has something to do with environmental protection, assisting the poor, and helping the disabled’. A billboard in the Xujiahui underground station in Shanghai encourages similar, boy scout-like behaviour: helping blind people, giving up your seat for the elderly, assisting people to cross busy roads, and making sure that lost property gets back to its rightful owner. Such anodyne, do-gooder campaigns hark back to earlier Chinese attempts to civilise people’s behaviour, such as the Nationalists’ New Life Movement of the 1930s discussed in the introduction to this volume.

More cynical members of China’s younger generations predictably have had fun with Lei Feng’s image. A silly catchy song called ‘All Northeasterners are Living Lei Fengs’ was released in 1999, with an equally silly cartoon attached to it, and went viral across the country when it was uploaded to the Internet. A popular Shanghai comedian tells how so many party officials visited an old people’s home one Lei Feng Day to help bathe and cut the hair of the residents that some old people gave up putting their clothes back on because they would only have to get undressed again for the next compulsory bath.

The years 2012 and 2013 have, nonetheless, been special ones for Lei Feng: 2012 marked the fiftieth anniversary of his death and 5 March 2013 was the fiftieth Lei Feng Day. It was on 5 March 1963 that the People’s Daily published Mao Zedong’s essay ‘Learn from Comrade Lei Feng’ (Xiang Lei Feng tongzhi xuexi 向雷锋同志学习) along with the now-ubiquitous inscription of that phrase in Mao’s distinctive calligraphy. On 1 March 2013, Liu Yunshan, the fifth-ranked member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo, President of the Central Party School and Chairman of the Central Guidance Commission for Building Spiritual Civilisation, addressed a Central Committee symposium to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Mao’s inscription. Continuing to learn from Lei Feng’s example, he insisted, would ‘advance the building of the socialist core value system and unite and inspire the entire nation in pursuing socialist morality’. The symposium declared Zhuang Shihua — a surgeon attached to the Xinjiang Armed Police Corps hospital in Ürümqi and a delegate to the Party’s Eighteenth National Congress — to be a ‘Modern-day Lei Feng’ (dangdai Lei Feng 当代雷锋). It commended him for being a doctor who had ‘successfully completed a record 58,000 operations, mostly gall bladder surgeries, and made seven breakthroughs that filled the nation’s gaps in the field … . Working in a region that is home to various ethnic minorities, the selfless doctor has greatly contributed to ethnic unity there. He often visited patients by hiking across snow-capped plateau, covering over 380,000 kilometres to date. Zhuang also donated about 46,000 yuan to his patients and provided long-term financial assistance to three poor students.’

In honour of the pair of fiftieth anniversaries, the Chinese Post Office issued a new set of stamps featuring Lei Feng’s image and Mao’s calligraphy — an event that was especially celebrated near Lei Feng’s birthplace. But three new films about Lei Feng’s life that were released for the anniversary Youthful Days (Qingchun Lei Feng 青春雷锋), The Sweet Smile (Lei Fengde weixiao 雷锋的微笑) and Lei Feng in 1959 (Lei Feng zai 1959 雷锋在 1959), despite heavy promotion, proved to be box-office flops and many screenings were cancelled. The celebrations were further dampened when eighty-two-year-old Zhang Jun, the photographer who had taken more than 200 photos of Lei Feng in 1960, suffered a heart attack while giving a speech at a Shenyang commemoration. Zhang’s photos, the core material for the propaganda campaigns, had reportedly featured in 320 exhibitions over his lifetime.

Unofficial Exemplars

If Lei Feng represents the most traditional of Communist models, the heroes of private enterprise are among the newest. Officially not even allowed to join the Communist Party before 2001 (although the numbers had been growing unofficially since the early 1990s), private entrepreneurs now make up a sizeable proportion of party members. Heroes and celebrities in their own right, they may be seen as the unofficial exemplars of contemporary China. They are promoted, not by the People’s Daily, but the likes of Fortune magazine. In 2012, the Chinese edition of Fortune published its list of the top fifteen most influential business people in China. Predictably, most of its members come from the Internet, computer and communications industries, with some representation from white goods, agriculture, finance and real estate — all industries with close links to the state sector. The list included three state employees: Wu Jinglian, the eighty-three-year-old economist at the Development Research Centre of the State Council; Zhou Xiaochuan, the governor of China’s Reserve Bank; and Li Rongrong, the former director of the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council. The top three on the list include the heads of Huawei Technologies and Lenovo Group. Most of China’s ‘most influential business people’ still have intimate relations with the party-state system — a situation often referred to as ‘crony Communism’ — and one of the stickiest problems facing the Party in its declared war on corruption.

An interesting example of the nexus between the Party and business is number two on Fortune’s list, Zhang Ruimin, the CEO of the Haier group, one of the largest white goods manufacturers in the world. An official sponsor of the Beijing Olympics, Haier has also sponsored sports organisations across the world. In Australasia, these include the Wests Tigers in the NRL, the Melbourne Nets in basketball and the New Zealand Pulse in the Trans-Tasman netball competition. A Red Guard in the Cultural Revolution, Zhang became a full party member in 1976. He initially worked for different departments of local government in Qingdao, Shandong province, including those supervising the manufacture of household appliances. In 1982, he was asked to take over a loss-making refrigerator plant. When one inspection revealed twenty percent of their new refrigerators were faulty, Zhang had his workers smash all seventy-six substandard machines with sledgehammers. This anecdote has passed into Chinese business legend, as has his comment to the distraught workers: ‘If we don’t destroy these refrigerators today, the market will shatter this enterprise in the future!’ Apparently, he still has one of the sledgehammers on display in his headquarters.

Zhang has overseen Haier’s extraordinary rise since then, while continuing to nurture his Communist Party affiliations. Since 2002, he has been an alternate member of the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth Central Committees of the Party. In 2010, he achieved apotheosis as a management guru when the Zhejiang People’s Press published The Wisdom of Zhang Ruimin (Zhang Ruimin xue shenme 张瑞敏学什么).

The Winning Apprentice

Even the People’s Daily lauds the way

… present-day China is enthusiastically embracing entrepreneurship and individualism in the context that everyone is free to pursue wealth and is able to have his dream realised through dedication and diligence. (Quoted from the paper’s English-language edition.)

This People’s Daily quotation comes from a 2009 article about China’s first business-related reality television program, Win in China (Ying zai Zhongguo 赢在中国), based on The Apprentice. Its executive producer, Wang Lifen, had held a fellowship at the Brookings Institution in Washington to study American media. The prize for winning the series was seed capital of ten million yuan, with seven million for second place and five for the other finalists; the money came from genuine investors who then owned fifty percent of the businesses formed. The other fifty percent is owned in part by the winning contestants, the TV production company, and some viewers who had voted for the winners, selected at random. For the first series, more than 3000 people put up their hands, with a final 108 selected to take part. By the third series in 2008, more than 150,000 people auditioned for the program. In the final of the first series, the guest judges were the heads of Haier and Lenovo themselves. Since then, other business reality TV shows have appeared based more closely on the original model of The Apprentice, including the Tianjin-produced Only You (Fei ni moshu 非你莫属), which became infamous in 2012 for the aggressive and humiliating questioning of contestants by judges — in one case causing the physical collapse of a contestant on screen.

Still, compared to the sort of corruption that allegedly allowed Chongqing Party Secretary Bo Xilai, for example, to imprison and torture members of the business community who did not co-operate with him, the contestants on Only You have got off lightly. The corruption that model anti-corruption workers like the marvellous ox-woodpecker-guardian angel Li Xing’ai are working to eradicate is a direct impediment to the development of healthy — and civilised — conditions for doing business, however much China has ‘embraced entrepreneurship’.

One of the contestants on Only You, a television show based on The Apprentice, collapses under the strain of severe questioning by the judges.

Source: ImagineChina

For every Liu Zhijun or Lei Zhengfu gaining financially from their official positions, there were those in business on the other side of the transaction who were also making windfall profits from official corruption. These people are not immune from prosecution. In July 2013, a businessman accused of ‘illegally raising 3.4 billion yuan and defrauding tens of thousands of investors’ by running a Ponzi scheme, Zeng Chengjie (the Western media dubbed him China’s Bernie Madoff) was executed for financial crimes. Once, however, the state media had described Zeng as ‘diligent, wise and conscientious’. His fall from grace illustrates the continuing powerful culture of exemplary categories in China. Zeng was all good, or he was all bad; he was either a hero or a villain, a figure to be held up for either praise or blame. In his consecutive roles as positive and then negative example, he was a model contemporary Chinese citizen.