Justice stands at the intersection between state and society in all of its dimensions. It is the expression of relations between the vast majority of China’s people and the relatively small coterie who govern them – the Chinese Communist Party. As more people resist the interference of power-holders in all aspects of their lives as well as the abuse of their social and economic rights, the Party has come to regard such behaviour as arising threat, an alternative source of legitimate power and justice. The collective, if often inchoate, power of the average citizens and the importance they have come to place on justice today pose direct challenges to China’s ‘red rising’ – that is the increasingly assertive party-state and its goal of ‘maintaining stability’.

Propaganda poster: ‘Everybody participate; collectively build an harmonious community.’

Source: Baidu Baike

During the years 2010-2012, China was riven by social tensions. Dysfunction in local political structures over many years fuelled a thirst for justice. While the country’s rapid rural and urban development (discussed in the previous chapter) have benefitted the national and indeed the international economies, land seizures by unscrupulous developers with the help of corrupt party-state officials have sparked public outrage, and protest. In these boom years individuals and various groups in China have increasingly resorted to collective and individual resistance – protests and other forms of overt dissent including strikes, demonstrations and riots in an effort to secure social and economic rights. Increasingly, people are expressing their anger not just about inequalities of wealth and opportunity but also inequalities that limit access to the legal system and impartial justice.

Ideology has been central to the philosophy and practice of justice throughout the history of the People’s Republic. Political rhetoric is often used to rationalize measures of social control, such as policing operations and regulations designed to modulate and manipulate social conduct. Ever since the founding of the People’s Republic, the Party has determined the state’s responses to crime and unrest – including the nature of judicial decision-making in criminal trials. As social disturbances and legal contestation have come into sharper focus in recent years a version of former Party Chairman Mao Zedong’s all-encompassing approach to social control has competed at the local level with the ‘harmonious society’ model promoted nationally since 2005.

In the lead up to the transition year of Chinese party-state power of 2012-2013, law and order became a critical arena in which both the outgoing leadership as well as the incoming contenders for ultimate power attempted to accrue political capital. In the first half of the 2000s, reformers within China’s legal system had begun to make significant headway in their efforts to create a corps of professional judges and institute a less draconian regime of punishment for criminals. Although these reforms remained largely in place in 2012, they co-existed with the increasingly egregious actions of both civil and armed police in the suppression of rising dissent. The future of the legal reforms will depend on the outcome of the leadership transition itself.

Zhou Yongkang, often referred to in the international media as China’s ‘top cop’. As the ninth member of the Standing Committee of the Communist Party’s Politburo, Zhou has overseen security forces and law enforcement agencies in recent years.

Source: Baidu Baike

Two contrasting approaches shaped the legal landscape during the post-Beijing Olympic years, 2008-2012. The first was the ‘Chongqing initiative’ or model that pursued a two-pronged policy summed up in the slogan ‘Sing Red, Strike Black’. The charismatic and mass mobilization ‘red campaigns’ of Chongqing are discussed in the preceding chapter. The ‘black’ refers to Chinese mafia-style syndicates and other criminal activity. Like many rapidly developing areas in China in which local power and economic opportunity were relatively unrestrained by suitable checks and balances, Chongqing was rife with corruption and organized crime when Bo Xilai became the municipality’s Party chief. In 2009, Bo and his security forces launched the ‘strike black’ anti-crime campaigns. Thousands were rounded up and tried for crimes including accepting bribes, other forms of economic crime, assault and murder.

While all this was happening in the south-west, Party General Secretary Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao were determining national ‘social stability’ policy settings. These policies aimed to enforce social stability at all costs; the goal was defined as consolidation of an ‘harmonious society’. In contrast to Bo Xilai’s approach, this agenda favoured what were called ‘stability maintenance operations’ – a strong police presence at rallies, protest meetings and in dealing with individual cases of disruption (real or imagined) – rather than a Mao-style mass campaign approach such as championed by Bo Xilai. Competing political camps infused political ideologies of control into justice and security agendas on both national and local levels. They did so to align themselves and their approaches with the quest for national stability/ unity – for the sake of their own political advancement. This contest over the styles of control and the kinds of justice they deliver is of crucial importance to the Party: it is at the core of it credibility as the sole source of state power and authority.

One of the egregious failures of the Hu-Wen era (2003-2012) was that the Beijing-based Party elite did not successfully build into local government operations a substantive form of oversight or moderation that could effectively – and not merely rhetorically – curb corruption and abuses of power. Over the first three decades of the post-Mao era Open Door and Reform policies initiated in 1978, apart from critical periods of popular protest such as the mass nationwide uprising of 1989, people had generally been willing to forfeit political engagement in exchange for assured social and economic rights. But the local configuration of power in villages, townships and cities across the nation is such that over recent years many millions have become increasingly aggrieved as they have seen even these rights eroded. Local power-holders sanction rapid economic development that tolerates, if not encourages, the seizure of agricultural land and allows unregulated factory production that often has serious environmental consequences. When people felt that they had exhausted all avenues of redress for the plunder of their economic and social rights mass protests have erupted.

The ‘Mass Line’ and ‘Harmonious Society’

In China the practice of and debates around law and order have been shaped by the Maoist concept of ‘social contradictions’, that is social or political activities that cause discord, crime or dissent within the ranks of ‘the people’ (that is the majority of citizens), or between the people and their enemies. Today ‘enemies’ are defined as individuals or groups suspected of destabilizing society, threatening the territorial integrity of the nation or questioning the ultimate authority of the Communist Party. These days, ‘social contradictions’ is a term often used euphemistically to describe social conflicts between the disaffected masses and the objects of their disaffection: local government officials, developers and, in some cases, company bosses.

Harmonious Society (hexie shehui 和谐社会)

The concept of the ‘harmonious society’ was originally introduced at the National People’s Congress in 2005 and is associated with Hu Jintao. It was developed into a fully blown Party resolution in 2006 that included a blueprint for social and political governance; its proclaimed goals included producing more equitable economic and social outcomes by reducing the egregious disparities in income and living conditions between China’s haves and have-nots. The mantra-like formula ‘harmonious society’ is repeated ad nauseam by officials and in the official media, but in popular usage it has acquired a negative connotation. It is often used as a satirical euphemism for the government’s efforts at maintaining stability, including censorship and the suppression of dissidents.

Chinese Internet users, who are inclined to mock all political slogans, created a slang pun on ‘harmony’: river crab (河蟹, pronounced héxiè, homophonous with ‘harmony’ or héxié). To be censored is sometimes referred to as ‘being harmonized’ or ‘being river-crabbed’, and ‘river crab’ sometimes indicates censorship.

‘Sing Red, Strike Black’ (changhong dahei 唱红打黑)

In 2009, the Chongqing Party Secretary Bo Xilai announced a campaign to revive China’s red, or revolutionary-era culture and to rein in criminal activity. This campaign went under the rubric of ‘Sing Red, Strike Black’. ‘Sing Red’ signified the need to ‘sing red [or pro-Party and patriotic] songs, read red classics [the works of Mao and other leaders], recount red stories [of the revolution and patriotic valour] and pass on [to the next generation] red maxims’. ‘Strike Black’ was short for ‘strike down social darkness and eliminate evil’, which refers to organized criminals.

As police cracked down on organized crime, restrictions were placed on TV and radio stations: reducing entertainment programs and advertising in favour of ‘red’ revolutionary programming. Mass events were organized at which tens of thousands of participants sang Mao-era songs.

The ‘strike black’ element of the campaign ensnared prominent business people, government officials and even the city’s former police chief, who was convicted and executed. While the campaign drew criticism from some liberal intellectuals and people who were persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, leftists who idealized Mao’s rule (or at least aspects of it) praised it wholeheartedly.

The movement halted abruptly following Bo Xilai’s dismissal in March 2012.

In the period 2010-2011, approximately 100,000 mass protests occurred as a result of local injustices and abuses of power. The gathering momentum of online expressions of dissatisfaction (a topic discussed also in chapters 5 and 7 in this volume) helped fuel unrest in the streets.

The nationwide social anomie was in part exacerbated by the political transition that was slowly unfolding in the lead up to the 2012-2013 renewal of Party and state leaders in Beijing. Without an open political process, a free media, or regular channels for political contestation in which differing socio-political agendas could be aired, some of the aspirants for the top jobs in China sought to bolster their political capital by demonstrating their ability to maintain ‘stability and unity’. This made the landscape of law and justice in China, hitherto dominated by a single, dominant Party ideology, contested territory.

In the Mao era (1949-78) justice in the People’s Republic was underpinned by a policy of class struggle and the use of mass trials. These events were staged not only to impose the ‘proletarian dictatorship’ but also to educate (and caution) the population at large. The mass line was essentially a means used to mobilize popular participation in national economic and revolutionary goals. For its part, ‘mass-line justice’ sought to transform the ‘diffuse and unsystematic’ ideas of the masses and meld them in ‘a concentrated and systematic way’ so as to resolve social frictions between and within classes.

In twenty-first century marketized China, such concepts of social (and overt) class contradictions belong to a different era. Today, the authorities still speak of pursuing the ‘mass line’, but this is little more than a rhetorical device, stripped of significant content or meaning. Generally, the state now asserts itself not through mass mobilizations but in the overt application of state power via vast police actions, sometimes in the form of anti-crime campaigns intended to punish ‘enemies of the masses’, that is corrupt officials and organised crime.

A propaganda poster from the Chaoyang District Government, Beijing: ‘If you, me and him are civilized, all families will live in harmony.’

Photo: Geremie R. Barmé

A more voluntarist aspect of the old mass line reappeared, however, in recent years in the form of the ‘Sing Red’ campaign mentioned earlier that aimed, through the collective experience of revolutionary and patriotic culture, to evoke and reaffirm mass unity. Bo Xilai, the Party Secretary of Chongqing who features throughout this volume, introduced and actively propagated this approach with the advice of his think tank supporters to create what has been dubbed the ‘Chongqing Model’ (for more on this see Chapter 2).

The expression ‘harmonious society’, meanwhile, has been the dominant form of official rhetoric used by the Beijing authorities to bind fractured social relations in the decade from 2002 to 2012. ‘Harmonious society’ was formulated to deal head-on with the dramatic rise in the social tensions triggered by China’s unprecedented and uneven economic development. Up until about 2007, the year prior to the Beijing Olympics, the ‘harmonious society’ strategy generally favoured a kid-glove approach to social issues, aiming to ensure greater social stability and public harmony and to present a more humane and welcoming face to the outside world.

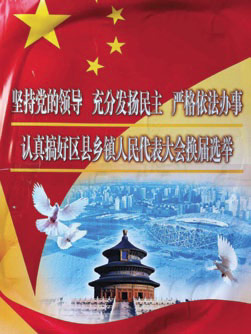

‘Insist on leadership by the Party, develop democracy to the fullest, do everything according to the law. Diligently carry out elections for representatives

at district, county, village and town levels.’

Photo: Geremie R. Barmé

Both the ‘red politics’ of the Chongqing Model and the ‘harmonious society’ strategy of Beijing shared a common presumption: that the interests of ‘the masses’ are at one with those of Party elites. In reality, over recent years the chasm between the masses and the country’s social-political elites, never inconsiderable, has only widened.

An undertaking to narrow the gap between incomes and social opportunities was written into a state plan to support the construction of the ‘harmonious society’ in the mid-2000s. But such promises were at best vague and unrealizable. After 2007, the rhetoric changed. Instead of addressing the problems and injustices, the Party leadership turned its focus on the protests and petitions these sparked among the restive masses themselves. It declared that people and groups who created social unrest, that is those who were protesting in increasing numbers against abuses of power and the disparities in wealth, should be dealt with through socalled ‘stability maintenance’ operations.

‘Stability maintenance’ (wei wen 维稳, an abbreviation of weihu shehui wending 维护社会稳定) is a catch-all term covering a range of policing methods from the crackdown on open dissent widely reported in the international media to anti-crime campaigns. Thus, after 2007, the ‘harmonious society’ was less about ‘building’ a certain kind of society and more about ‘protecting’ the status quo against those who dared to dissent through ‘stability maintenance’.

Stability and Unity (anding tuanjie 安定团结)

By 1974, as a result of nearly a decade of extreme revolutionary politics, China remained politically torn and volatile. Although he had been the ultimate progenitor of years of chaos, Mao increasingly saw the need to restore order. That year he called on Party leaders to pursue a policy of ‘stability and unity’.

Deng Xiaoping initially contested this directive on ideological grounds, but Mao overruled him by stating: ‘Stability and unity does not mean giving up class struggle’. In 1977, after Mao’s death, Deng was reinstated and became the de facto leader of the Party. ‘Stability and unity’ remained the premise for the Party’s work; Deng even stated: ‘Stability crushes everything else’ (wending yadao yiqie 稳定压倒一切). The phrase ‘stability and unity’ came to be associated with Deng, despite its early use in a campaign against him.

‘Stability crushes everything else’ was eventually replaced by the Jiang Zemin-era ‘culture of harmony’ (hehe wenhua 和合文化) and then by Hu Jintao’s ‘harmonious society’. All have aimed to preserve the hard-won social stability and political unity that dates from the start of the Reform era in late 1978.

Mass Line (qunzhong luxian 群众路线)

The ‘mass line’ was a method of leadership designed by Mao Zedong that sought to ‘learn from the masses’ in general, and the peasantry in particular, by gathering their ideas and systematizing them as a basis for social and political action.

The mass line, first articulated by Mao in 1927, was an attempt to adapt Marxist-Leninist doctrine to China’s particular socio-political conditions. The mass line was supposed to ensure that the Chinese Communist Party would run a government by the people and for the people. Mao later criticized the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin for being out of touch with the masses.

As Mao himself said:

To link oneself with the masses, one must act in accordance with the needs and wishes of the masses. All work done for the masses must start from their needs and not from the desire of any individual, however well-intentioned. It often happens that objectively the masses need a certain change, but subjectively they are not yet conscious of the need, not yet willing or determined to make the change. In such cases, we should wait patiently. We should not make the change until, through our work, most of the masses have become conscious of the need and are willing and determined to carry it out. Otherwise we shall isolate ourselves from the masses.

— ‘The United Front in Cultural Work’ (30 October 1944)

The people, and the people alone, are the motive force in the making of world history.

— ‘On Coalition Government’ (24 April 1945)

The face-off between powerful elites and aggrieved non-elites has led to a twofold crisis of confidence. On the one hand, the people have lost faith in the party-state’s ability to address issues of the abuse of power. On the other, the officials have lost confidence in the ability of political and legal institutions to ensure social stability by solving social problems through the legitimate exercise of the law. It is as if, in recent years, the party-state has lost faith in its own promise to provide institutional autonomy and the rule of law.

Mass-Line Justice: the Bo Xilai Formula

By 2010, Bo Xilai’s ‘Chongqing Model’ was for driving the conversation on issues of justice and policing, on the Internet, in communities and in the capital Beijing itself. He boldly coloured his socio-economic and justice policies red, justifying his approach as being one that ‘puts the people first’ (an update of the old Maoist slogan about ‘serving the people’). He also claimed that it a ‘necessary corrective’ to the political and economic approach laid down by Deng Xiaoping during his 1992 Tour of the South that ‘development is an inescapable necessity’ (fazhan shi ying daoli 发展是硬道理). In its place, Bo attempted to situate ‘the people’ at the centre of socio-economic policy and he proposed to do so by improving the living and working conditions of Chongqing’s millions of peasant migrant workers (nongmingong 农民工), for example providing cheap rental housing for Chongqing’s large, and economically vitally important, population of peasant migrant workers.

The other side of Bo Xilai’s policy, ‘Strike Black’, was to achieve a more ‘equitable’ distribution of justice. It was in the name of the masses that Bo pursued a much-celebrated 2009 campaign to rid Chongqing of organized criminals and their ‘protective umbrellas’ in government. He revived Mao-era tactics such as exhorting the masses to report and denounce suspected criminals. It was such strategies and the language in which they were framed that gave Bo’s anti-crime campaign the political cachet it required to distinguish his approach from that of his rivals. Although his campaign to ‘Sing Red, Strike Black’ was restricted to Chongqing, the effects were felt nationwide.

Yao Jiaxin 药家鑫

In October 2010, a twenty-one year-old junior at the Xi’an Conservatory of Music by the name of Yao Jiaxin accidentally hit Zhang Miao, a twentysix- year-old woman, with his car. Fearful that she would report his licence plate number and demand compensation, Yao stabbed the young woman to death. In the weeks that followed, Yao’s extraordinary cold-bloodedness raised the profile of the case, and rumours circulated on the Internet that he had a powerful family that would help him escape punishment. These rumours later turned out to be false. Following his arrest, Yao admitted that the reason he killed Zhang was that he assumed from her peasant-like features that she might try to take advantage of the situation and extort money from him.

For a time, Yao’s trial and appeal were one of the most talked-about issues in the Chinese media. Online opinion was overwhelmingly in favor of a death sentence. Yao was executed in June 2011.

Li Zhuang 李庄

Li Zhuang was, until recently, a Beijing-based lawyer. He became embroiled in the politics of Bo Xilai’s ‘Sing Red, Strike Black’ campaign in late 2009 when he was seen to have provided too rigorous a defence for the Chongqing crime boss Gong Gangmo. Gong claimed that he had been tortured by police, but when he recanted, police authorities accused Li Zhuang of ‘inciting a client to give false testimony.’

As a result, in January 2010, Li was himself arraigned in court and sentenced to thirty months in gaol. Immediately after the sentence was read in court, Li openly accused prosecutors of breaking a plea deal. The sentence was reduced to eighteen months on appeal. Months prior to his release in April 2011, prosecutors brought further charges that were later dropped due to a lack of evidence. Li’s case is seen as being significant as it sent a clear message to lawyers to keep their defence work in line with the political interests of Party authorities.

Li Zhuang, now free, is a frequent commentator on social affairs on his Sina Weibo microblog.

8 July 2010: the execution is announced of Wen Qiang, former head of the Municipal Judicial Bureau of Chongqing, for a number of crimes ranging from protecting organized crime and accepting bribes to rape. His conviction came as a result of the ‘Strike Black’ campaign.

Source: Chongqing Economic Times

Three corruption-related cases in Chongqing dominated national media reports on crime control in 2010 and 2011. The head of the municipal Bureau of Justice and former Deputy Police Chief, Wen Qiang, was convicted of having taken bribes in excess of 100 million yuan and was executed in 2010. The ‘Chinese mafia’ crime boss Gong Gangmo was gaoled for life for a spate of violent and economic crimes. His lawyer, Li Zhuang, became a household name when he was charged, tried and gaoled for allegedly helping his client falsify evidence. The case against Li was widely regarded by China’s legal world as a travesty of justice and a frame-up. In an open letter to his colleagues in Chongqing one of China’s most famous legal scholars, He Weifang, went so far as to say that the actions taken by Bo Xilai and the Chongqing police force against Li had set the course of the rule of law in China back thirty years.

These Chongqing dramas were hardly the only instances of badly behaved privileged urbanites that made justice news over this period. But they certainly did further erode the credibility of and community confidence in the prospects of decent governance and justice. The public also expressed outrage over the handling of less high-profile criminal cases than those involving Chongqing’s crime lords and their political cronies. Two examples outside Chongqing are the case of Yao Jiaxin and the ‘My Father is Li Gang’ incident (outlined in Chapter 5). Both involved relatively well-off young men who, having each accidentally run over and killed people, attempted to escape justice. Both cases gained instant national notoriety and demonstrate how quickly public anger can turn against individuals perceived as having used their power or status to gain unlawful or unfair political, economic or social advantage – or to escape legal sanction. These were not members of the party-state bureaucracy, or nomenclatura, but individuals of only relatively modest social status who nevertheless had taken advantage of their personal networks to evade responsibility for their actions.

Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao Maintain Stability

In March 2011, it was announced that China’s annual budget for ‘stability maintenance’ was over 650 billion yuan, a sum in excess of official figures for national defence. The news raised eyebrows both in China and abroad, even though such an escalation of police budgets and powers had been evident before the August-September 2008 Beijing Olympics. As early as 2007 the Party had begun to act against individuals who generated ‘disharmony’ by participating in or fomenting ‘mass incidents’.

The international media tends to focus on individual cases of repression of defence lawyers, grassroots human rights activists, dissident intellectuals like the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Liu Xiaobo, net activists and troublemaking artists like Ai Weiwei. The Chinese authorities’ attention, by contrast, is really concentrated on ‘mass incidents’ (qunti shijian 群体事件). A ‘mass incident’ could be anything from a sit-in, march, rally or strike to a full-blown street demonstration organised to protest against injustices or abuses of power. Such protests might involve ten people or more than 1,000 and, in some cases, over 10,000. According to Chinese reports, there has been an average of over 100,000 mass incidents annually. Many protesters are poor and vulnerable individuals. Threats to their already limited social and economic access to resources (a home or a low-paying job) can easily spark an emotional confrontation with the responsible authorities. Relatively benign incidents, easily resolved but allowed to fester by local authorities, frequently escalate from ‘small disturbances’ (xiao nao 小闹) to become ‘major disturbances’ (da nao 大闹). Such disturbances – protests – are almost invariably directed against government officials, local developers or businesses. The situation, paradoxically, benefits the central authorities. The strategy of ‘localising grievances while insulating the Centre’ successfully encourages a perception that the central government is sympathetic in principle to the aggrieved, poor and vulnerable people involved in such protests.

Peasant Workers

(nongmingong 农民工, often shortened to mingong 民工)

A mingong or peasant worker is a person whose hukou (household registration, see Chapter 2) identifies him or her as a farmer but who has migrated, usually to a city, in search of work. A Survey of China’s Peasant Workers (Zhongguo mingong diaocha 中国民工调查), a book published in 2005, claimed that there were more than 300 million mingong in China, including the children of mingong growing up in cities but still tied to their home village by their household registration.

Mingong are typically people with relatively little education who work on construction sites and in factories. In cities like Beijing and Shanghai, many university graduates from rural areas who have failed to obtain an urban hukou are also officially registered as mingong.

A less politically correct alternative to mingong is the term mangliu 盲流, literally ‘blind floaters’, one which suggests the unchecked flow of rural poor into the cities. The pejorative use of mingong by urbanites has given the term a derogatory meaning, and a number of alternatives have emerged, including ‘new city resident’ (xinshimin 新市民) and ‘new contract worker’ (xinxing hetong gongren 新型合同工人).

Around sixty-five percent of China’s mass incidents relate to the misappropriation of agricultural land. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences estimates that fifty million farmers had their land seized in 2010, with that figure increasing annually at a rate of three million. Increasingly, people are also protesting en masse in response to environmental threats to their health, livelihood and homes by polluting industries and government actions. A typical example is the October 2010 Wenchang Incident in Hainan province. Thousands of people protested against the failure of local government officials to notify them before releasing the waters of a local reservoir inundating hundreds of properties. In one of the largest protests of 2011, tens of thousands of residents in the northern city of Dalian forced the authorities to close a paraxylene chemical plant. A storm had damaged the dyke around the plant, sparking fears that paraxylene made at the plant could spill into the water system and inflict enormous damage. Mass protests like these occur because people do not have effective, conventional dispute-resolution mechanisms at their disposal. As the commentator Tang Hao put it: ‘When local governments use unconventional methods to build polluting projects, the public is forced to resort to unconventional means to protect their interests.’

Other incidents can be sparked by a single individual taking action against a perceived injustice, such as in the case of the October 2010 tax riot in Huzhou city in Zheijiang province on China’s south-east coast. An argument between a local tax collector and a textile business owner quickly escalated into a protest involving hundreds of people enraged at local tax hikes.

Main entrance of the Supreme People’s Court, Beijing, which is located in the former Foreign Legation Quarter.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

A courtroom, Supreme People’s Court, Beijing. The court boasts 340 judges.

Source: flickr/Seth Nelson

Stone lions, which traditionally stood in front of imperial government buildings adorn the entrance to the Supreme People’s Court, Beijing.

Source: Anthony Ellwood-Russell

Accidents or violence in which ordinary people were victims and local officials then perpetrators led to particularly explosive incidents. The Kunming riot of March 2010 was sparked when urban management officers (chengshi guanli xingzheng zhifa renyuan 城市管理行政执法人员, chengguan for short; a particularly unpopular form of roadside bureaucrat) tipped over a tricycle cart being ridden by a sixty-yearold female peddler, resulting in her death. Hundreds of witnesses to the accident surrounded the government vehicle and beat up the officers.

Stability Maintenance (wei wen 维稳)

Since 2005, the Chinese government has allocated vast amounts of money and resources to quash organized resistance to its authority. Revolutions overseas, the growing use of mobile communications and digital networking, as well as labour conflicts and ethnic unrest have all had an impact on China’s stability maintenance campaign. Added to this is an awareness that local corruption and malfeasance by party-state officials have generated resentment and protest, that there are limited avenues for complaint or redress and that rapid economic development has generated serious social inequalities.

The overall strategy of using police force to maintain social stability and to enforce the official version of social harmony is a campaign known by the expression ‘wei wen’, a shorthand for weihu shehui wending 维护社会稳定, or ‘maintain social stability’. Charged with ‘maintaining stability’ are local police in public security bureaus across the nation and parapolice belonging to the military’s expanding contingent of People’s Armed Police (PAP). Stability maintenance incorporates ‘preventative’ activities such as building extensive CCTV surveillance networks in major cities such as Chongqing, as well as maintaining a strong police, military police and private security presence at protests and rallies. Stability maintenance also involves Internet censorship, paid informants, security contractors, the harassment of activists, and neighborhood watch-dog groups.

‘Wei wen’ was a much-used term in March 2011, following online calls for a ‘Jasmine Revolution’ in China. The term and the execution of related policies are associated closely with Zhou Yongkang, a key member of the Party’s leading Politburo and head of China’s security services slated for retirement in late 2012.

Rights Protection (wei quan 维权)

Wei quan is a shortening of the expression weihu hefa quanyi 维护合法权益, ‘protect legal rights’. It is a term that came into use in the early 2000s to refer to a grassroots network of activists and lawyers who have tried to defend the rights of Chinese citizens. Despite harsh restrictions and persecution by the government, some lawyers and intellectuals persisted in organizing demonstrations, writing letters of appeal, pushing reform through petitions and the media, and defending victims. They are known as wei quan or rights activists.

Government reactions to these grassroots activities have at times been extremely harsh, with reported instances of detainment and torture. Use of the Internet, including blocked websites like Twitter, by activists has unnerved the government, and it is not unusual for prominent rights activists to be ‘invited to drink tea’ (qing hecha 请喝茶), that is, to attend a compulsory meeting with security officers to explain postings on Twitter or other activities over a seemingly innocent cup of tea.

The most dramatic and influential mass incident in recent years occurred in Wukan township in Guangdong province, previously mentioned in Chapter 2. Starting out as a protest against official land grabs and the illegal sale of agricultural land to developers, a demonstration in late 2011 quickly morphed into China’s largest local uprising in recent memory. The vast majority of the town’s residents crowded into the streets and pitted themselves against local Party and policing authorities. After years of economic deprivation at the hands of illegal land dealers who were in business with local Party chiefs, residents rose up, took to the streets and stormed government offices in their thousands. When one of the protest leaders who had been taken into custody by police died, the incident escalated further. The township was placed under siege and food and fuel supplies were cut off by local and provincial public security and military police.

Inner Mongolia Riots, May 2011

One of the most noteworthy mass demonstrations in 2011 occurred in Inner Mongolia, a Chinese territory bordering Mongolia. The situation was sparked by the death of an ethnic Mongolian herder named Merger who, on 10 May, tried to stop a convoy of coal trucks that had been damaging grazing pastures and harming goats by driving through the grasslands. Witnesses said that a driver deliberately ran over the herder. The incident spurred over a thousand demonstrators, including some students, to take to the streets in Xilinhot in the biggest show of people power in Inner Mongolia in over twenty years.

In a situation with some parallels in Xinjiang and Tibet, many ethnic Mongolians blame Han-owned companies operating mines in Inner Mongolia for not sharing their wealth with the indigenous population. The riots were quelled only when paramilitary police came out in force against the protesters. The driver of the truck was tried for homicide, sentenced to death and executed. The provincial government also announced new rules concerning grassland protection.

Demonstrations in Weng’an, Guizhou province, after allegations of a cover-up connected with a girl’s rape and murder turned violent.

Source: Myspace.cn, Zonaeuropa.com

Throughout December 2011, the plight of Wukan attracted national attention. Sensing an opportunity to present an alternative to both Bo Xilai’s red campaigns and the Hu-Wen leadership’s bully-boy crackdown style, the Guangdong provincial Party leader and nemesis of Bo Xilai, Wang Yang, turned events to his own political advantage. He sent in his deputy to negotiate with the protesters. When, at the end of the month, Wang promised that the local officials would be brought to justice and fresh (and free) local elections would be held both police and protesters backed down. Wang Yang declared a victory and claimed that this was a new model – the ‘Wukan approach’ – to resolving social disputes.

This mix of politicking, mass incidents and stability maintenance activities in the post-Olympic years was made more volatile by a series of ‘disappearances’ of civil rights lawyers, men and women known as advocates of ‘rights defence’, or wei quan in Chinese. The lawyers Teng Biao, Jiang Tianyong and Tang Jitian, who met to talk about the case of blind civil rights activist Chen Guangcheng, then under house arrest, were inexplicably ‘disappeared’ by police. They eventually reappeared and were subsequently all placed under strict surveillance and then house arrest. These arrests and disappearances coincided with Chinese protests inspired by the 2010-2011 Middle East and North Africa protests (discussed in Chapter 5).

Police detained the Beijing civil rights lawyer Ni Yulan, a woman with a long history of conflict with the security forces, for various lengths of time during 2010-2011 for her protests and defence work on behalf of people who had been forcibly evicted from their homes to make way for demolitions. In 2009, she was under detention for nine months and denied contact with her family. In April 2011, police took Ni and her husband into custody again for ‘creating a social disturbance’. Later in July that year, she was additionally charged with fraud for allegedly claiming that she was a lawyer so as to win sympathy for her case and for financial gain. On 10 April 2012, Ni was convicted on both charges and sentenced to two years and eight months imprisonment. Her husband, Gong Jiqin, was also convicted of ‘creating a social disturbance’ and sentenced to two years in prison. Others, such as the rights lawyer, Jiang Tianyong, who disappeared for two months from February 2011, later spoke to the press about having been tortured while in custody. The veteran activist Zhu Yufu, detained in March 2011, was arrested again the following month on charges of inciting the subversion of state power. Some were so intimidated by the authorities that they declined to comment publicly on their disappearance and periods of detention. The list of lawyers disappeared and detained in recent years also includes Tang Jitian and Liu Shihui, both of whom were whisked away by security personnel. Tang Jitian remained under house arrest until the end of 2011. He was reportedly sent back to his hometown in the north-eastern province of Jilin seriously ill, having contracted tuberculosis while in detention. Police took away the intellectual dissident Xu Zhiyong in May, while Gao Zhisheng, one of China’s most famous rights lawyers who had, among other things, also defended Falong Gong adherents was still missing at the end of the year.

Chen Guangcheng 陈光诚

Chen Guangcheng is China’s most recognized legal activist, sometimes referred to as a ‘barefoot lawyer’ after the ‘barefoot doctors’ of the Cultural Revolution era who served people outside formal state structures. The self-taught blind lawyer’s fame dates from the mid-2000s when he mounted legal challenges against local authorities in Linyi, Shandong province, who forced late-term abortions and sterilizations on local women in order to comply with national one-child policy quotas. Chen was gaoled for four years and three months on charges of ‘damaging property and organising a mob to disturb traffic’. After his release in September 2010, he and his family were immediately placed under house arrest.

In February 2011, after a home video illustrating the harsh conditions of Chen and his family’s confinement was released on the Internet, his wife reported that their house was invaded by over seventy public security personnel and that they were badly beaten. Thirtyodd supporters attempted to draw attention to their plight by visiting their village in late 2011, but dozens of security personnel set upon them and beat them as well. Other would-be visitors include journalists, European diplomats, lawyers, intellectuals and the Hollywood actor Christian Bale. None managed to evade local toughs to see Chen.

Chen’s predicament attracted widespread support from bloggers in China and human rights organizations in the West. Yet, as leading legal scholar Jerome Cohen asserts: ‘Chen Guangcheng never saw himself as a “troublemaker” bent on damaging social stability and harmony. Indeed, he wanted to improve stability and harmony by using legal institutions to process social grievances in an orderly way as prescribed by law. His only mistake was to accept the law as it was written, as a true believer in the power and promise of China’s legal reforms.’

In late April 2012, Chen dramatically escaped from his hometown of Linyi and travelled to Beijing where, with the help of supporters, he found temporary refuge in the American Embassy. After some days he was transferred to a local hospital where he was treated for injuries sustained during his flight. In May, Chen was allowed to travel overseas with his immediate family to pursue his legal studies in New York.

The blind lawyer Chen Guangcheng, now the country’s most prominent rights activist, ran afoul of local police when he helped people protesting against forced late abortions. His disappearance became a cause célèbre among rights-conscious citizens and a focus of international attention on China’s human rights record. In May 2012, he dramatically escaped house arrest in rural Shandong province, travelled to Beijing and eventually was allowed to leave China with his immediate family to pursue legal studies in New York.

Conclusion

Wei wen (stability maintenance) and wei quan (rights protection) are concepts that are now at the forefront of China’s ‘law and order’ agenda. Law is the subject of widespread and intense contention in China today. Events of recent years suggest that the ‘everything else’ in Deng Xiaoping’s 1980s’ maxim ‘Stability crushes everything else’ (wending yadao yiqie 稳定压倒一 切) includes the law as well. Overall, the authorities favour striking down with brute police force any social activity that is deemed to threaten stability. The definition of what exactly constitutes ‘stability-threatening’ activities has expanded with the intensification of political infighting within the upper echelons of the Party and state mechanisms. The crackdown on threats to ‘stability’ appears to serve both as a prerequisite for a Harmonious China and a means of shoring up the very future of the Party’s hold on national power.

Stability and unity have long been core political concerns in China from the Maoist era ‘stability and unity’ through to the present. Confronted by increased public dissent, stability and unity have once more become the dual principles supporting the Party-dominated legal system and dominating its approach to governing a nation that is experiencing exacerbated conflict between various elites and average citizens. The ‘social contradictions’ (to use the Maoist vocabulary), that the authorities still favour, at the heart of China’s justice landscape, show that the main tension in the country is not between the authorities and a few rogue dissidents, but between China’s ultimate interest group – the Party – and a building source of opposition: the people themselves.