Under what conditions does China terminate politically motivated barriers to trade? In August 2023, China announced it would remove tariffs on Australian barley that were imposed amid bilateral tensions in May 2020. The removal was widely celebrated for enabling the resumption of a trade that had been worth up to US$1 billion annually. Barley was one of the most prominent of at least nine Australian export commodities targeted by China in an apparent sanctions campaign. While barriers on barley and five other commodities have since been removed, three others remain in place, most notably for Australian bottled wine.

One possible explanation for the progress on barley focuses on foreign policy drivers. The barriers may have been removed due to warming bilateral relations under a new Australian government and a transition to a bargaining phase in the relationship. Another possibility is that Beijing dismantled the tariffs to avoid the potential reputational costs that might stem from the public release of a panel report adverse to China by the World Trade Organization (WTO). Here, we consider the logic of these two arguments, and introduce a third explanation that is largely missing from current analyses: the vested interests of groups within China, both government and non-government, and especially industry associations.

Examining the factors driving the removal of the barriers to Australian barley imports provides insight into a wider question which has received scant attention: when and why China removes sanctions. Although a burgeoning scholarly literature examines the termination of Western economic sanctions, it has not considered China. New insights on this issue may have significant policy implications. Most immediately, they are relevant to ongoing negotiations about the removal of China’s barriers on Australian wine. Many expect that the ‘template’ used in the barley negotiations — combining warming diplomatic relations with the concession of withdrawing a WTO case — will be successfully applied a second time. This appears to be playing out at the time of writing. On the back of some recent Australian decisions that may have sweetened the deal, Beijing has agreed to conduct a five-month review of its wine tariffs, and Canberra has temporarily suspended its WTO case. Unlike the case for barley, however, Beijing’s review may be complicated by substantially different underlying domestic political economy dynamics in the wine industry which could well determine whether the tariffs ultimately stand or fall.

The Imposition and Removal of the Barley Tariffs

The origins of China’s barriers on Australian barley go back to 2018. In October that year, the China Chamber of International Commerce (CCIC, 中国国际商会) requested that the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM, 商务部) investigate the dumping of Australian barley on the Chinese market. MOFCOM began its investigation in November. On 28 May 2020, after China-Australia relations had slipped into free fall, MOFCOM handed down its ruling and applied tariffs of 80.5 percent (73.6 percent anti-dumping, 6.9 percent anti-subsidy) on the import of Australian barley. The barriers reduced a trade of US$1 billion in 2018 to zero in 2021.

Against the advice of some commentators, the then centre-right Coalition government took the matter to the WTO dispute settlement system in December 2020. After two and a half years of deliberation, the WTO issued its draft panel report confidentially to the parties. This appeared to expedite bilateral negotiations for a resumption of trade, where Australia agreed to suspend its WTO complaint in April 2023 while MOFCOM undertook to conduct a three-month review of its tariffs. After extending the review to four months, China removed the barriers in August 2023. The WTO case was subsequently settled and within weeks large shipments of barley set sail from Australia for China.

What enabled this to happen?

Explanation One: Warming Bilateral Relations

The first explanation focuses on the state of the bilateral relationship between Australia and China. If imposition of the barriers, or at least a failure to negotiate their removal, stemmed from a range of political grievances on the part of Beijing, something was needed to enable a warming of the relationship. In this case, the election of a centre-left Labor government in May 2022 created the opportunity for both sides to move beyond positions hardened over the previous two years, first to resume high-level talks (previously rebuffed by Beijing) and later to negotiate the tariff’s removal. Critical of their Coalition predecessors’ rhetorical hostility toward China, the Labor government under Anthony Albanese stressed a change in tone even as it made clear there was no change in underlying interests. The goal was to ‘stabilise’ the relationship without making substantive concessions on any of the grievances believed to be motivating China’s sanctions. Canberra has, however, refrained from adopting new policies that may have been seen by Beijing as provocative, and which would have disrupted relations and the resolution of the trade disputes. A change in government and tone, and the resulting resumption of high-level contact, were likely major factors in causing Beijing to remove sanctions. However, the stabilisation of the political relationship alone cannot explain the removal’s timing and sequencing, nor does it provide confidence that the remaining barriers will be removed.

Explanation Two: the WTO Dispute and Aversion to Hypocrisy Costs

A second explanation is specific to barley itself and relates to the confidential draft panel report that was released to the Chinese and Australian governments shortly before the parties announced the suspension of the WTO dispute and Beijing’s review of the duties. The content of the draft report is not known and unlikely ever to be released. However, the decision was likely favourable to Australia due to significant weaknesses in China’s arguments that Australia had been dumping barley on its market.[1]

This explanation, also rooted in foreign policy logics, attributes Beijing’s removal of the barriers to the impending adverse decision. But why would the Chinese government be so reluctant for the panel report to be released? After all, China has lost WTO disputes in the past.

One possibility is that policymakers were particularly sensitive about this case given it related to measures which had openly been characterised as coercive sanctions. Although China is alleged to have deployed economic coercion in multiple cases over the past two decades, none of the underlying measures have ever been formally ruled upon by the WTO. The only case to come close — one concerning Canadian canola — was also resolved via negotiation before a panel report was issued.

The panel report would not have ruled on whether China’s measures were ‘coercive’ or ‘sanctions’, but rather likely presented a detailed critique of the compatibility of China’s approach with WTO anti-dumping rules. Nevertheless, Beijing may have wished to avoid a formal rebuke of its measures, which would give even more ammunition to critics arguing that the tariffs were ‘blatant economic coercion’, rather than legitimate trade measures. In other words, it may have sought to avoid ‘hypocrisy costs’. Chinese officials have annually denounced the use of sanctions — so-called ‘unilateral coercive measures’ — as a violation of international law at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) and other international forums since the 1990s. Policymakers may have had concerns that to be seen to be using sanctions might damage China’s credibility and reputation in world politics (especially with states who sign onto its anti-sanction UNGA resolutions).

According to this explanation, the draft WTO panel report created the space for a negotiated solution. It generated additional incentive for Beijing to find an alternative and avoid a formal and public ruling against it, thereby aligning with the goals of Australian industry and government to resume exports as soon as possible. Both sides preferred an outcome in which barriers were amicably removed.

One might think this explanation would generate optimism about wine, given Beijing agreed to conduct a similar review in tandem with Australia suspending its WTO case. However, it is possible that leverage from the WTO ruling alone was insufficient in achieving this outcome for barley, as we explain in the next section.

A Third Factor: Domestic Drivers of China’s Barrier Imposition and Removal

One factor that is often overlooked in analyses of China’s use of politically motivated trade barriers is the role of domestic interest groups and domestic policy objectives. As we have argued elsewhere, these factors are key to understanding the logic of the sanctions imposed on Australia. Likewise, they may help explain their removal.

The Imposition of Barriers on Barley

Policymakers: While China’s barley tariffs may have been partly motivated by a coercive objective when they were imposed in 2020, the original 2018 anti-dumping investigation was driven by agricultural protectionism. In particular, as revealed in legal case documents and other substantive reports on the issue, Chinese policymakers were acutely concerned with issues of food security or the ‘choke point’ 卡脖子 in China’s barley supply.

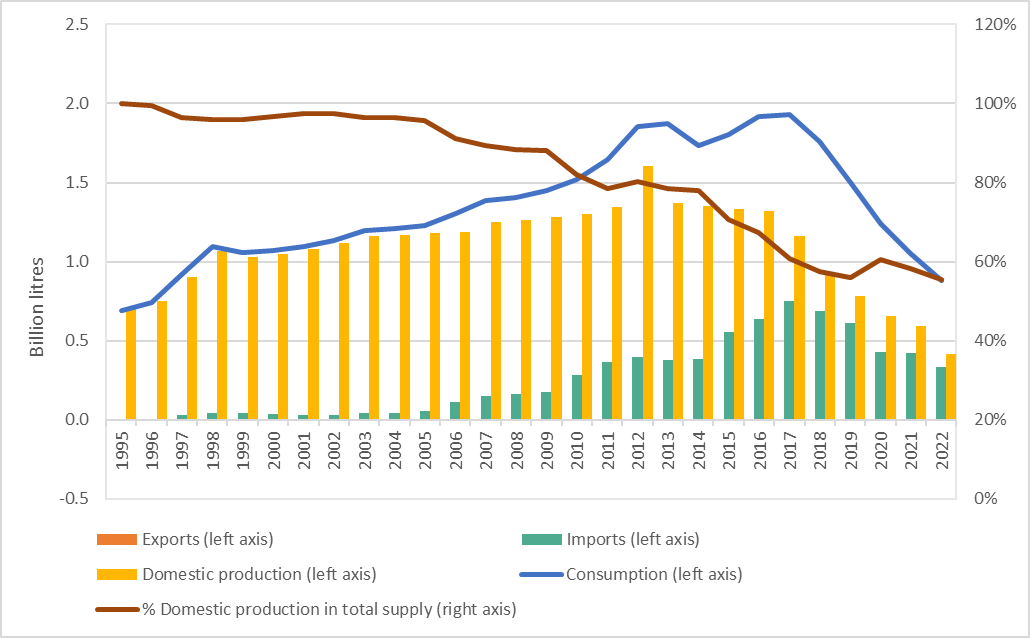

From a peak in the mid-1990s, China’s domestic barley production has undergone a long-term decline. By the period of anti-dumping investigation (2017–18), domestic supply accounted for an exceptionally low 11 percent of total barley supply. At the same time, barley imports for brewing and livestock feed accelerated, especially after 2015, with Australian companies accounting for 75 percent of all imports in some years (Figure 1). Chinese officials argued the imports led to losses in farmers’ incomes in the less developed areas of China where most barley is grown.

Figure 1. China’s barley balance, 1992-2022. Source: China Rural Statistical Yearbook, UNComtrade. All data three-year rolling averages to first data point.

The barriers appear designed to arrest these trends, driven by a range of party and state units that have an interest in food security, including the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA, 农业农村部), which assisted with the investigation.

Industry associations: Like other products, barley is grown both as an agricultural commodity and an industrial input (for brewing and livestock feed). This brings into competition sectoral interests which need to be adjudicated at a higher level. Industry associations and chambers of commerce are key players, both as representatives of their industries and conduits for the interests of the party-state.

While there is an array of industry organisations in China, the more established and influential organisations are a vestige of the central planning era, where government departments with specialised economic functions managed the operations of state-owned enterprises under their control. During administrative reforms in the 1990s, many specialised economic departments were devolved to become industry associations, comprised of enterprise members that pay membership fees for representation and services. Reforms starting in 2016 and implemented through to 2019 aimed to further administratively decouple associations and chambers of commerce from the party-state, with caveats. The key powers of party-building in associations were to be centralised and led by the Party Committee of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC, 国务院国有资产监督管理委员会), while foreign affairs were more clearly placed within the purview of the relevant (party-state) organs. A framework of state corporatism has been used to describe the ties that bind the party-state to associations and their enterprise members.

Barley provides an interesting case study in industry representation. Barley is grown in China by a multitude of individual households not represented by any industry organisation and so, by default, by government. Jurisdiction over barley production and farmer incomes from agricultural activities like barley lies with MARA. The ministry has long been concerned about China’s balance of production, consumption, and trade for barley.

Government units rarely make anti-dumping applications.[2] The organisation chosen to apply for the dumping investigation on Australian barley was the China Chamber of International Commerce (CCOIC), which has a mandate to represent the interests of Chinese enterprises in international trade and investment. CCOIC falls under the umbrella of the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT, 中国国际贸易促进委员).[3] CCPIT has a vast network of branches within China, a legal affairs department and a network of overseas law firms used for dealing with anti-dumping, subsidy and safeguard issues. It also runs the Economic and Trade Friction Early Warning System 中国国际贸易促进委员会经贸摩擦预警管理系统, which includes an international agricultural branch 中国国际商会农业行业经贸摩擦预警中心.

While the CCOIC notionally represents enterprises with foreign interests, the barriers on Australian barley are contrary to the interests of enterprises that use it for brewing and livestock feed. This is particularly the case for beer brewers that are members of the China Alcoholic Drinks Association (CADA中国酒业协会). CADA has origins as a department within the former Ministry (and then Bureau) of Light Industry before being moved into SASAC. It gained more administrative independence in the 2016–19 association reforms but retains links to the party-state.

CADA has been a participant in at least five international trade cases, either to support trade barriers (Australian wine, EU wine, US distillers’ grains) or oppose them (Australian barley, US sorghum). The differing positions reflect differences in the characteristics of alcoholic drinks including the inputs and outputs used in manufacturing and the relationship with adjacent products (ethanol and various livestock feeds). Different interests are expressed through branches within CADA, representing at least eight types of alcohol including baijiu, beer and wine. Barley is of primary concern to the CADA Beer Sub-Association (CBSA, 中国酒业协会啤酒分会) and the Beer Raw Material Expert Committee 中国酒业协会啤酒原料专业委员会. With seventy-three members, CBSA is powerful and has a strong interest in maintaining supplies of Australia’s malting barley. The attraction of Chinese brewers to Australian barley was not just access to consistent supplies of high-quality malting barley, but also access to a lower-priced grade of barley (‘Fair Average Quality’) permitted under China’s food laws for use in food (including beer) rather than being relegated to feed use.

CBSA made a forceful submission against the tariffs on Australian barley in the initial anti-dumping investigation in 2020, but to no avail. Policymakers concerned with agriculture and food security and the foreign policy preferences of the central government held sway in the initial round leading to the imposition of barriers. There was no prospect for an early reversal in 2020–22, a period of high tensions from COVID-19, strained international relations, the dual circulation policy to promote self-reliance and heightened concerns about food security, including for non-staple foods.

The Removal of Barriers on Barley

For Chinese policymakers, the tariffs had generated mixed success by 2023. As shown for the period 2020-22 in Figure 1, the tariffs successfully stopped Australian barley imports, forcing brewers and livestock companies to diversify inputs to other sources (Argentina, France, Canada, Ukraine). However, total imports in the period increased significantly, mainly for livestock feed. The trade barriers on Australian barley did not in themselves provide the protection that would generate an increase in Chinese barley production. China did however use the period to pursue new domestic policy measures including breeding, research and revised industry standards as well as the building of new barley production areas for breweries in China.[4]

Official statistics report a doubling of Chinese barley production over the period in which Australian barley was blocked (2019 to 2022) but this is a statistical quirk. From 2020 onwards, reporting on Chinese barley production (damai 大麦) included a different variety, highland barley (qingke 青稞) grown in Tibet, Sichuan, Yunnan and Qinghai: this doubled the reported planted area and production of ‘barley’. Nevertheless, with increased reported domestic production and diversification away from Australian barley, policymakers may have concluded that the barriers had served their purpose. Accordingly, when discussion of relaxing the barriers occurred in 2023, there could be expected to have been less resistance from interests within the Chinese party-state.

Simultaneously, domestic industry groups continued their opposition to the barriers. In fact, a submission made by CBSA earlier in the year became the centrepiece of the MOFCOM review. The submission argued China’s domestic barley production programs were unsuccessful and that, with the barriers in place, international supplies were expensive, inconsistent and did not meet requirements, all of which hurt the viability of Chinese beer companies. It also argued the tariffs were counter-productive to China’s own policy objectives in three areas: industrial upgrading and international competitiveness; increasing consumer confidence and spending; and meeting national standards (guobiao 国标) on beer and malting barley. The MOFCOM ruling to drop the barriers also included consideration of submissions from the China Feed Industry Association and Australian industry organisations. Chinese industry groups have similarly been active in government decisions to drop barriers on US sorghum and on lucerne, an item subject to China-US tariff escalations from 2018.

To sum up, in 2020, opposition to the barriers on Australian barley from domestic industry groups was overridden by the preferences of the central government and parts of the Chinese bureaucracy that favoured the introduction of the tariffs — either to achieve domestic agricultural policy objectives, or foreign policy objectives vis-à-vis Australia. By 2023, there was a realignment of interests in favour of the removal of the barriers, which helps to explain when and why the tariffs were dropped.

Implications for Australian Wine

The three conditions that allowed for the lifting of barriers on Australian barley — improved bilateral relations, leverage from WTO proceedings, and an alignment of industry and policy interests in China — provide some guidance on prospects for a similar outcome for Australian wine, on which China has applied similar anti-dumping tariffs. Certainly, negotiations are occurring within a similarly conciliatory bilateral environment. Moreover, given China’s case for imposing tariffs on wine appears even more tenuous than barley, the recently issued confidential draft panel report may motivate Beijing to settle if it is deemed to raise the spectre of hypocrisy costs.

However, unlike barley, there is no alignment of domestic interests in China against the barriers on wine. To the contrary, both industry associations and industry-oriented policymakers have vested interests in continuing the ban.

In the case of barley, the users of Australian product had close links to the state system and a strong stake in the resumption of the trade. But the buyers of Australian wine — importers, retailers and consumers — are not an organised group. Wine is also a luxury product that is not a priority for the party-state.

China’s wine growers, meanwhile, are in an influential position. China has for many years sought to develop a large domestic wine sector as a pillar industry with high potential for value-adding, to raise farmer incomes including in rural and undeveloped areas with grape-growing potential (Ningxia, Xinjiang and Gansu) and to promote ‘ecological’ land use and eco-tourism. Importantly, Chinese wineries are represented by an established industry organisation that falls under the same parent association that opposed the barriers on Australian barley — CADA — but a different branch, the CADA Wine Sub-Association (CWSA, 中国酒业协会葡萄酒分会). CWSA — which comprised 119 domestic wineries in 2022 — was the applicant in the investigation into the dumping of Australian wine and compiled the information for the case. In the lead-up to the investigation, the association said that imports were ‘robbing’ Chinese wineries of the domestic market, especially in the higher-value, cold-weather reds. Thus, unlike the breweries of the CBSA that benefit from Australian barley imports, the wineries of the CWSA compete with Australian wine imports and have an interest in establishing and maintaining the barriers.

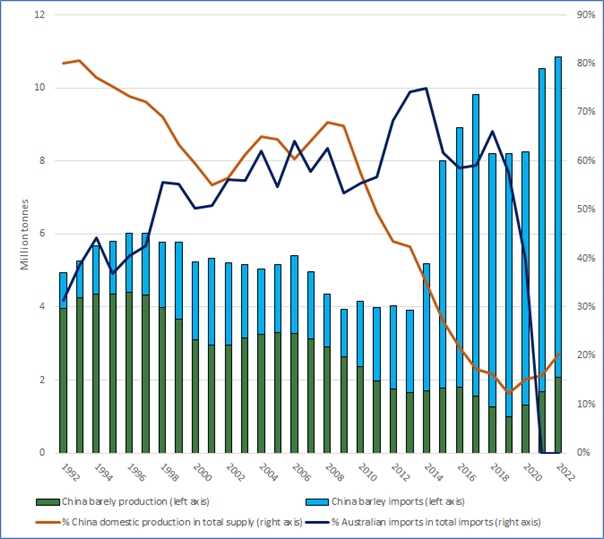

The barriers on Australian wine may not have fully allayed the concerns of Chinese industry and policymakers. Chinese wine production and consumption continued to decline in 2022 and the proportion of domestic production in total supply decreased (to 54 percent, see Figure 2). China’s Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao 王文涛 relayed concerns about the production and profitability of the Chinese wine industry as a potential obstacle to his Australian counterpart in discussions about lifting the trade barriers on wine. The potential for this to be a snag was also reflected in a cautious statement from the peak Australian industry group earlier in the year. As a way of addressing the concerns of Chinese industry and interest groups, the largest Australian exporter of wines to China entered into a joint venture in 2022 to produce Australian wine in China. The venture involves an agreement with CWSA, which sees the venture as an opportunity to transfer expertise and build China’s domestic industry.

Nevertheless, the process used to resolve the barriers on Australian barley appears under way for wine. Following the circulation of the WTO panel’s draft report on the wine dispute in October, China and Australia reached an agreement to suspend the panel while Beijing conducts a five-month review of its barriers. It is unclear where the review will land, though the expectation in Canberra on the eve of Prime Minister Albanese’s visit to Beijing in early November was for a favourable outcome. Chinese policymakers may again wish to avoid a potentially adverse WTO ruling and signal their commitment to improving the bilateral relationship. However, it may also be possible that the relationship is sufficiently ‘stabilised’ and instead in a ‘bargaining’ phase, with Beijing therefore adopting a more transactional logic where it looks to extract concessions from Canberra as quid pro quo.

One possible concession is closing a separate WTO dispute with Australia. In September it was reported that Canberra had rejected a proposed ‘package deal’ in which the wine barriers would be removed if Australia dropped anti-dumping duties it had earlier imposed on Chinese wind towers. A statement from China’s Ministry of Commerce in October, however, linked the new wine review to progress on that exact issue. Canberra denied this linkage, and anti-dumping duties are normally determined by an independent Anti-Dumping Commission that would not consider foreign policy interests in its decision. However, even if coincidental, the timing is hard to ignore — the commission released a preliminary report indicating a willingness to let the wind tower duties expire in the same week that Canberra decided not to cancel a lease held by a Chinese company over the port of Darwin, just prior to the announcement of the deal on wine. Furthermore, the week prior Australian citizen Cheng Lei had been allowed to return to Australia following three years in detention. Both sides pocketing ‘wins’ in the month prior to the first visit by an Australian prime minister in seven years speaks to a new phase in the relationship.

At the same time, unlike the barley case, the fact that there remains robust support for the wine barriers within China suggests the policy calculus is more complex. The fact that the wine review period is longer than that for barley might suggest Beijing anticipates a longer internal debate to reconcile unaligned interests, although it may also be designed to coincide with the expiration of the wind tower duties. It may be that domestic concerns are ultimately overruled, not merely by the shadow of a potentially adverse panel report, but a broader deal in an increasingly transactional relationship. In the end, if China does eventually remove the barriers, it will indicate the prioritisation of foreign policy goals and other equities over the preferences of the affected domestic industry and interest groups.

Broader Implications

It is well-recognised that domestic interest groups play an important role in trade formation, processes, and the resolution of trade conflicts. While this is borne out in the case of China-Australian barley and wine, analysis of interest group representation has largely been absent from commentary both inside and outside of China on Beijing’s politically motivated trade barriers. Such analysis can be challenging given the sprawling and opaque nature of party-state and societal linkages in the Chinese ‘leviathan’, but is nevertheless crucial for informed public debate.

More generally, our analysis has implications both for policy and emerging research on the political economy of China’s power in world politics. Concerned about China’s apparent use of international trade as a ‘weapon’, several governments have recently announced plans to coordinate their responses to Beijing’s behaviour. If these coalitions are serious about influencing when and how China uses different international economic policies, they need to pay attention to the domestic micro-foundations that underpin them.

Since the Australia episode, China has continued to impose trade restrictions during political disputes. Notable instances have involved Lithuania, Taiwan and Japan. In each case, as with Australia, governments have looked to WTO dispute settlement as a mechanism to have the barriers removed. Brussels, Taipei and Tokyo should carefully study the domestic politics behind the when, how, and why of China’s removal of barriers in earlier cases — including those involving Australian barley and wine — and look for any parallels that could help them resolve their own disputes.

In terms of research, our findings illustrate the importance of exploring the mechanics and consequences of ‘fragmented authoritarianism’ in the trade domain. It is well understood that the Chinese party-state is not unitary — even in the Xi era. But there remains considerable scope to further illuminate the mechanisms and conditions by which domestic interest groups shape China’s international economic policies.

The authors are grateful to Pru Gordon, Benjamin Herscovitch and Paul Hubbard for helpful comments.

Notes

[1] Such as using the price of Australian shipments to Egypt — a very minor export market — to determine the ‘normal value’ of Australian barley, and the claim that Australian barley imports damaged Chinese barley production, even though it had been in decline for decades (see Figure 1).

[2] One exception was on sorghum from the United States.

[3] In 2022, the spokesperson of the CCPIT was the Secretary-General of the CCOIC.

[4] Wary of the distortions caused from previous interventions in the corn market from 2015, China has since refrained from large-scale, direct interventions in feed grains.