1. Chinese language media in Australia

Two recently published papers shed some insights on Chinese-language media in Australia: Waning Sun’s journal article “Chinese-language digital news media in Australia” published in June in Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies and Fan Yang’s analysis “Translating tension” published last week by the Lowy Institute.

Sun focused her research on Sydney Today, while Yang looked at Daily Chinese Herald, Australian Chinese Daily and Media Today (parent company of Sydney Today) on two case studies: trade disputes, and Zhao Lijian’s “Afghan child” tweet.

Chinese-language media has come under the spotlight in recent years predominantly as a “national security concern”, particularly a “foreign interference concern”. The worry is that the Chinese Communist Party could use Chinese-language media to promote their foreign policy agenda. However, like on all issues, we must take a broader lens than just “national security” to really understand the scope and scale of the problem.

First, according to Sun’s research, “hard news” — that is, politics, economics, trade and foreign policy — represents a very small percentage of news covered by Sydney Today, in contrast to what most people may think what “news” should look like.

Instead, a typical popular news story is about cultural differences and often contains narratives such as “Chinese people behaving badly”, with quotes from English-language media serving as evidence of contempt from “mainstream society” of “Chinese people”. This then generates outrage and a sense of superiority from readers who are more “established” Chinese Australians, often siding with “mainstream society” and eager to delineate themselves from “new arrivals” or “Chinese people in China”.

Here we see it’s not a simple story of “us” vs “them” or China vs Australia. But it often devolves to “us” (established Chinese Australian migrants) trying to navigate between “mainstream society” and “Chinese people in China or new arrivals”.

Second, most of the stories are translations and compilations of stories from other sources rather than original stories. Sun found that compilations comprise 57 per cent of Sydney Today news stories whereas original items only comprise 5 per cent. And of the compilation items about Australia, 91 per cent came from English-language Australian media and government organisations. Yang found similar results, with only 2.2 per cent of the sample being original content.

This means the media organisations do not support journalists and reporters, but rely on curators 小编 who focus on selecting the topic and making the content appeal to the target audience — first-generation Chinese migrants. So the role played by these media organisations is very different. The line between “news” and “editorials” is also more blurred.

Readers of Neican probably are more interested in implications for politics and foreign policy. According to Yang:

Chinese-language media outlets in Australia are more likely to implicitly support Australian government policy than Chinese government policy when reporting on Australia–China tensions, despite published content often being moderated to remove direct criticism of China and the Chinese government.

And in a survey of 600 first-generation migrants from China, Sun found that “there is a high level of ambivalence about both Australia and China”.

So it appears that the scope and scale of CCP interference in Chinese-language media are rather limited. First, most news stories are not concerned about ‘hard news’ such as bilateral relationship, but rather cover topics that are pertinent to the first generation Chinese Australian community, such as crime. Of course, bilateral relationship is also a more sensitive topic, so their lack of coverage could be due both to market force and censorship pressure.

And for news articles on bilateral relationship, Chinese-language media in Australia overall did not “pick a side”. Yang found that “there is no single or consistent perspective being presented by these media outlets”. Sun also found that first-generation migrants from China do not unquestioningly accept the Chinese government narrative. This contrasts with the prevailing narrative that CCP has “infiltrated” Chinese-language media in Australia.

Censorship in media

Both Sun and Yang’s research points out that self-censorship is one of the pressures facing Chinese-language media in Australia, especially for media that publishes content on WeChat. These media organisations regularly soften or remove criticism of China and the Chinese government.

Although self-censorship pressures have not led to a uniform pro-Beijing editorial stance, national security analysts are right in pointing out that such self-censorship still poses a problem for freedom of speech in Australia.

Yet when faced with evidence of even more blatant incidents of censorship by a foreign government last week, Australia’s national security community is eerily silent about the foreign interference risks.

In Dateline Jerusalem: Journalism’s Toughest Assignment, John Lyons write:

This book is the story of why many editors and journalists in Australia are in fear of upsetting these people and therefore, in my view, self-censoring. It’s the story of how the Israeli-Palestinian issue is the single issue which the media will not cover with the rigour with which it covers every other issue. And, most importantly, it’s the story of how the Australian public is being short-changed — denied reliable, factual information about one of the most important conflicts of our time.

According to Jennine Khalik, a Palestinian Australian journalist, she was the subject of meetings between Israeli diplomats and editors at The Australian, and subsequently, she was moved to the Arts section so that she would not report on anything Palestine.

Now Chinese-language media affects around 4 per cent of Australians who speak a Chinese language at home. The scope of foreign interference detailed in Lyon’s book is far more significant, as it affects “mainstream media”, so that’s nearly every Australian.

Foreign interference and impediments to freedom of speech, including self-censorship, should be a problem no matter where the source of pressure is. Yet in the current public debate in Australia, “foreign interference” and “threat to freedom of speech” is usually only used when China is in the discussion.

This appears to be another instance where the government and national security community only pays attention to a problem when it has connections to China, rather than dealing with the issue more comprehensively.

2. US-China trade

It looks like trade policy under Biden is a continuation of Trump’s policy — it’s still very much “America first”. US Trade Representative Katherine Tai has pledged to keep pressuring Beijing to commit to the “Phase 1” trade deal, including the purchase agreement.

Tai said, “above all else, we must defend – to the hilt – our economic interests”.

As I’ve noted before, if China commits to the purchase agreement under the “Phase 1” trade deal, it will reduce China’s purchase of goods and services from other countries. This in effect means China must discriminate against other countries in favour of the US when importing. On this issue, the economic interest of the US is against the interest of many of its allies, despite Tai’s rhetoric of “collaboration with other economies and countries”.

As illustrated previously, China’s import of American agricultural products has already increased due to its sanction of Australian agricultural products, especially beef and lobsters. However, such an increase is still not enough to reach the “Phase 1” commitments.

On the other hand, the focus on China’s “non-market trade practices” would be more popular with other countries. Yet, as the US is criticising China’s industrial policies, the administration is also implementing its own industrial policies.

Overall, Tai’s speech indicates that the US is not pursuing general economic decoupling, as it is still trying to push for market access into China, which leads to more, not less, trade and economic linkages.

3. BRI debt

AidData, an international development research lab at William & Mary (a university in the US), has found a major increase in “hidden debt” in BRI projects, after analysing 13,427 Chinese development projects:

nearly 70% of China’s overseas lending is now directed to state-owned companies, state-owned banks, special purpose vehicles, joint ventures, and private sector institutions in recipient countries. These debts, for the most part, do not appear on their government balance sheets. However, most of them benefit from explicit or implicit forms of host government liability protection, which has blurred the distinction between private and public debt

This means previous official data on debt has undercounted debt obligations to China. And the “hidden debt” problem is getting worse.

The “hidden debt” problem is detrimental to global debt transparency. Opacity in debt creates unclear financial risks. Furthermore, it may affect global efforts on debt service suspension. China, a major world creditor, has not joined the Paris Club, a group of creditor countries that coordinates debt relief. It would not be fair for Paris Club members to provide debt relief only so that the debtor country can meet its obligation to China.

The report also reveals the extent that poorer countries have to rely on China for financing. China is outspending the US on a more than 2-to-1 basis. This means for countries that seek financing, there is little alternative available. It would be difficult for other countries to match China in the level of financing (for example under the Build Back Better World initiative).

Countries may be better off competing with China on quality rather than quantity, that is, with a focus on governance and standards. However, for countries desperate for financing, this is unlikely a priority.

4. Taiwan

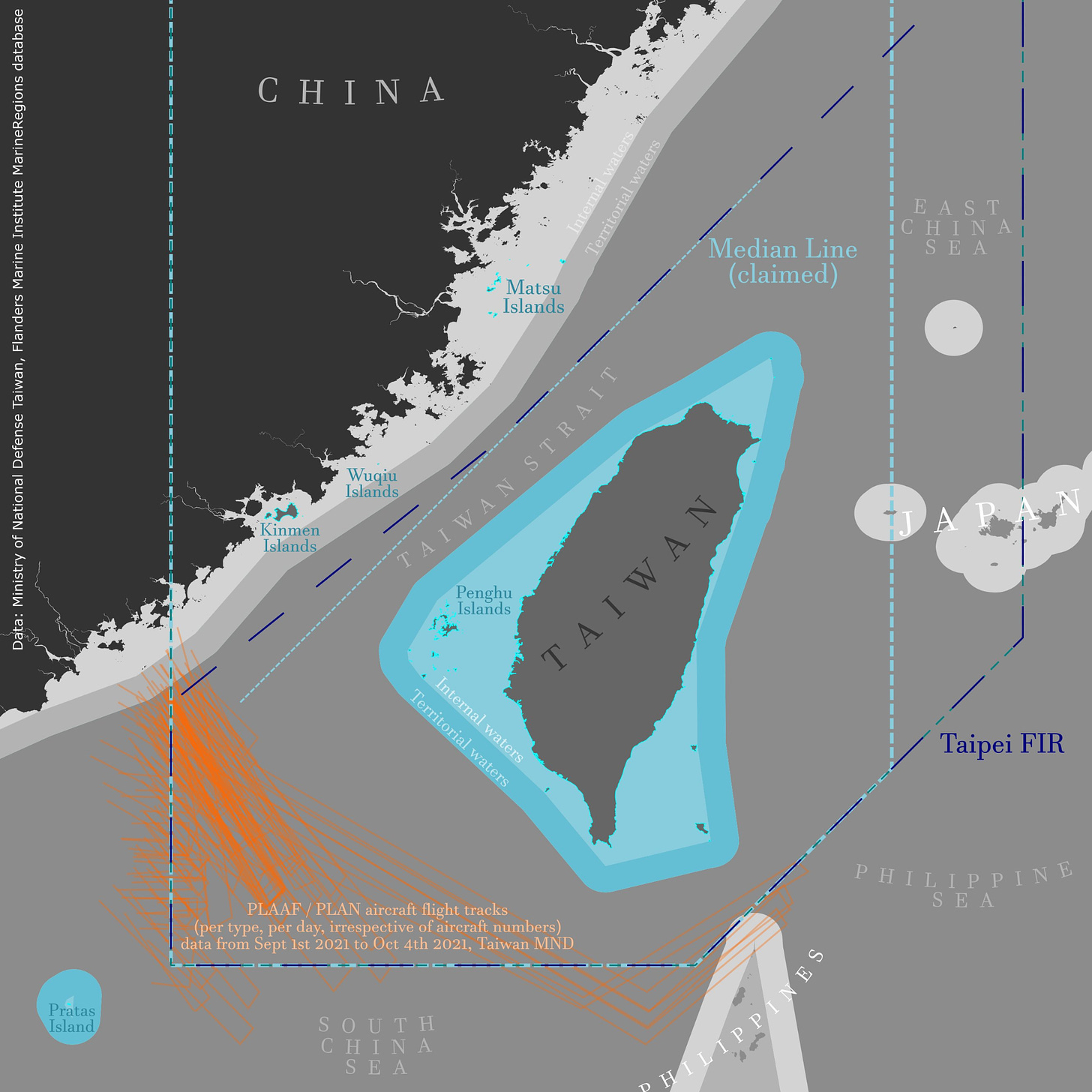

In recent weeks, China has been flying warplanes into Taiwan’s southwest “air defence identification zone”:

These flights are intended to provoke. But what is China trying to achieve through this provocative action? These flights move public sentiments within Taiwan even further away from China. Internationally, countries around the world are more sympathetic to Taiwan’s plight and see this as bullying by a great power. Within China, these flights are not being publicly promoted, so there is no benefit from the rise in nationalism.

According to Wen-Ti Sung, many Taiwanese do not see the flights as a preparation for invasion. He argues that these flights are part of a tactic to deter Taiwan from declaring independence:

One explanation is Beijing places a higher priority on deterring Taiwan’s further movement towards independence than promoting unification, so it is willing to trade the latter for the former. In other words, Beijing may simply not be as zealous about pursuing unification in the near-term.

Instead, keeping an eye on the long game, Beijing is willing to risk short- to medium-term costs in losing hearts and minds in Taiwan. The hope is, in time, it can eventually regain the initiative. For this reason, being able to deter further movement towards independence may be sufficient to buy China much-needed time.

This explanation postulates that China is continuing its past strategy of kicking the can down the road. As long as Taiwan doesn’t “declare independence”, China is prepared to wait. For this to work, both China and Taiwan need to believe that time is on their side. It is probably in the interest of the world that they both continue to wait for now.