Cities are sites of aspirations, illusions, and nightmares for Tibetans. During the COVID-19 epidemic, urban centres have become nightmarish spaces of fear and anxiety for many Tibetans. The city of Zö, on the northeast Tibetan Plateau, illustrates how lockdowns have affected Tibetans and how they have reacted to new government restrictions. Online information and control, as a relatively new means of governance, has played an important role in shaping and enforcing the norms of behaviour of residents of Tibetan cities in China.

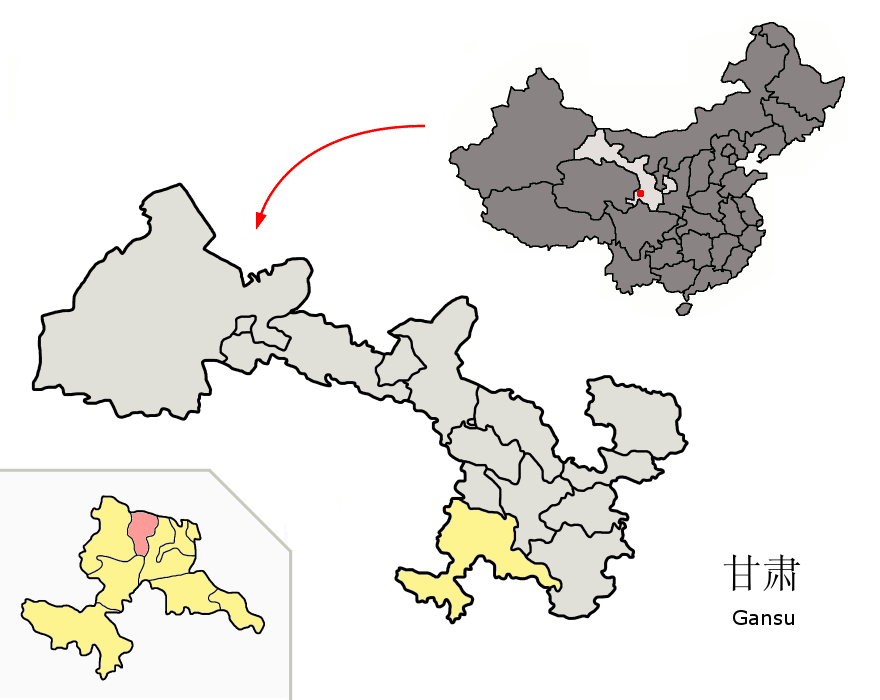

Zö (གཙོས་གྲོང་ཁྱེར; 合作市) is the capital of Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Gansu Province. The city is home to Tibetans, Han Chinese, and Muslim Hui, with Tibetans being the majority, constituting about 55 per cent of the city’s 87,000 residents.

As the coronavirus epidemic began unfolding in China in January 2020, eight cases were reported in Zö: the second highest number among Tibetan cities. The first patient was a Han Chinese migrant worker from Sichuan Province, who ran a mahjong house where he infected other mahjong players.

Croquant, Location of Hezuo within Gansu (China), CC BY 3.0

Croquant, Location of Hezuo within Gansu (China), CC BY 3.0

Transforming urban spaces

As soon as the first case in Zö was reported, the government enacted a strategy of “cooperative prevention and cooperative control” (联防联控), enabling relevant authorities, such as the police, traffic police and hospitals, to work together and share information about the spread of the virus, so that potential carriers could be tracked. In February, all exits and entrances to the city, along with its shops, restaurants and other public places, were closed. Residents were not allowed to leave their local community, and groceries were delivered by supermarkets and community workers after being purchased online.

The government tracked every person in the city who may have come into contact with the first patient. Some of them were taken directly to hospitals while others were told to self-quarantine at home.

During the epidemic, the streets of Zö became empty and quiet. Occasionally, police cars and ambulances appeared, while people retreated inside their homes. All public spaces temporarily became unavailable and all communication moved online. For many, urban space beyond the safety of home represented danger. The outside represented the state, while the inside represented society. Living in Zö at the time, I have never felt the power of the state so strongly.

Urban space moves online

As the number of cases increased, fear of infections intensified, and Tibetans encouraged each other to stay home. Meanwhile, the internet became an essential part of people’s lives. relying on social media apps such as TikTok and WeChat to bridge the gap between outside and inside, people seemed to be overwhelmed by information about the coronavirus. My friend Lhamo, for example, would check the coronavirus situation every morning when she woke up. She told me that otherwise she would have felt insecure and scared.

Meanwhile, Tibetans also shared information and connected with each other. Dondrub, another person I spoke to, said that he received lots of online information about the coronavirus from his friends and relatives every day, such as how to protect oneself from the virus. For him, this information was useful.

One of the most circulated videos during this period was by Zhong Nanshan, a leading epidemiologist in China. Many people trusted him and saw him as a hero because of his role in informing the public during the SARS outbreak, including by refuting efforts by the Chinese government to downplay the severity of the crisis. Acting according to his suggestions, people calmly locked themselves at home for a month, and believed their efforts would be successful in combating the outbreak. As Tsepal, another interviewee, related, he and his wife did what Zhong suggested,and cleaned and sterilised their toilet every time they used it to prevent virus transmission.

Monitoring online spaces

Social media in Zö – as elsewhere in China – is monitored by the government, and during the epidemic outbreak this was no exception. Even municipal governments opened official accounts on TikTok and WeChat, often announcing the latest development in the city.

“Rumors” about coronavirus and its social consequences were quickly addressed, and “rumor-makers” were punished. For example, Gonbu posted a message on a Wechat group about a Han Chinese man from Wuhan who had arrived in Zö city with fever and was quarantined. The local police determined that this is a “fake” message, and Gonbu was detained for ten days as a punishment. There was no space for what authorities deemed to be “rumors”. Thus, although Tibetans in Zö blamed Han Chinese people for bringing coronavirus to the city, barely anyone shared such information online because they were afraid that the authorities were closely monitoring online spaces.

During the epidemic, urban spaces in Zö were transformed as a result of government measures.In the process, online information came to play a vital role in governing the people and the city. In some ways,the virus has enabled the state to blur the division between online and urban spaces in the way it governs Tibetans.