The politics of time are an important dimension of Chinese state discourse about Tibet, yet one that has received relatively little attention to date. This piece examines the written and visual discourses about Tibet’s past, present and future across Chinese state media in the post-2008 era. The focus is on how these media discourses attempt to construct a very particular system of storytelling about the passage of time in Tibet in order to consolidate Chinese rule over the region. It also considers the ways in which new media practices have enabled the production and reproduction of Chinese state power over Tibet.

In January 2009, the People’s Congress of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) voted to establish Serf Emancipation Day as a new public holiday to commemorate the end of Tibet’s ‘feudal serfdom system’ and ‘the start of Tibetan democracy’. The new holiday would be observed on March 28th, also marking the 50th anniversary of China’s defeat of the Lhasa Uprising in 1959, which led to the dissolution of the Tibetan government and the Dalai Lama’s flight into exile.

Introduced just months after large-scale protests erupted across Tibet in 2008, the decision was criticised by activists and scholars as a distortion of history and a provocative move that could aggravate tensions at a time of already heightened Tibetan sensitivity.

Now more than a decade on, Serf Emancipation Day is ‘celebrated’ annually, and forms an important part of the Chinese state’s intensified efforts to reaffirm its territorial claims over Tibet through a tightened grip on the narration of the region’s past, present and future.

The Politics of Time in China and Tibet

Time is a deeply political affair, regularly used by those in power to construct a single, shared trajectory of linear progress. Such construction is done to consolidate order and control. Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, narratives of time have been an important tool for promoting national cohesion and historical consciousness. These two goals are underpinned by ideas of China’s linear progression from national humiliation to national salvation under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

The case of Tibet is perhaps the most prominent example of politics of time among territories currently claimed by the PRC. The public calls for independence, the Tibetan government in exile, and the international reputation of the Dalai Lama have variously challenged the Chinese state’s historical claims over Tibet as an inalienable part of China.

The state’s attempts to consolidate its own discourses about Tibetan temporality have increased since Spring 2008 when protests again erupted across Tibet. These protests were a response to frustrations, inequalities and broken promises arising from rapid economic development, as well as long-standing issues surrounding the legitimacy of Chinese rule in Tibet. They attracted considerable international attention, challenging once more official claims of ethnic unity and state legitimacy. They also led to an increasingly hard-line position from the Chinese state on Tibet’s historical status.

State media representations of Tibetan temporality

Media is a key site where ideas about time are produced and circulated to influence ‘temporal orientations’ towards present, past and future. Indeed, across Chinese state media, time is a central feature in both visual and written representations of Tibet.

Most state media reporting about Tibet make at least some passing reference to the changes that have taken place since the Lhasa Uprising in 1959. However, since 2008, considerably more attention has been given to contrasting ‘old Tibet’ (before 1959) and ‘new Tibet’ (after 1959). Such pieces emphasize oppression and suffering in ‘old Tibet’ to showcase what they claim was the cruelty of Tibet’s political and social order prior to ‘liberation’ in 1959. This can often be observed from their titles alone:

- Tibetan History: The Tragic Life of Tibetan People under Feudal Serfdom

- The Dark, Brutal Serfdom System of Old Tibet

- Valuable Historical Cases and Evidence: The Feudal Serfdom Was One of the Darkest Pages in the History of Humankind’s Development

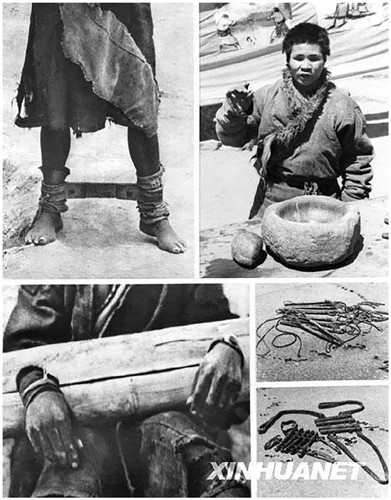

Stories of this kind provide detailed accounts of Tibetans ‘doing labour in shackles’, being ‘beaten to death’, and even being subject to torture practices such as ‘gouging out eyeballs, chopping off hands, cutting off feet, and skinning’. Photographs reinforce ‘old Tibet’ as a place of extreme brutality, with images of whips, chains and amputated limbs regularly used to further evidence abuse and suffering.

Images of implements used to torture Tibetan ‘serf’

Such representations of ‘old Tibet’ often appear alongside glowing depictions of ‘new Tibet’. While ‘old Tibet’ is described as a ‘hell on earth’, full of oppression, backwardness and darkness, ‘new Tibet’ is depicted as democratic, free and reaping the benefits of socialist transformation.

The most well-known example of this is ‘Contrasting New and Old Tibet’, a series of short videos produced by Tibet TV, the official television channel of the TAR between 2012 and 2017. Using the personal testimonies of older Tibetans, the videos begin by describing experiences of suffering in ‘old Tibet’, focusing on instances of hard labour and lack of food, before shifting to describing the progress and happiness experienced after ‘democratic reform’.

Images from a 2016 episode of ‘Contrasting New Tibet and Old Tibet’

Images from a 2017 episode of ‘Contrasting New and Old Tibet’

These discourses also look to the future. Tibet is often characterized as ‘thriving on a path of rapid modernization’ and striving towards ‘an even brighter future’. Tibet’s future and the CCP are closely bound together here. In one Xinhua piece in 2018, Mingji Cuomu, the vice president of Tibet Medical College, is quoted as saying,

Without the Chinese Communist Party, there could be no new Tibet. Only the Chinese Communist Party can save Tibet and develop Tibet.

State media is increasingly sophisticated and diverse in its discourses about Tibet, with new media technologies enabling new ways of visualising Tibetan temporalities. In 2019, to mark Serf Emancipation Day, People’s Daily released a series of music videos across their social media channels to the tune of ‘Me and My Motherland’, which featured several well-known Tibetan celebrities, ‘model workers’, students and others celebrating changes since 1959. They, along with other official media platforms, also livestreamed parades in Lhasa and Shigatse. The hashtag #2019西藏百万农奴解放纪念日# (2019 Anniversary of the Liberation of Tibet’s 1 Million Serfs) is used on WeChat and Weibo to increase the visibility of official celebrations. More recently, clips from documentaries such as ‘50 Years of Tibet’s Democratic Reforms’ (西藏民主改革50年) have also been embedded as GIFs in state media posts across social media.

Images from ‘Me and My Motherland’ music video

The online media also offer Tibetans a platform to form and disseminate counter discourses to audiences across China. However, despite the many creative tactics that Tibetans often use to challenge official discourses, they face constraints that diminish their online visibility.

Indeed, online spaces are a site of major power asymmetries. Competing with the state’s reach, online resources and its increasingly sophisticated tactics of digital persuasion is difficult. In addition, even greater challenges include heavy censorship and rising risks for challenging authority under Xi Jinping. It remains to be seen what these developments will mean for online spaces as a discursive battleground over the representation of Tibet’s past, present and future.