ON 13 JULY 2017, the 2010 Nobel Peace laureate Liu Xiaobo 刘晓波 passed away at the age of sixty-one. Tried and convicted in 2009 for ‘inciting subversion of state power’ for having co-authored Charter 08, a political manifesto calling for China’s democratic transformation, Liu is only the second Nobel Peace Prize laureate ever to die in custody (the first being Carl von Ossietzky, an anti-Nazi pacifist, in 1938).

His tragic fate — along with that of his wife Liu Xia 刘霞, who has spent years under house arrest despite never being charged with any crime — is a harsh reminder of Beijing’s stance on human rights. In the post-Mao age, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has consistently answered international criticism about its human rights abuses by insisting that the ‘universalist’ definition of human rights is a Western construct. In view of its own cultural tradition and developmental trajectory, the PRC has upheld the view that the realisation of economic and social rights, the right to development in particular, is of primary importance. In the official worldview of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), it is not a violation of human rights to deny basic civil and political liberties to its citizens, with freedom of expression being only one example. The Party-state measures human rights achievements in terms of the number of people who have been raised out of poverty,2 while detaining advocates for civil and political liberties, even those who protest against sexual harassment or speak out against corruption, despite corruption itself being a crime. Over the past several years, hundreds of rights activists have been detained in China. (See the China Story Yearbook 2015: Pollution, Chapter 2 ‘The Fog of Law’, pp.67–85, and the China Story Yearbook 2016: Control, Chapter 2 ‘Control by Law’, pp.43–57.) In September 2017, Kenneth Roth, the director of Human Rights Watch (HRW) went as far as to declare that ‘China’s [current] crackdown on human rights activists is the most severe since the Tiananmen Square democracy movement twenty-five years ago’.

The example of Liu Xiaobo also illustrates how, despite having an increasingly sophisticated legal system, the PRC, like other authoritarian regimes, is apt to use its laws and the loopholes therein to incriminate and eliminate political enemies. Criminal charges of ‘inciting subversion of state power’ and ‘subversion of state power’ are often invoked against individuals who allegedly challenge state security, social stability, and the political status quo. All the while, the PRC denies that it has political prisoners in its jails, insisting that people like Liu Xiaobo are just criminals. At the same time, his widow Liu Xia’s experience is testimony to the existence of a dual system, whereby the law applies in ‘ordinary’ cases but not in those circumstances that the authorities consider politically sensitive.

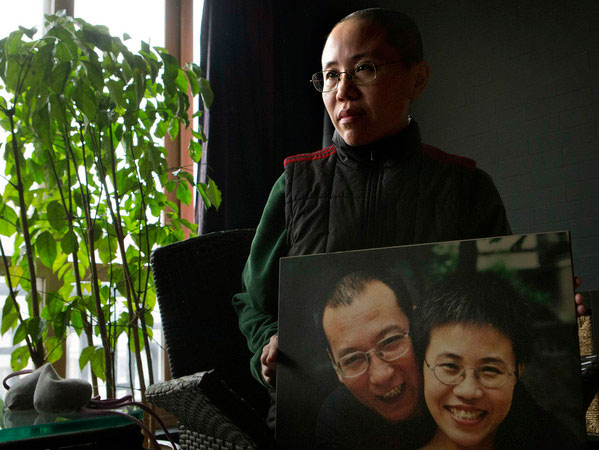

Liu Xiaobo’s ashes were scattered in the Yellow Sea (Liu Xia pictured centre, wearing sunglasses)

Source: YouTube

Liu Xiaobo’s death and the reaction to it by the international community testify to the increasingly prominent role that China plays in shaping human rights discourse within a divided international community. This essay analyses the mechanisms of the three main, and largely complementary, means through which the Chinese authorities attempt to rein in dissent within and outside of the law: judicial prosecution, torture, and harassment of relatives and friends.

Using the Law to Suppress Activism

As the latest annual report of the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC) noted, in 2017 the Chinese authorities ‘continued to use the law as an instrument of repression to expand control over Chinese society, while outwardly providing the veneer of a system guided by the rule of law.’ Chinese Party-state officials perceive human rights lawyers (weiquan 维权, or ‘rights defence’ lawyers) and civil society activists to be enemies of a stable and ‘harmonious’ society under the rule of law as defined by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). (See the China Story Yearbook 2015: Pollution, Chapter 2 ‘The Fog of Law’, pp.67–85.) Lawyers are considered particularly dangerous, because of their participation in the human rights discourse both at home and in international forums and media. Moreover, because of their plight, they often become international news themselves. Their pursuit of human rights claims at the grassroots leads them to become attached to ‘foreign’ ideas concerning human rights promoted by the Western organisations that support and cooperate with them.

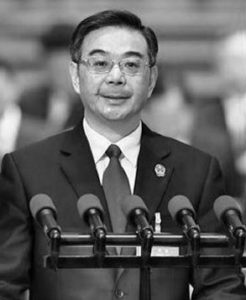

As in the past, human rights featured in the 2017 Supreme People’s Court’s (SPC) annual report, presented in March by Zhou Qiang 周强 — the current SPC President to the ‘Two Sessions’ (lianghui 两会) of the Chinese parliament, the National People’s Congress. Zhou’s report emphasised that the correct implementation of criminal justice policies protects human rights. But he also cited the sentencing ‘according to law’ of weiquan lawyer Zhou Shifeng 周世锋 to seven years’ imprisonment as one of the previous year’s key achievements in protecting state security.

Judicial authorities continue widely to use provisions in the 1997 Criminal Law concerning the crime of endangering state security 危害国家安全罪, (Articles 102–113) to bring human rights activists to trial and sentence them to lengthy imprisonment. The majority of human rights lawyers and activists detained in recent years were convicted under the terms of Article 105: ‘inciting subversion of state power’ 颠覆国家政权罪 or ‘subversion of state power’ 煽动颠覆国家政权罪.

Since the end of 2016, the list of rights activists under arrest has grown. Weiquan lawyers Jiang Tianyong 江天勇 and Li Heping 李和平, as well as activists Liu Shaoming 刘少明, Su Changlan 苏昌兰, and Chen Qitang 陈启堂, were all handed prison sentences for ‘subversion’ or ‘inciting subversion of state power’ in 2017. Their sentences ranged from three years to four and a half years, and most have been detained for at least seven months before trial. Lawyers Wang Quanzhang 王全章 and Wu Gan吴淦 were arrested and detained on similar charges, but they were tried in closed-door trials and their sentence remains unknown.

Another important case with significant international ramifications involved Taiwanese NGO volunteer Lee Ming-che 李明哲. In March 2017, the Chinese state security authorities detained him while he was travelling to Zhuhai via Macau. Ten days after his disappearance, the State Council Taiwan Affairs Office confirmed that he was under investigation for ‘endangering state security’. On 26 May, state security authorities in Hunan formally arrested him on suspicion of ‘subversion of state power’. Lee’s trial took place in September at the Yueyang Intermediate Court in Hunan. In a clip recorded at the trial, most probably filmed under duress, Mr Lee said that he had ‘no objection’ to the charges of ‘attacking Chinese society and encouraging multi-party rule’ and ‘inciting others to subvert state power’. They were similar to the charges against Liu Xiaobo. Filmed confessions have become increasingly common in ‘open trials’.

Torture

In 1988, the PRC ratified the International Convention against Torture. Over the following two decades, Chinese media and academic publications aired widespread condemnation of torture — a practice that the Chinese criminal legislation strictly prohibits under Articles 247–248 of the 1997 Criminal Law and Article 54 of the 2012 Criminal Procedure Law.

Under Xi Jinping, the Decisions of the Third and Fourth CCP Plenums in 2013 and 2014 also mention the strict prohibition of torture. Among the official affirmations of this principle are the 2013 Political-Legal Committee Provisions on Preventing Miscarriage of Justice 关于切实防止冤假错案的规定, which states that instances of torture and extracting confession through violent means or other acts of forgery should be severely punished — without specifying how — and that evidence obtained through torture or other illegal means is inadmissible in court. Similar points are made in the SPC’s Opinions on Preventing Miscarriages of Justice 关于建立健全防范刑事冤假错案工作机制的意见, of the same year. They both require judges to follow legal procedures strictly, and remind courts of appeal to countercheck judgements for which the evidence was sketchy or the facts unclear. The documents define illegally obtained evidence as confessions obtained outside a legal place of detention, and confessions that have no audio-video recording. There are problems in implementation, for example, ensuring proper audio-video recording of any interrogation and access to lawyers. But this reform is nevertheless impressive and builds on trials conducted in police stations and detention centres since 2006 (both documents are summarised in the China Story Yearbook 2014).

To add to this corpus of legislation, in October 2016, five central government bodies — the SPC, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of State Security, and the Ministry of Justice — issued a joint opinion that established the principle of putting the trial at the centre of criminal proceedings. The Opinion on the Promoting the Trial Centredness in Criminal Proceedings 关于推进以审判为中心的刑事诉讼制度改革的意见 obligates the procuratorate in certain important cases to directly question the criminal suspect about whether their confession had been coerced or if there had been illegal collection of evidence. In June 2017, the same bodies issued Regulations on Several Issues Concerning the Strict Exclusion of Illegal Evidence in Handling Criminal Cases 关于办理刑事案件严格排除非法证据若干问题的规定, which include provisions excluding evidence obtained by torture. During the ‘Two Sessions’ of March 2017, the Procurator-General, Cao Jianming 曹建民, reported that in 2016 the procuratorate corrected 34,230 cases of illegal investigation practices, including extracting confessions by torture. Still, as noted in the CECC 2017 Annual Report, there had been no instances of criminal prosecution of investigators who engaged in these abusive practices.

Notwithstanding increasingly sophisticated legislation on the subject, in 2017 torture still appears to be a widespread practice in both average criminal cases and cases involving human rights activists. The weiquan lawyers detained or harassed in the crackdown of July 2015, including Wang Quanzhang and Wu Gan as well as Xie Yang 谢阳, Wang Yu 王宇, and Li Chunfu 李春富, have revealed the ordeals and violence they were subjected to while in detention. According to a report compiled by the China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group, the Chinese authorities employed at least fifteen different types of torture or inhuman and degrading treatments against the lawyers and defenders held in the 2015 crackdown. These were intended to inflict physical harm and psychological detriment and included the use of electric shocks, sleep deprivation, and forced medications, among others.

In January 2017, to protest the decision of the authorities not to set him free after seventeen months of detention, Xie Yang’s legal team released the transcript of a conversation they had with their client. In it, Xie detailed the physical and mental torture to which he had been subject in detention. On 27 February, eleven diplomatic missions in Beijing wrote a letter to the Minister of Public Security, Guo Shenkun 郭聲琨, expressing their growing concern over claims of torture and other cruel or degrading treatments and punishments in cases involving detained rights lawyers and other activists.

In an unprecedented move, on 1 March, China’s official media responded to Xie’s allegations, and indirectly to the letter, claiming that he had fabricated the story about his torture to attract international attention. China’s state media accused lawyer Jiang Tianyong, who had been part of Xie’s legal team, of ‘making up fake news’; they featured an interview with him admitting fabricating Xie’s claims. In May, the Changsha Intermediate People’s Court released a video in which Xie admitted having being ‘brainwashed’ while overseas, attending training in Hong Kong and South Korea to ‘develop Western constitutionalism in China’. He also denied having been mistreated.

Stretching the Law Beyond its Limits

Violence, harassment, and intimidation of human rights activists or their families very often provide the corollary to legal measures. While arrests and detentions may expose the state to public scrutiny and have significant political costs, ‘measures operating in the shadows’ are sufficiently flexible to be used discretionarily by state authorities with fewer political costs. These include deprivation of physical liberty through ‘residential surveillance’ 监视居住 and ‘soft detention’ 软禁 (house arrest). Measures such as these are not strictly regulated by law. For instance, as mentioned above, Liu Xia has been under constant surveillance and intermittent house arrest since her husband’s arrest in 2008. After Liu Xiaobo’s death, she disappeared once again, and her friends were unable to contact her, despite official claims that she was ‘free’. She appeared in a YouTube video (in which the name of the filmmaker, as well as the place and date of filming were not specified) saying that she was mourning Liu Xiaobo’s passing outside Beijing; she apparently returned home only a month or so later.

The harassment of Liu Xia and her family and her years of constant surveillance and house arrest have occurred outside the remit of any established laws. And this is not unusual — many other activists’ partners and families are subjected to similar treatment.

Authorities reportedly harassed family members of those connected to the July 2015 crackdown through house arrest, constant surveillance, interference with their ability to travel, as well as pressuring landlords to evict them, and ordering school officials to deny admission to their children. This can go on for months or years. Families’ telephones are frequently tapped and their email traffic monitored. Police officers may watch and follow them, surveillance cameras may be installed near their homes and offices, and neighbours recruited to monitor them. Invitations to ‘have tea’ 喝茶 with state security agents (as discussed in the China Story Yearbook 2016: Control, Forum ‘Meet the State Security: Labour Activists and Their Controllers’, pp.65–73) or ‘being assigned a guard’ 被上岗 have been fairly common forms of intimidation for years. Authorities have closed organisations founded or operated by human rights defenders or strictly monitored their operations, rigorously controlling or cutting their sources of funding. Their offices and homes are recurrently subject to unauthorised searches, and they are frequently faced with heavy fines for trivial administrative transgressions.

One of the extra-legal measures used against lawyers since 2007 is the threat of disbarring them. The 2016 Amendment to the Measures on Managing Lawyers’ Practice of Law 律师执业管理办法 and Measures on Managing Law Firms 律师事务所管理办法 compel lawyers to support the Party’s leadership and prohibits them from provoking dissatisfaction with the Party and the government, signing joint petitions, or issuing open letters that ‘undermine the judicial system’, and organising sit-in protests or other kinds of demonstrations outside judicial or other government agencies. The Measures on Managing Law Firms require firms to establish internal Party groups that participate in policymaking and management. During a conference at the National Judges College in Beijing at the end of August 2017, Minister of Justice, Zhang Jun 张军, further called on lawyers to refrain from engaging in protests, criticising judges and courts, or speaking or acting for personal gain or to boost their reputation.

A Chilling Effect

Human rights lawyers and activists who have been harassed or ill-treated are warned or prevented from speaking out or writing about their ordeal. Yet over the past year, many victims of Chinese state repression have gone public. Labour activist Meng Han 猛汉, after spending twenty-one months in detention for ‘gathering crowds to disturb public order’, published online his ‘Notes from Prison’, which not only spoke about his experience, but also his reflections on and hopes for the future of the Chinese labour movement. He would have known that publishing this would bring him more trouble, and the police once again briefly detained him. But it did not deter him in the least. In a new development, spouses of imprisoned lawyers and activists have also begun speaking out.

As mentioned above, HRW has dubbed the recent crackdown against human rights defenders in China the worst since the suppression of the democracy movement in 1989. Even more worrying is the international accommodation of China’s actions. In September, HRW released a report that scrutinised China’s activities at the United Nations (UN). According to the report, on several occasions in 2017, UN agencies made concessions towards China on matters related to human rights. In January, UN officials kept an estimated three thousand staff and NGO representatives from attending a keynote speech by President Xi Jinping. In April, security officials removed ethnic Uyghur activist Dolkun Isa from the UN headquarters in New York, where he was attending a forum on indigenous issues. Isa is General Secretary of the World Uyghur Congress and now a German citizen, having sought asylum following persecution in China. In July, Isa was also stopped and briefly detained by the police in Rome, acting on a request from Chinese authorities who claim that he is a terrorist, although he has publically condemned all forms of terrorism.

These incidents raise serious questions about how the international community, including the UN, should respond to China’s human rights record at a time when China is exercising significant leverage on many countries in terms of economic statecraft, and has become the second-largest funder of the UN’s peacekeeping operations. While Chinese local activists continue to fight for rights under increasingly restrictive circumstances, they must surely be disheartened by this silence, if not complicity, by the international community. In July, while so many were grieving the death of Liu Xiaobo, US President Donald Trump was praising Xi Jinping as a ‘terrific’ and ‘talented’ leader. The roots of the ‘chilling effect’ might be closer to home than people in the Western world may think.

Notes

Ishaan Tharoor, ‘The Death of Liu Xiaobo Marks Dark Times for Dissent in China’, The Washington Post, 21 July 2017, online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/07/21/the-death-of-liu-xiaobo-marks-dark-times-for-dissent-in-china.

‘Big Strides Achieved by China in Human Rights Development’, Xinhua, 20 January 2017, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-01/20/c_135999905.htm

Congressional-Executive Commission on China, 2017 Annual Report, p.105, online at: https://www.cecc.gov/sites/chinacommission.house.gov/files/2017%20Annual%20Report.pdf.

‘Full Text of the 2017 Supreme’s People Court Work Report 最高人民法院工作报告2017年全文’, Haixia Dushibao, 13 March 2017, online at: http://www.mnw.cn/news/china/1625581.html.

Nectar Gan, ‘Isolated, Tortured, and Mentally Scarred… The Plight of China’s Persecuted Human Rights Lawyers’, South China Morning Post, 9 July 2017, online at: http://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/2101819/chinas-human-rights-lawyers-continue-fight-victims-709.

China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group, ‘Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatments in the 709 Crackdown: A Summary of Cases’, 9 July 2017, online at: http://www.chrlawyers.hk/sites/default/files/20170709%20-%20Torture%20in%20the%20709%20Crackdown%20%28ENG%29.pdf.

‘China Human Rights Lawyer Xie Yang “Admits Being Brainwashed” ’, BBC, 8 May 2017, online at: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-39843680.

Eva Pils, ‘ “Disappearing” China’s Human Rights Lawyers’, in Comparative Perspectives on Criminal Justice in China, Mike McConville and Eva Pils (eds.), Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2013, p.418.

The 1979 Criminal Procedures Law and its later revisions (1996, 2012) allow two distinct forms of residential surveillance, which differ depending on the location where the measure is carried out — either in or around the criminal suspect’s place of residence or, in exceptional circumstances, in a residence designated by the police (zhiding jusuo 指定居所). When there is ‘no fixed residence’ or ‘in cases involving offences of endangering state security, terrorism or extremely serious corruption’ (Article 73, 2012 Criminal Procedure Law), the law does not require for notification of the families about the detainees’ whereabouts or the charges they face. Over time, such exceptions have been used to widen the scope of ‘residential surveillance’, which has merged with other extra-legal measures including enforced disappearance or incommunicado detention.

‘Chinese Nobel Laureate’s Widow Makes First Appearance since Funeral’, Reuters, 19 August 2017, online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-rights/chinese-nobel-laureates-widow-makes-first-appearance-since-funeral-idUSKCN1AZ02O

See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=glvpLRL-bT4

Yaxue Cao, ‘Drinking Tea with the State Security Police — Who Is Being Questioned?’, Seeing Red in China, comment posted on 11 March 2012, online at: http://seeingredinchina.com/2012/03/01/drinking-tea-with-the-state-security-police-who-is-being-questioned/

Human Rights Watch, Walking on Thin Ice: Control, Intimidation and Harassment of Lawyers in China, 2008, online at: https://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/china0408/china0408web.pdf.

Meng Han, ‘Notes from Prison (Part 1 and 2)’, China Change, 10 October 2017, online at: https://chinachange.org/2017/10/10/notes-from-prison-part-one-of-two; and https://chinachange.org/2017/10/11/notes-from-prison-part-two-of-two/

Human Rights Watch, ‘World Report 2017: China’, 2017, online at: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2017/country-chapters/china-and-tibet.

Human Rights Watch, ‘The Costs of International Advocacy: China’s Interference in United Nations’ Human Rights Mechanisms’, 5 September 2017, online at https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/09/05/costs-international-advocacy/chinas-interference-united-nations-human-rights.