An Uncertain Year of the Goat

On 15 February 2015, four days before the start of the Lunar New Year, Xi Jinping met with local residents in the Yanta district 雁塔区 of Xi’an. He admired the Spring Festival papercuts they had made and selected one with a traditional ‘three goats’ 三羊 design. Photographs of Xi holding the papercut in both hands, and other photographs of him chatting or shaking hands with different groups of people in Xi’an, soon appeared in print and online. Xi has often called Xi’an, the site of China’s famous ancient capital Chang’an, his hometown—he was born in Fuping county 富平县, only an hour’s drive away. These images, which projected an aura of harmonious cordiality between a beaming General Secretary of China’s Communist Party and people who appeared visibly excited to be in close physical proximity to him, marked an auspicious start to the Year of the Goat for China’s one-party state.

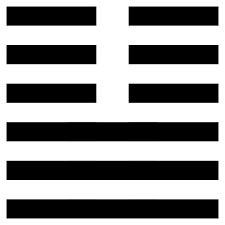

As the first day of the Year of the Goat approached in 2015, Chinese cities and towns were awash with advertisements, festive banners, and papercuts featuring ‘three-goat’ designs. Luxury Swiss watch companies keen to capitalise on the appetite for goat symbolism among wealthy Chinese customers produced limited edition watches featuring single and triple goat designs. ‘Three goats’ is a visual pun for hexagram eleven in the early Chinese classic, the Book of Changes. The hexagram, which symbolises ‘grandeur’ 泰, consists at its base of ‘three yang lines’ 三阳 (that is, unbroken lines). The hexagram’s top three lines are yin (broken) lines. This symmetrical arrangement of three yang lines and three yin lines is regarded as highly auspicious. For divinatory purposes, the hexagram augurs greatness: ‘the three yang lines pave the way to grandeur’ 三阳开泰. This saying has long served as a New Year greeting and is especially popular during goat years because ‘three goats’ and ‘three yang lines’ are both pronounced san yang in Chinese. Hence the saying is also often written as: ‘May the three goats bring grandeur your way’ 三羊开泰.

However, the festive euphoria of the week-long Spring Festival celebrations (18–24 February) was overshadowed by ongoing, widespread anxieties about pollution and financial volatility. The 2015 Yearbook is titled Pollution but environment and economy are interlinked in complex ways that preoccupied both Party and people throughout 2015.

Goat symbolism: Jaquet Droz Ateliers d’Art watches celebrating the Year of the Goat

Source: timetransformed.com

The state-imposed presence of a ‘collective vision’ has enabled us to organise each of our Yearbooks around a theme that illuminates a key feature of life and society in the People’s Republic during that year. For 2012, it was the rise of China’s ‘red boomers’ (or ‘revolutionary successors’, the ‘princeling’ children of the first generation of Chinese Communist leaders). Xi Jinping and Bo Xilai had emerged in the late 2000s as the two most prominent of these ‘red boomers’. That year saw the political demise of Bo and the rise of Xi to the leadership of both Party and state as chairman of the Chinese Communist Party and President of the People’s Republic of China. In 2013, we considered the prominence accorded to ‘civilisation’ in China’s official and public culture and discourse that year, with state-led ‘civilising’ projects in fields as varied as economics, education, politics, and social and urban planning. In 2014, Xi Jinping’s vision of China as leading a regional ‘community of shared destiny’ led us to explore how, as the world became increasingly dependent on China’s economic prosperity, the Chinese government and Chinese citizens were also finding a place for themselves in the world.

As with the themes of previous years, we have chosen a Chinese character, 染 ran, to express the idea of the 2015’s theme of pollution. The basic meaning of the verb 染 is ‘to dye’ and it appears in the range of compound words that are used to describe different forms of dyeing, including the ‘dyeing’ (painting) of fingernails and toenails 染指甲 ran zhi jia.

By extension, 染 has also come to mean pollution in the sense of an agent or force that produces a negative change in an object, person or substance. Accordingly, 染 is part of the Chinese word for pollution 污染 wuran. The word meant ‘contamination’ or ‘defilement’ in its premodern usage, of which a well-known instance appears in a statement attributed to the seer Guan Lu 管辂 (209–256) in the third century work, Records of the Three Kingdoms 三国志: ‘The bleeding bodies of dead soldiers defile the hills and mountains’ 军尸流血,污染丘山. As a modern word wuran refers mainly to environmental pollution and appears in terms denoting particular types of pollution, such as air pollution 空气污染 or the pollution of drinking water 饮水污染. Other negative connotations of the verb 染 include the Buddhist-derived expression ‘to acquire a bad habit’ 染恶习 ran e’xi; the term for ‘contracting an infectious disease’ 染病 ranbing, and the compound verb 染指 ranzhi, which refers to inappropriate uses of power and overreaching influence (whether of a country, group or individual). For instance, in January 2015, China’s state media used the phrase ‘encroachments on cultural circles’ 染指文化圈 to publicise the launch of the state’s investigations into how corrupt officials were manipulating the workings of China’s elite art market. These varied senses of 染 capture something of the complex trajectories of pollution as a Chinese idea.

Also, as in previous years, the organisation of the chapters, forums, and information windows reflects the research themes of the Australian Centre on China in the World, including justice, numbers, text, time, urban, and everyday life, with specific focuses on culture and foreign relations (with special attention to China’s relations with Australia). We explore the relation between pollution and money through such questions as: Why have so many Chinese farmers chosen to gamble on the stock market instead of investing in farm equipment? Why, despite predictable environmental consequences, has Xi Jinping’s administration pushed so hard for the restructuring of the city of Beijing and the creation of the massive city-region called Jing-Jin-Ji (encompassing Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei)? Why have the party-state’s commitments to resolve environmental problems in China, including the considerable suite of environmental laws it has already enacted, achieved very little to date? It is not only China that is ‘under the dome’ of its pollution (to borrow the title of a popular—and then suppressed—2015 documentary on pollution that is also the title of the opening chapter by Jane Golley). The country’s ambitious plans for a ‘new silk road’ over land and sea in particular illustrate how we all share the same sky.

We also reflect on the further extension in 2015 of the party’s ‘mass education’ campaign that was first launched in 2013. Xi’s administration has shown a particular determination to ‘reform’ Chinese minds. As China’s ‘opening up’ and integration with the global economy proceeds apace, the Party appears all the more intent on prescribing what citizens can and cannot do, write and even think. Accordingly, ‘Reform and Opening Up’ has acquired a highly particular connotation at odds with its original meaning. As the post-Maoist party-state’s guiding motto throughout the 1980s (it was first introduced in December 1978), the slogan signalled a commitment to gradual political liberalisation (though never full democratisation) to complement the economic reforms already underway.

Throughout 2015, the government led by Xi has sought to more effectively align the thinking of its citizens with that of the Party through new restrictions on the nation’s educational curriculum (particularly at university level), tightened censorship, and an unprecedented crackdown on rights and civil society activism that resulted in the arrest of more than one hundred ‘rights-defence’ 维权 lawyers and activists in July 2015. The current Party leadership’s understanding of political ‘reform’ is nowhere more evident than in its interpretation of the rule of law as a governing tool aimed at the preservation of the Party’s authority.

The year also saw the continued prosecution of corrupt party and state officials: a key event being the closed-door trial in June 2015 of Zhou Yongkang, former head of China’s all-powerful state security. In 2015, the Party-state also introduced tougher penalties for environmental pollution, pressed on with massive building and infrastructure construction as part of the urbanisation drive, built more artificial islands in the South China Sea, and drew up an action plan for China’s global economic role, based on the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and ‘Twenty-First Century Maritime Silk Road’ initiatives first proposed by Xi in late 2013. In their public statements on these matters, party leaders and official spokespersons resolutely presented a grand narrative about China’s present and future.

However, events that challenged that narrative appeared to have taken them by surprise, eliciting less certain, even erratic behaviour. For instance, officials praised Chai Jing’s 柴静 phenomenally successful documentary on air pollution and environmental degradation Under the Dome 穹顶之下 when it was released online on 28 February 2015 but shut it down three days later—after it had been viewed almost 200 million times. From June 2015, as prices tumbled on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges, the government moved rapidly from trying to prop up share prices with public funds to introducing incentives to boost investor confidence, to introducing penalties for short selling and finally demanding that China’s top brokerages invest funds to stabilise the stock market. Disjunctures between planning and reality are a problem for governments everywhere. In China, the opaque nature of the one-party system complicates the picture. But this authoritarian system also means the state is involved in everyone’s life—and various Internet forums readily expose the gaps and contradictions between the party’s narrative of a ‘collective vision’ and the diverse stories of average citizens. These gaps and contradictions have served as a framing device for the China Story Yearbook project since its launch in 2012.

On Pollution

Pollution is both an omnipresent physical hazard for people living in mainland China and a powerful metaphor for the things the current regime sees as a threat to its ability to maintain power and the People’s Republic itself. Xi’s administration seeks to eradicate not only the pollution of the natural elements (air, water, soil), but also ‘polluting’ ideas and those whom they have identified as agents of these polluting ideas (whether individuals, groups, or organisations).

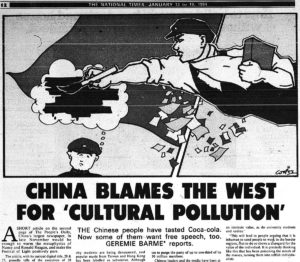

Back in 1983, when he was trying to work out how to reform the economy while keeping control over society, ideas, and politics, Deng Xiaoping launched an ‘anti-spiritual pollution’ 反对精神污染 campaign to silence critics, clamp down on newly emerging social freedoms and cleanse the cultural scene of such pollutants as abstract art, pop music, and ‘misty’ poetry 朦胧诗. The Party’s fear of spiritual pollution never quite went away, but it has intensified under Xi Jinping since 2013. In May 2015, at the height of the party-state’s crackdown on dissenting voices in media, law, and academe, Xi Jinping stated: ‘Political and natural ecology are the same—neglect them even a little and they will very quickly become contaminated’.

Futu, Hebei: ‘Practice the Thought of Three Represents, advance the reform on rural tax system’

Source: en.wikipedia.org

Xi’s rhetoric marks a decisive shift away from the approaches adopted by the previous administrations under Jiang Zemin (1989–2002) and Hu Jintao (2002–2012). Towards the end of his tenure in 2001, as socioeconomic inequalities deepened in China, Jiang introduced the concept of the ‘Three Represents’ 三个代表 to affirm the role of wealthy businesspeople in the nation’s economic development and to consolidate the links between the one-party system and private enterprise. As Jiang’s successor, Hu continued to strengthen this relationship while promoting a ‘harmonious society’ as a way of managing the growing gulf between haves and have-nots. Both Jiang and Hu relied on the collective style of management that Deng established at the Party’s historic Third Plenum in 1978 and that formally ended the Maoist era.

Xi, conversely, has demanded that even the upper echelons of the Party submit to his leadership as he focused on eradicating corruption in the party’s ranks, a task which the two previous administrations also prosecuted but with much less success. In this process, Xi, departed significantly from the collective work style of his two immediate predecessors. Throughout 2015, party publications and state media energetically promoted Xi’s image as a strong, enlightened, and morally superior leader. He has spoken of forging cadres (especially high-level cadres) with ‘four iron’ qualities ‘四铁’干部: an ‘iron-like’ belief and faith in the Party and an iron-clad discipline and sense of responsibility.

Under Xi, the Chinese government views the country’s environmental problems and ideological consolidation as inextricably linked. They perceive cleaning the nation’s air, safeguarding its land, and purifying the water of its rivers, lakes, and coast as requiring not only scientific, technological and policy solutions but ideological commitment and a dedicated cadre of party and government officials as well.

This China Story Yearbook 2015 tracks three narratives of pollution:

Environmental Pollution

Land-grabbing urbanisation and soil and water contamination is increasingly placing agriculture in China under stress. Several of our stories describe how both governments (central and local) and citizens have dealt with and responded to the challenges of pollution and contamination. We also look at how pollution has come to play a defining role in urban design and mega-city planning in the north and the repercussions of pollution on China’s growth.

We also consider the complexities of implementing expensive and massive engineering solutions to address water scarcity and pollution and how cities struggle to provide a livable environment for an urban population destined to grow dramatically over the next decade. We note how a massive, catastrophic chemical explosion in an urban industrial warehouse in Tianjin in August 2015 exposed shortcomings in areas ranging from regulation to security and safety and emergency response preparedness that were the results of rapid and poorly planned industrialisation and how this incident exacerbated anxiety around the subject of pollution in both the populace and the leadership.

24 November 2015: Liu Shenkui writes an opinion piece on the ‘pollution’ of ‘Taiwanese independence’

Source: fjrb.fjsen.com

Ideological Pollution

The Chinese government’s intensification of censorship and propaganda is an important part of the 2015 China story. We provide accounts of how it has sought to banish ‘Western values’ (meaning, broadly, ideas of a liberal democratic persuasion) from university classrooms, and how, in linking ‘de-Westernisation’ to a strengthening of ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’, it has further politicised China’s legal system in the name of reform.

In 2015, while tightening existing restrictions on free discussion, the party-state gave free reign to online abuse against the idea and promoters of Taiwanese independence. In the months leading up to the Taiwanese general election of 16 January 2016, and as the party leadership redoubled its efforts to strengthen diplomatic and trade ties with Taiwan, nationalistic Chinese netizens denounced Taiwanese independence. Some even called it a ‘polluting’ idea. For instance, an opinion piece of 24 November 2015 in the Fujian Daily included this line: ‘Waste pollution and air pollution makes us angry but the “pollution” of “Taiwanese independence” is much more hateful’. When Tsai Ing-wen of the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party was elected as Taiwan’s first female president, media commentators speculated that Taiwanese resentment at abusive online mainland discourse had played a part in the DPP’s landslide victory.

Agents of Pollution

If things and ideas can be polluted, so can people. In June 2015, the trial of Zhou Yongkang was reported in ways that signaled the Party leadership’s determination to root out the ‘contagion’ of corruption, even if it meant taking down people in high positions. Zhou’s family members and many other senior Party and state officials linked to him have since gone down as well, and almost every province has experienced the fall of at least one important leader.

Under Xi, the government has targeted many ‘unhealthy’ practices. This year saw the introduction of strict new regulations to ban smokers from public places and the imposition of heavy fines for disobedience. However, people who mounted their own campaigns risked being viewed as pollutants themselves. When the ‘Feminist Five’ sought to raise awareness of sexual harassment on public transportation in March 2015, they were arrested, and other activists defending, for example, the rights of minorities, were also detained. To prevent the contagion effects of social activism, public security authorities throughout 2015 frequently charged people with the crime of ‘picking quarrels and provoking trouble’.

Predictions and Reckonings

When a newly-appointed Xi Jinping announced in November 2012 that achieving the ‘Chinese Dream’ 中国梦 would be his primary goal, people had little idea of how far he would go to protect his vision from perceived contaminants and threats. In 2015 and early 2016, an energetic debate has taken place outside China on the question of whether he—and China’s Communist party-state—would succeed or, ultimately, collapse.

The dissident blogger Mo Zhixu 莫之许 (pen name of Zhao Hui 赵晖) wrote in April 2016 on Chinaorg.com that the previous year had seen a shift in the views of ‘mainstream Western scholars’ about ‘the future prospects for Chinese Communist rule’. They had previously argued, he observed, that China’s authoritarian regime would remain ‘resilient’, a thesis first elaborated by Columbia University-based political scientist Andrew Nathan in 2003. But now they were seemingly defending the opposite view. The ‘resilience and adaptation’ argument perceived the regime as uniquely capable of adapting to changing conditions and using its institutions to manage conflicts and transitions. In 2015, David Shambaugh, an influential American analyst of Chinese affairs and professor of politics at George Washington University, a previous supporter of the ‘resilience and adaptation’ argument, published a book, China’s Future, that featured a big question mark on its cover. Shambaugh was now predicting the progressive and ultimately fatal decline of China’s one-party system, as were commentators like Pei Minxin 裴敏欣, professor of government at Claremont McKenna College, who had long warned that Chinese communism was ‘trapped’ in ‘transition’. Pei more recently began speaking in terms of Chinese communism’s imminent ‘twilight’.

Whether or not one subscribes to the particular views held by Mo, Shambaugh, and others, it is undeniable that academic and online commentary about China’s ‘unstable and unsettled’ future is on the rise, including, to the extent allowed by China’s rigorous system of censorship, within China itself. Certainly, China suffers from rampant corruption, the flight of domestic capital, an ideology that struggles for true believers among China’s citizens, increasing repression of dissent (real or imagined) by an increasingly insecure regime and an economy with deep structural weaknesses. However, none of these phenomena are new, and they haven’t taken China to the brink yet. In his review of Shambaugh’s China’s Future, historian Jeffrey Wasserstrom of the University of California Irvine agreed with much of Shambaugh’s analysis, but did not ‘buy [Shambaugh’s] notion that the past performance of developing countries provides a clear guide for China’s future’. Will 2015 herald the collapse of one-party rule in China or will it be merely the prelude to the one-party system’s solidification under Xi Jinping’s strongman tactics? The outcome will not depend on Xi’s decisions alone.

Geremie Barmé, founding director of the Australian Centre on China in the World, used the term ‘collapsism’ to describe the raft of pessimistic predictions among those who professionally comment on Chinese affairs. In a March 2015 interview, he noted that such speculation among American commentators in particular may have more to do with ‘huge anxiety about US politics and its future’ than with China per se. Barmé remarked: ‘Xi’s China is uglier, more repressive, and narrow, yet it’s more confident, more articulate and more focused than at any time since Mao Zedong. That’s why America is worried’.

Throughout 2015, many mainland public intellectuals have expressed dismay at the increasingly authoritarian nature of China’s political culture. The dismay spread beyond China’s borders when, between October and December 2015, Chinese state agents carried out cross-border abductions of three Hong Kong booksellers from Causeway Bay Books while detaining two more of the bookshop’s staff when they visited family in Guangdong province. The bookshop, with its reputation for publishing works critical of China’s Communist Party leadership and selling titles banned on the Mainland, had long been a thorn in the side of the Chinese government. The governments of Western democratic countries denounced these extra-territorial abductions, with senior government figures in the UK and Sweden pressing for the release of two of the detained booksellers who held, respectively, British and Swedish citizenship (see Information Window ‘The Causeway Bay Books Incident’, p.xxiii).

In 2015, the Chinese government also continued to request assistance from other countries to repatriate corrupt Chinese officials who had fled overseas. At the same time, it established a new Department of Overseas Fugitive Affairs to pursue economic fugitives abroad. This posed new and difficult problems for the governments of Western democracies, apprehensive about returning people to face a highly politicised justice system. The term 染指 (mentioned earlier) allows us to say that, given the substantial amount of money that corrupt Chinese officials have transferred abroad, Western democracies must now contend with the ‘encroaching’ effects of those ill-gotten gains as well as Xi’s anti-graft campaign. The intricate networks of financial and political power that have enabled the families of senior party leaders, including Xi Jinping, to amass vast and unaccountable fortunes, are now a global problem. As Chinese investments in commercial, industrial, and property developments outside China continue to grow, countries such as Australia whose economies have become heavily dependent on trade with and investment from China, are increasingly forced to reckon with the country’s political complexities.

There is clear popular support in China for Xi’s anti-graft campaign but the relationship between the Party and the people is a delicate balancing act. With unilateral decision-making comes enormous, almost paternal responsibility. The Party expects the people to obey its directives. In return, the people expect the Party to ‘serve the people’—to ensure their socioeconomic and environmental well-being, and in more far-reaching ways than is expected of governments in democratic societies. Whether the Party-state is able and willing to meet these needs and expectations is one factor, but a big one, in determining its future and that of China itself.

The China Story Yearbook

The China Story Yearbook is a project of the Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW) at The Australian National University (ANU). It is part of a broad undertaking aimed at understanding what we call the China Story 中国的故事, both as portrayed by official China, and from various other perspectives. Our Centre on China in the World is a Commonwealth Government-ANU initiative that was announced by then Australian prime minister, the Hon Kevin Rudd MP, in April 2010 on the occasion of the Seventieth George E. Morrison Lecture at ANU. Geremie Barmé was its director from its founding through to 2015.

The Centre is dedicated to a holistic approach to the study of contemporary China: one that considers the range of forces, personalities, and ideas at work in China as a means of understanding the spectrum of China’s sociopolitical and cultural realities. The Australian Centre on China in the World fosters such an approach by supporting humanities-led research that engages actively with the social sciences. The resulting admixture has, we believe, academic merit, public policy relevance, and value for the engaged public. The Yearbook is aimed at a broad readership that includes the general public as well as scholars from all fields, as well as people in business and government.

The Australian Centre on China in the World promotes the New Sinology of which Geremie Barmé was a pioneer (https://www.thechinastory.org/new-sinology/). This is a study of China underpinned by an understanding of the disparate living traditions of Chinese thought, language, and culture. Xi Jinping’s China is a gift to the New Sinologist, for the world of the Chairman of Everything requires the student of contemporary China to be familiar with basic classical Chinese thought, history and literature, appreciate the abiding influence of Marxist-Leninist ideas, and the dialectic prestidigitations of Mao Zedong Thought. Those who pursue narrow disciplinary approaches to China today serve well the metrics-obsessed international academy. However, they may be incapable of understanding and explaining the historically-derived and culturally-fostered ideas and practices that shape both government and society in mainland China.

Most of the scholars and writers whose work features in the China Story Yearbook 2015: Pollution are members of, or associated with the Australian Centre on China in the World. They survey the China of Xi’s third year as leader of the Party and state through chapters, forums, and information windows on topics ranging from economics, politics, and China’s regional posture through urban change, social activism and law, the Internet, cultural mores, and present-day Chinese attitudes to history and thought. Their contributions, which cover the twelve-month period in 2015 with some reference to events in early 2016, offer an informed perspective on recent developments in China and what these may mean for the future.

The Five Elements (from top, counterclockwise); fire, metal, water, wood, and (in the middle) earth

Source: zh.wikipedia.org

The Yearbook is organised in the form of thematically arranged chapters which are interspersed with information windows that highlight particular words, issues, ideas, statistics, people, and events. Forums, or ‘interstices’, expand on the contents of chapters or discuss a topic of relevance to the year. This year, we have signposted the Chapters using the Five Elements 五行 of early Chinese thought—water, fire, wood, metal, and earth. The five elements were used for reckoning time and remain widely used to this day for Chinese astrological calculations. The traditional Chinese belief that all phenomena of the known world are the result of dynamic interactions among these five elements offers a useful analogy for the intricately interdependent nature of events and trends in a globalised China. As 2015 was the Year of the Wood Goat, we have highlighted the wood element by featuring it twice.

A Chronology at the end of the volume provides an overview of the year under discussion. Footnotes and the CIW-Danwei Archive of source materials are available online at: https://www.thechinastory.org/dossier/.

Acknowledgements

The 2015 Yearbook represents the collective effort of all of its contributors, of whom Gloria Davies, Jeremy Goldkorn, Jane Golley, Linda Jaivin, and Luigi Tomba also played an editorial role. We take this opportunity to acknowledge the enormous contributions made by the CIW’s Founding Director, Geremie R. Barmé, in creating and leading the China Story Yearbook project from 2012 to 2015. Barmé steered our discussions of this Yearbook and up to his retirement from the Australian National University in November 2015, when the planning of this Yearbook was underway. We would also like to thank Jeremy’s colleagues at Danwei Media in Beijing—Jip Bouman, Emily Feng, Lorand Laskai, Oma Lee, Lucille Liu, Siodhbhra Parkin, Matt Schrader, Nick Stember, Xiaonan Wang, and Aiden Xia—who provided updates of Chinese- and English-language material relevant to the project and helped to compile and write some of the information windows in the chapters and forums. We are deeply grateful to Linda Jaivin for her extensive and painstaking editorial work on various drafts of the manuscript, to Lindy Allen for typesetting, and to Sharon Strange for typesetting, providing excellent editorial advice and assistance, as well as keeping everyone on track.

Cover of the China Story Yearbook 2015, showing the Chinese character 染, which is embossed on swirls of Chinese black ink

Artwork: CRE8IVE, Canberra

The Cover Image

The Yearbook cover features the Chinese character 染 ran, ‘to dye’, embossed on swirls of Chinese black ink. 染 forms part of the Chinese word for pollution 污染 wuran, the theme of this year’s Yearbook. Among the metaphorical and literal connotations of pollution expressed in this Yearbook through 染 are to adulterate, contaminate, spoil or violate.

Notes

‘Xi Jinping holds a Spring Festival papercut and offers New Year greetings to the people of China’ 习近平手持“三阳开泰”剪纸向全国人民拜年, people.cn, 16 February 2015, online at: http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2015/0216/c1024-26573390.html

Ambrose Lancaster, ‘Watches for the Year of the Goat’, 26 February 2015, online at: http://timetransformed.com/2015/02/26/watches-for-the-year-of-the-goat/

A state media article draws attention to the image of Xi Jinping holding the ‘three-goat’ papercut and explains its symbolism. ‘What’s the meaning of san yang kai tai?’ “三阳开泰”到底什么意思?, people.cn, 19 February 2016, online at: http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2015/0219/c1001-26584006.html

Yang Fan 杨帆, ‘Are seventeen years of repeated prohibitions sufficient to deter encroachments on cultural circles by officials?’ 17年禁令重重,难挡官员染指文化圈?, people.cn, 21 January 2015, online at: http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2015/0121/c1001-26421731.html

Fan Xutao 潘旭涛, ‘Flush out the filth and make things clean to win the hearts of the people: Xi Jinping’s keywords on government, no.31, political ecology’ 激浊扬清 凝聚民心; 习近平治国理政关键词 (31)政治生态, people.cn, 16 May 2016, online at: http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrbhwb/html/2016-05/16/content_1679279.htm

The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, ‘Dictionary of Xi Jinping’s New Terms’, 30 December 2015, online at: http://www.scio.gov.cn/32618/Document/1460610/1460610.htm

Anne Henochowicz, ‘Minitrue: Trolling Tsai Ing-wen Beyond the Great Firewall’, China Digital Times, 22 January 2016, online at: http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2016/01/minitrue-trolling-tsai-ing-wen-beyond-great-firewall/; Chris Buckley and Austin Ramzy, ‘Singer’s Apology for Waving Taiwan Flag Stirs Backlash of its Own, The New York Times, 17 January 2016, online at: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/17/world/asia/taiwan-china-singer-chou-tzu-yu.html

Mo Zhixu, ‘China’s Future: Unstable and Unsettled’, Chinachange.org, 16 April 2016, online at: https://chinachange.org/2016/04/06/chinas-future-unstable-and-unsettled/

David Shambaugh, China’s Future, New York: Polity, 2016. See also David Shambaugh, ‘The Coming Chinese Crackup’, The Wall Street Journal, 6 March 2015, online at: http://www.wsj.com/articles/the-coming-chinese-crack-up-1425659198

Pei Minxin, ‘The Twilight of Communist party rule in China’, The American Interest, 12 November 2015, online at: http://www.the-american-interest.com/2015/11/12/the-twilight-of-communist-party-rule-in-china/

Mo Zhixu, ‘China’s Future: Unstable and Unsettled’, Chinachange.org, 16 April 2016, online at: https://chinachange.org/2016/04/06/chinas-future-unstable-and-unsettled/

Jeffrey Wasserstrom, ‘The Great Fall of China’ The Wall Street Journal, 28 March 2016, online at: http://www.wsj.com/articles/the-great-fall-of-china-1459206467

Peter Hartcher, ‘Is the Chinese Dragon losing its Puff?’, The Age, 16 March 2015, online at: http://www.smh.com.au/comment/is-the-chinese-dragon-losing-its-puff-20150316-1m0bx9.html