In recent years, Chinese leaders have acknowledged that the country’s famed rapid development has also resulted in increased social inequality, environmental degradation and community unrest. Official attempts to revivify elements of the Maoist heritage that began in Chongqing, the ‘red culture’ discussed throughout this volume, was one attempt to find a past ideological model to serve present day society. A sage from a much earlier period, Confucius, has also been promoted by President Hu Jintao as providing values for rebuilding social cohesion while maintaining secular authority. The search for paragons led some also to Laozi, the Taoist philosopher, as well as to one of his latter-day adherents and promoters, the celebrity Taoist priest Li Yi. In the late 2000s, Li Yi’s ‘temple spa’ outside Chongqing became a haven for the nouveau riche, who sought there spiritual balm for the anxieties of modern life – until, that is, Li’s spectacular fall from grace in late 2010.

A tourist poses in front of a statue of Confucius that appeared on 11 January 2011 on the eastern flank of Tiananmen Square outside the National Museum of China. It disappeared without explanation on 21 April the same year.

Photo: Danwei Media

On 11 January 2011, a 9.5-metre bronze statue of Confucius appeared outside the entrance to the recently refurbished National Museum of China along the eastern flank of Tiananmen Square in the heart of Beijing. China Daily reported that the sculptor, Wu Weishan, ‘meant to present Confucius as a peak in the history of Chinese philosophy and culture… When passers-by look at his eyes, they may feel a kind of spiritual communication with the ancient wise man.’ One such passer-by was also quoted approvingly: ‘Confucian wisdom transcends time and space. In my opinion, Confucianism is at the core of Chinese values. It can still guide us in daily life.’ Opinion about the statue was not, however, all positive. The prominent leftist website Mao Flag demanded its removal and in a People’s Daily online poll taken about a week after its unveiling, some sixty-two percent of the 820,000 respondents expressed opposition to it.

The statue of Confucius ‘internally exiled’ to the courtyard of the National Museum of China.

Photo: Geremie R. Barmé

Early on the morning of 21 April, the statue disappeared. The untoward arrival of the Sage, followed by his equally sudden departure, led to fevered speculation on Chinese blogs as well as in the international press about what it all might mean. Did the erection of the statue signal the final and complete rehabilitation of Confucius after the vitriolic attacks on him in earlier decades of the People’s Republic? Did its removal indicate a change of mind among the inner circles of the leadership? Could Confucius’s disappearance even be a response to the negative reaction of ordinary Chinese, as evidenced in the poll results? And perhaps most significantly, was the volte-face by the authorities a manifestation of a shift in the power balance between Party factions leading up to the leadership changes in 2012-2013?

Not surprisingly, the opaque nature of Chinese succession politics and the close control that the Communist Party maintains over information fueled idle speculation. People immediately saw in the fate of the Confucius statue an augury of Party factional politics. Its removal was viewed by some as being one more sign of the then increasing influence of Bo Xilai, the Chongqing Party Committee Secretary and member of the Politburo, famous for his ‘Sing Red’ campaign and support for the Maoist legacy in general, something discussed in other chapters. Following the 2008 Beijing Olympics ideological differences amongst China’s leaders became more evident. But while political reform has been mooted it is unlikely that the Chinese Communist Party could in the future rename itself the Chinese Confucian Party, a suggestion made only half in jest. Equally unlikely, though, is the idea that in the second decade of the twenty-first century the Party could genuinely contemplate a Maoist revival.

Confucius (Kongzi 孔子)

Many of the most important Chinese political, philosophical and literary figures of the twentieth century regarded Confucianism as the ideological foundation of a repressive and backward society and culture and an autocratic, hierarchical political system. They saw Confucianism as the root cause of China’s weakness: it fostered servility in the people, enforced inequality (including gender inequality) in society, was more concerned with the family than the individual, and entrenched rote learning and self-destructive, ritualistic behaviour rather than intellectual inquiry and rational action. The first major wave of anti-Confucianism was in 1919, as part of the progressive May Fourth Movement, which saw Confucianism as inimical to democracy and science. By the Cultural Revolution in the mid 1960s, the Communists further vilified Confucius as the chief representative of ancient China’s slave-owning aristocracy, calling him Kong Lao’er – colloquially ‘Confucius the prick’. In the early 1970s, the Party leadership linked him with Mao Zedong’s then arch-enemy and erstwhile closest comrade-in-arms Lin Biao in the ‘Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius’ campaign.

Confucius was born in the state of Lu – roughly equivalent to modern Shandong – in 551 BCE. He died in 479, long before China had been unified by the Qin. Best known as the author of The Analects (Lunyu 论语), a book of his sayings and recollections compiled after his death by disciples, he worked as a scholar official, first in Lu, then later for the rival states of Wei, Song, Chen and Cai. The legend has it that in each place he expounded his theories of good government and human relations, but remained disappointed that they were never put into practice.

After Confucius’s death his disciples, and their disciples, preserved and developed his ideas, forming different schools of interpretation. The Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) adopted ‘Confucianism’ as its legitimizing ideology. But Confucianism, also known as the ‘Teachings of the Scholars’ (Rujia 儒家), continued to change and adapt itself to differing circumstances in subsequent dynasties. The Confucianism that survived into the nineteenth century was deeply influenced by a form that had appeared in the Song dynasty (960-1279) and is usually called Neo-Confucianism (credited to Zhu Xi, 1130-1200) and the Ming-dynasty philosopher Wang Yangming (1472-1529).

In the twentieth century Confucianism continued to have its defenders, both in politics and philosophy. A stream of thought called ‘New Confucianism’ (as opposed to Neo-Confucianism) appeared in the Republican period. Developed outside the People’s Republic after 1949, it began to claim adherents in mainland China from the early 1980s. They reasoned that the moral verities of Confucianism could help fill the moral and ideological vacuums left by the collapse of state Maoism and construct a modern state untainted by undesirable Western liberal values. Outside the mainland, one of the main proponents of New Confucianism – which essentially justifies an authoritarian state – was Lee Kwan Yew of Singapore. His push for ‘Asian values’ during the 1990s exemplified this trend.

Beginning in the mid 1980s, the Communist Party allowed and occasionally encouraged the rehabilitation of Confucianism. Discussions of the relevance of Confucianism to modern problems have saturated academic and public spheres. From early in the new millennium Confucius became the name the Chinese government chose to represent China to the rest of the world, even calling the Chinese cultural and language learning centres being set up across the globe with state funding ‘Confucius Institutes’.

On 11 January 2011, a bronze statue of Confucius was erected outside the entrance to the newly renovated National Museum of China on the east side of Tiananmen Square. There was neither official explanation nor any ceremony. The leftist website Mao Flag (maoflag.net) objected, and published an article calling for its removal. Illustrating the article was an image of the statue with the character for ‘demolish’ (chai 拆) photo-shopped over it. On 21 April, the statue disappeared, again without any explanation in the media or from official sources. It reappeared in an internal courtyard of the National Museum.

Harmonious Confucianism

One thing is certainly clear: Confucianism in a form approved by the Party is alive and well in today’s China. It has attained a respectability unimaginable during the country’s revolutionary era. In its current anodyne form – far removed from the subtle and rigorous arguments of the Confucian philosophical tradition – China’s party-state uses the sage’s teachings to help justify repressive actions and policies. Much of the social and political coercion of recent years, topics discussed at length by Susan Trevaskes in Chapter 3, is pursued in the name of creating ‘harmony’ and an ‘harmonious society’. When President Hu Jintao launched the program to build an ‘harmonious society’ at the February 2005 meeting of China’s National People’s Congress, he proclaimed that: ‘As Confucius said, “Harmony is precious”.’ This allowed, and indeed helped to generate, a wave of enthusiasm for Confucius.

The statement, ‘Harmony is precious’ (he wei gui 和为贵) comes from the primary Confucian classic, The Analects. In that book, however, the line is not attributed to Confucius himself but to his disciple Youzi. It has gained slogan-like currency in contemporary Chinese. But the full sentence in The Analects is: ‘Harmony is precious when performing the rites.’

The ‘rites’ were the codified rules of behaviour that governed formal rituals, individual decorum as well as that of the family and strict regulations for the conduct of interpersonal relationships. But then perhaps Hu’s use of the adage betrayed the real meaning of China’s present politics of ‘harmony’: to make people behave according to a set of norms determined by officialdom and its changing priorities.

The background to Hu’s move to proclaim ‘harmony’ as the primary social good resulted from the realization that the benefits of thirty years of economic growth were distributed unevenly; a small number of people enjoyed extraordinary wealth while the vast majority still struggled. Social services such as medical care have become too expensive for many to afford, the cost of housing has skyrocketed, and the effects of pollution are appalling. Creating an harmonious society was meant to help alleviate these ills. Policies aimed at building a more equitable society encompassed undertakings to improve China’s ‘democratic legal system’, protect human rights, increase employment, narrow the wealth gap, improve public services, promote moral standards, and secure public order as well as protect the environment.

More cynical, and perhaps realistic, observers also see behind these noble sentiments a warning against any attempt to question or undermine the power of the Communist Party. Indeed, the invocation of Confucius and notions long ascribed to Confucian thought such as the importance of maintaining proper social hierarchies, the need for loyalty and respect towards those in superior positions, made Hu’s call for ‘harmony’ seem, for some, like a strident call for the shoring up of authoritarianism. Rulers in China from imperial times have consistently and morbidly feared ‘chaos’, understood as a collapse of social bonds and relationships, a state of turmoil, of upheaval and overturning, or even a challenge to their own authority.

Logo for the Confucius Institute, an organization intended to promote the party-state’s version of Chinese language and culture.

Source: Confucius Institute website at Chinese.cn

Along with the Party’s use of a repackaged Confucianism to further its current goals, the enthusiastic invocation of the Sage is also part of an effort to forge a new national image, both at home and overseas. If Confucius now represents ‘harmony’ and ‘peace’, these noble virtues are emptied of any particular relationship to his actual thought, except in the most diluted form. The Sage himself, meanwhile, has ended up as an amorphous symbol for Chineseness that can be deployed for almost any nationalist purpose. Despite the appearance and the disappearance of the Confucius statue, the ancient Sage as palimpsest is still a potent power in China: his name means everything, even as it means nothing in particular.

The Sage Put to Use

One of the first instances of Confucius being used as a national brand came with the establishment of Confucius Institutes. This state-funded program is ostensibly the equivalent of Germany’s Goethe Institute, France’s Alliance Française and Italy’s Dante Alighieri Society. Like them, Confucius Institutes are intended to promote internationally the study of the national language and culture. The first Confucius Institute opened in 2004 in Seoul. Now there are some 350 of these institutes in 105 countries, as well as another 500 ‘Confucius classrooms’ in schools. There are nine Confucius Institutes in Australia, located in tertiary education institutions, as is typically the case in most countries, with the number of school-based Confucius classrooms growing. Concerted opposition to the program has, however, limited their growth. Criticisms have focused on the possible threat to academic freedom they represent by being located in universities: topics sensitive to the Chinese government such as Tibet, Taiwan or Falun Gong cannot be discussed in the fearless way we expect to be the norm in academic institutions.

More problematic, Confucius Institutes are perceived as a tool of China’s soft power diplomacy. ‘Soft power’ refers to a state or other international actor attaining their objectives through such means as culture, education or reputation rather than through military or coercive measures. Another less well-aired but equally cogent criticism of the Institutes is that in their language programs, they promote a very particular view of what ‘Chinese’ is and how it should be written (that is, Putonghua 普通话, or ‘Standard Chinese’, and in simplified characters). This curriculum excludes the very many other forms of Chinese currently spoken in the Sinophone world (Cantonese, Shanghainese, Hokkien, etc.) as well as the traditional writing system, effectively rendering the language learner, in the words of one recent critic, ‘semi-literate’. Whatever the underlying politics of the Confucius Institute program, it should be clear that it has very little to do with Confucius himself. Indeed, students trained exclusively in their language programs would be unlikely to be able to read The Analects.

A leaflet for the Confucius Peace Prize, first awarded in 2010 as a riposte to the Nobel Peace Prize given to Liu Xiaobo.

Source: Baidu Baike

Confucius Institutes are only one example of the controversial appropriation of the philosopher’s name for institutions and events that have, or seek to have, official sanction. Perhaps the most egregious is the ‘Confucius Peace Prize’, an idea first proposed by one Liu Zhiqin, the chief representative of Zurich Bank in Beijing. Liu suggested the establishment of this prize as a response to the awarding in October 2010 of the Nobel Peace Prize to the dissident writer and thinker Liu Xiaobo. Liu Zhiqin’s advocacy of a new, Chinese-sponsored peace prize published in November 2010 began with a strident critique of the Nobel Committee:

The Nobel Peace Prize Committee won Liu Xiaobo while losing the trust of 1.3 billion Chinese people. They support a criminal while creating 1.3 billion ‘dissidents’ that are dissatisfied with the Nobel Committee… However, the Chinese people’s discontent or questioning will not change the prejudice of the proud and stubborn Noble Prize Committee members… it has become the mind-set of the current Westerners that they will oppose whatever China supports and support whatever China opposes. In order to make them change their mind-set, more appropriate ways need to be adopted…

The first Confucius Peace Prize was awarded in December 2010 to Lien Chan, Chairman Emeritus of the Nationalist Party and former Vice-president of the Republic of China on Taiwan. It was awarded in recognition of his famous 2005 trip to the mainland. Lien’s meeting with Hu Jintao on that occasion was the highest-level contact between the Communists and Nationalists since 1945, when Mao Zedong had met Chiang Kai-shek in Chongqing. Lien was chosen by the ‘Confucius Peace Prize Committee’ (described in the Chinese media as being an NGO) from a shortlist that is said to have included Bill Gates, Nelson Mandela, and the Chinese-government-endorsed Eleventh Panchen Lama. The director of Lien’s office commented on the prize: ‘We’ve never heard of such an award and of course Mr Lien has no plans to accept it.’ In September 2011, the Chinese Ministry of Culture announced that the prize had been cancelled. This was followed three weeks later by an announcement cancelling an alternative award – the Confucius World Peace Prize – that was to have been run by the China Foundation for the Development of Social Culture, an organization under the Ministry of Culture. Despite this, a second prize was awarded in 2011, this time to Vladimir Putin by the China International Peace Research Centre, a new Hong Kong registered organization headed by the poet Qiao Damo, who was a member of the original Confucius Peace Prize committee and who had apparently nominated himself for the 2010 prize. Like Lien Chan before him, Putin failed to appear at the award ceremony in Beijing. His prize was accepted in his stead by two Russian exchange students.

Another recent event in the world of Confucius appropriation, this one with strong government support, was the 2010 film Confucius starring the Hong Kong star Chow Yun-fat in the title role. It was supposed to open in 2009 – the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic, and the 2,560th of the birth of Confucius (according to the traditional dating). The première was delayed allegedly because the authorities feared that it would be overshadowed by the much more popular US film Avatar. Initially, the idea that Chow Yun-fat, a Hong Kong star who has frequently played gangsters, would play Confucius was met with skepticism – analogous perhaps to Sylvester Stallone being cast as Shakespeare. His performance was nonetheless one of the best things about the film, which The Guardian characterized as a ‘smug biopic’.

Declarations of Harmony

With Confucianism being given such a preeminent position in the public arena, there was an expectation that intellectuals would rally to the support of the cause. Perhaps the most famous person to bolster Confucianism in the mass media is Yu Dan, a professor at Beijing Normal University and celebrity interpreter of ancient philosophy. Yu came to fame as a result of her 2006 TV lectures on The Analects, which also became a bestselling book. Translated into English as Confucius from the Heart: Ancient Wisdom for Today’s World, Yu made the classic text into a self-help guide, a pop version of the Sage, his wisdom made accessible through anecdote and pre-digested life lessons. A blurb on the book cover asked:

Can the classic sayings of The Analects from more than 2500 years ago inspire insights today? Can they still stir up deep feelings in us? Addressing the spiritual perplexities that confront twenty-first century humanity, Beijing Normal University’s Professor Yu Dan – with her profound classical learning and her exquisite feminine sensibility – sets out to decode The Analects from the perspective of her unique personality…

Not long after Hu Jintao (mis-)quoted the sage, an annual ‘World Confucian Conference’ was established. The fourth of these was held in late September 2011 to coincide with Confucius’s traditional birth-date on the twenty-eighth of that month. The venue was Qufu, Shandong province, where the main Confucius Temple and ancient Kong Family Residence is located. In the previous year, in 2010, the Nishan Forum on World Civilizations was held at nearby Nishan, traditionally regarded as the sage’s birthplace. The Nishan Forum is dedicated to the cause of ‘dialogue between international cultures’, a dialogue in which ‘Confucianism’ is regarded as somehow being equivalent to ‘Chinese culture’ and ‘Christianity’ with ‘Western culture’. The keyword in all of these activities was, once again, the Communist Party mantra, ‘harmony’. Xu Jialu, the President of the Organizing Committee of the Nishan Forum (and a Vice-chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress), declared that the themes of the Nishan Forum were ‘Harmony with Diversity’ and ‘the Harmonious World’, its slogan ‘Harmony, Love, Integrity and Tolerance’. Furthermore, cross-civilizational dialogues would focus on ‘social responsibility, credit, tolerance and diversity, and harmonious coexistence.’ The Nishan Forum also promulgated a ‘Declaration of Harmony’, a set of motherhood statements that amounted to a version of Confucianism-lite.

Confucianism has by no means been the only one of China’s great philosophical traditions to enjoy an officially approved resurgence. Laozi, the founder of Taoism (Daoism), has yet to be honoured with a statue in Tiananmen Square or a peace prize, but his philosophical legacy, like that of Confucius, has in recent years been recast as an ideological bulwark and global marketing tool.

In October 2011, an International Taoism Forum was held at Hengshan, one of the five sacred Taoist mountains, in Hunan province. With representatives from Taoist organisations and temples throughout mainland China and from overseas (including Taiwan), as well as notable invited foreigners, this conference too released a formal declaration.

Laozi (老子, also rendered Lao Tzu)

Laozi (literally, ‘the Old Master’), the founder of Taoism (or Daoism), is traditionally regarded as having lived in the sixth century BCE. The short text that bears his name is also known as Daodejing (Tao-te Ching 道德经), or The Way and its Power. At barely 5,000 characters, it is written in a terse and frequently ambiguous style that has given rise to a long and varied tradition of commentary and interpretation. Archaeological discoveries from the 1970s onward have shown that the classic version of the text was just one of probably several versions that circulated in the centuries before the Common Era.

Records concerning Laozi date from long after his death and are not consistent. Sima Qian, the author of China’s first comprehensive history, The Records of the Historian (Shiji 史记), which was completed in 91BCE, presents three different and contradictory stories about him.

One famous story places Laozi as Court Archivist in the state of Zhou. At the age of 160 weary of court life he is said to have headed west on the back of a water buffalo. On his journey, the keeper of one of the passes out of the state recognized him and asked him to pass on his wisdom. The result was the Daodejing.

Whatever the true story of his life, by the second century CE, Laozi had been transformed into a god, Lord Lao, the Most High One. Zhang Daoling claimed to have received revelations from Lord Lao. Zhang is regarded as the founder of what some scholars refer to as ‘Religious Taoism’ to distinguish it from ‘philosophical Taoism’, popular in literati circles throughout Chinese history. The religion flourished in pre-modern China, several dynasties adopted it as their state creed. The imperial family of the Tang dynasty even claimed Laozi as one of their ancestors and included his book in the syllabus for the civil service examinations.

Buddhism entered China from India in the first few centuries of the Common Era. Buddhism and Daoism were in periodic conflict, criticizing and often ridiculing one another, which didn’t prevent them from borrowing each other’s ideas when it suited. One of the most potent stories the religious Taoists made up claimed that after Laozi had left China on his buffalo, he had ended up in India. Finding the natives there less intellectually able than his own people, he taught them what we might now call a ‘dumbed-down’ version of his teachings. Indian Buddhism, in this telling, is merely a popularized version of Laozi’s wisdom.

In modern times, Laozi’s book is widely regarded as an indispensable element of China’s philosophical heritage and remains a favourite text of intellectuals who see themselves as non-conformists. The religion of Taoism is one of the five official religions of China’s People’s Republic. Lord Lao is still worshipped in Taoist temples, where the Daodejing is recited like a sutra.

The Hengshan Declaration, like that from Confucian Nishan, made a claim that it had relevance for the whole globe, not just China. It promoted Taoist philosophy as a cure for humanity’s ills, be they inequality, conflict or environmental degradation. Like its Confucian counterpart, the Hengshan Declaration referred to ideas that while recognizable as Taoist were vulgarized to the point of parodic blandness. The Declaration ended with an admonition to: ‘Respect the Tao and honour Virtue for harmonious coexistence.’ It was hardly a surprise that the Hengshan and Nishan declarations strike the same note, given contemporary policy imperatives. Xu Jialu, the organizer of the Nishan meeting, was also present at Hengshan. He was interviewed at length on the themes of the forums on the program ‘Journey of Civilisation’ on national TV.

The 2011 Taoist Forum had been preceded by another in 2007, the International Tao-te Ching Forum, held jointly in Hong Kong and Xi’an. During that event the world record for the most people reading aloud simultaneously in one location was broken when 13,839 people recited the Tao-te ching, the famous Taoist classic, en masse in a Hong Kong stadium (this record was broken in May 2011 when when 23,822 people took part in a mass reading event at the Malatya Inönü Stadium, Turkey). The stated goal of the 2007 meeting was to investigate ways of constructing – no surprises here – ‘a harmonious society through the Tao.’

The organs of China’s party-state have appropriated Confucianism and Taoism in order to reinvigorate a discredited ideology, and a jaded polity, and to create an image of ‘civilized China’ for local and international consumption. However, such gestures inevitably have consequences far beyond those originally intended. Hu Jintao’s appeal to a transcendental Chineseness – an appeal accepted by the man passing by the Confucius statue who said: ‘Confucianism is at the core of Chinese values’ – also allows others with different agendas to gain credibility. It provides the space and rationale for clever entrepreneurs to tout themselves and their wares as ancient Chinese wisdom. Such charlatans exploit widespread contemporary ignorance of what ‘ancient Chinese wisdom’ really was. Their ignorance stems from earlier decades in which the Communist Party promoted cultural nihilism, purges and denunciations of the past and contempt for non-revolutionary education.

Taoism

While today’s officially endorsed Taoism buttresses the official ideology of social harmony, in earlier periods it was often a teaching that promoted an inner harmony par excellence – a balance between yin and yang, or between spirit, essence and qi. These ideas were not confined to Taoism, but Taoists were amongst their leading proponents. While ‘harmony’ has only reappeared in the last decade, a renewed focus on self-cultivation (xiuyang 修 养) – a rediscovery and contemporary recasting of complex ideas that stretch back into China’s earliest recorded history – has been in fashion since the 1980s. Usually considered as part of qigong practices, self-cultivation re-emerged following the suppression of Falun Gong in 1999, in a more regulated form. In recent years self-cultivation has become big business, a home-grown version of self-help culture that includes gurus, classes, retreats and diets. Adepts and devotees of the practice can become media stars, not to mention a good investment for canny proprietors. A Taoist priest by the name of Li Yi was both.

Fang Zhouzi 方舟子

Li Yi’s fraud was uncovered by China’s most famous investigative journalist, Fang Zhouzi. Fang is known as the ‘science cop’ since much of his media fame has come from exposing academic rather than religious fraud (he studied for a PhD in biochemistry at Michigan State University). He is known for his previous dogged pursuit of Xiao Chuanguo, a Professor of Urology at Wuhan’s Huazhong Science and Technology University. In 2005, Xiao’s university nominated him to the Chinese Academy of Science, but the Academy rejected this after Fang and his collaborators raised allegations that Xiao’s CV was questionable and his academic claims exaggerated. In response, Xiao sued Fang for defamation and published a bitter open letter that began:

An ugly bride eventually has to show her face to her in-laws. Fang Zhouzi, maybe you can hide for now, but you cannot hide forever. One day you will be brought to justice.

In August 2010, Fang was waylaid and bashed near his home in Beijing. Initially, gangsters were blamed for the assault but it soon came to light that Professor Xiao had hired thugs to beat up the journalist. The media soon dubbed Xiao ‘Professor Hammer’. He was gaoled for five and a half months by a local Beijing court in October 2010, not on charges of attempted murder as Fang had suggested but simply for ‘causing a disturbance’. Xiao was released from prison in March 2011.

Fang Zhouzi came to public attention again in early 2012 when he claimed that the famous Shanghai blogger Han Han had a ghost writer, claims Han Han vigorously disputed. Fang claims that he and his team have exposed over 700 cases of ‘falsification, corruption, and pseudoscience’.

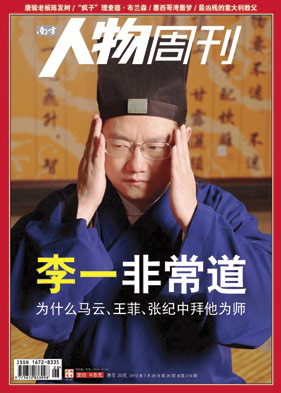

Taoist master Li Yi featured on the cover of Southern People Weekly. The headline reads: ‘The Extraordinary Tao of Li Yi: Why Do Jack Ma, Faye Wong, and Zhang Jizhong Acknowledge Him as Their Master?’

Source: Southern People Weekly

Li Yi made his first public appearance in 1990, not as a Taoist priest but as a performer in an acrobatic troupe whose members performed uncanny physical feats. Li claimed that he possessed ‘extraordinary powers’ (teyi gongneng 特异功能) – clairvoyance, telekinesis and the power of healing. He even claimed he could hold his breath underwater for two hours. It was a trick that got him onto national TV. In 1993, Li Yi expanded his repertoire opening a massage clinic. In 1998, he acquired control of a run-down Buddhist temple in the Jinyun Mountains outside Chongqing, a city that has featured frequently in this book. He renamed the temple the Palace of Intertwined Dragons and in 2006 Li formally took Taoist holy orders, though he had already been describing himself as a priest for some time. In June 2010, he was named a Vice-president of the National Taoist Association.

The Palace of Intertwined Dragons was a modern Taoist resort. It featured a version of Taoism updated and tailored for China’s nouveau riche, a populist version of venerable teachings just as etiolated as the mock-Taoism touted by the Hengshan Declaration. Conveniently located in the cool and picturesque mountains outside the famously sweltering megalopolis, well-heeled urbanites flocked to Li Yi’s temple-palace. As one observer noted, the temple provided ‘a new version of religious service to society teaching the newly wealthy and accordingly stressed-out class of upscale Chinese businessmen how to relax and keep themselves fit.’ It boasted all the features of a contemporary hotel, including a computer room and hot tubs as well as buildings for ‘massages, physical treatments, medical diagnoses, herbal prescriptions and exercise.’ Both Li Yi and his operation proved to be a resounding popular success. The press reported that over the course of a few years hundreds of thousands of people had attended Master Li’s courses and more than 30,000 people had become his disciples.

Li Yi’s business also benefited from the patronage of some of China’s A-list celebrities. Their number included the singer Faye Wong (who had sung the title song for the film Confucius), her husband, the martial arts actor Li Yapeng, the film director Zhang Jizhong and Jack Ma, founder and chairman of Alibaba.com (who would balance his interest in Taoism with his devotion to traditional Party culture – see the following chapter). The media fawningly reported their comings and goings. By 2009, the association of the celebrity couple Faye Wong and Li Yapeng with the Palace of Intertwined Dragons was being excitedly reported in Singapore where the media noted that they had only recently taken part in a nine-day retreat, during which they practised rigorous physical exercise, ate only bland food, listened to lectures on the Tao and spent hours transcribing scriptures, all in strict silence and avoiding physical contact. Li Yi’s celebrity reached something of an apogee when, in July 2010, the popular magazine Southern People Weekly devoted its cover story to him. The lead read:

The Extraordinary Tao of Li Yi: Why Do Jack Ma, Faye Wong, and Zhang Jizhong Acknowledge Him as Their Master?

Li also benefited from the assistance of a professional spruiker, a China Central Television presenter by the name of Fan Xinman, who wrote a blog devoted to the doings and sayings of the Master. In 2009, the first tranche of these blog posts was collected into a book called Are There Immortals in Our Generation? (Fan Xinman also happened to be the wife of Zhang Jizhong, the film director mentioned above.)

A little over a month later the bubble burst. Another member of the ‘Southern’ media stable, the influential but controversial magazine Southern Weekly exposed Li Yi as a fraud. They revealed his famous special powers to be clever trickery. People rushed to distance themselves from the discredited trickster and his famous disciples issued media denials that they had anything to do with a man now notorious for chicanery, phoney academic affiliations and shady financial dealings. Shortly after the media storm broke, Li Yi left the Jinyun Mountains and Chongqing in disgrace. At the time of writing he has yet to resurface.

Elsewhere in this volume we have discussed the differences between the Chongqing and the Guangzhou models and how they have played into the political, social and cultural life of contemporary China. The ‘Li Yi case’ is an example of another facet of this broader competition – a media trickster who was closely involved with China’s new celebrity culture and self-promotion based in the hyperbolic environment of the boomtown of Chongqing, Li was undone by investigators who published their exposés in the (relatively) liberal media of Guangzhou.