Film poster for the 2009 film made as a homage to the party-state on the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

Source: The Founding of a Republic, poster

‘The China Story’ as told by the Chinese authorities is a grand romantic narrative of struggle, progress and socialist transformation. It is a glowing history of how the Party has brought about the ‘great renaissance of the Chinese nation’. On the occasion of the celebration of the sixtieth anniversary of the People’s Republic in 2009, China’s President Hu Jintao repeatedly cited this phrase, first used by Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin a decade ago. Hu reprised it when marking the centenary of the 1911 Xinhai Revolution on 9 October 2011.

The state-ordained China Story begins with the decline in power, economic might and unity of the Chinese world from the eighteenth century. It then moves through the century of humiliation (roughly 1840-1949) at the hands of Western and Japanese imperial powers and culminates in the birth of a New China and the two acts of ‘liberation’ (1949 under Mao and 1978 under Deng Xiaoping). It is a story of national revolution, renewal and vigour that, crucially, cleaves to Mao Zedong’s leadership, career, thought and politics.

This univocal, uni-linear story denies the complex of what would be better described as ‘China’s Stories’ as well as the myriad nature of China’s modern history. In the past the Chinese party-state asserted itself as the sole authority on what was happening on the ground in China. If some individuals or groups claimed that official version was at variance with their own experiences, the authorities would dismiss such cavils as partial, biased, ill-informed views that pandered to anti-government forces and ‘anti-China’ interests. According to one formula, the party-state could ‘see far ahead from its privileged viewpoint’ (gaozhan yuanzhu 高瞻远瞩): informed as it was by a Marxist-Leninist worldview and perspective on long-term historical trends and in-depth local knowledge, its view alone represented Chinese reality as well as the direction in which the country was moving.

Corruption and Privilege

Although recent commentators have claimed that China has become increasingly corrupt in the last decade, and indeed a ‘mafia-state’ has developed, critics of one-party rule made similar charges from before the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. In the early 1940s, the writer Wang Shiwei famously criticized Party leaders at the Communist base of Yan’an for their special privileges, grades of food, clothing and accommodation. He was denounced as a Troskyite and eventually beheaded.

After the founding of New China, an elaborate system of ‘privileged supply’ (teshu gongying 特殊供应, or tegong 特供 for short) was introduced from the Soviet Union. A network of restricted-access shops and farms was created to cater to the needs of the Party nomenclatura, a vast body of Party functionaries, bureaucrats and their families divided into twenty-four grades. Cars and telephones were among the special privileges limited to the fortunate few. Mao Zedong and other leaders enjoyed these along with (for the time) luxurious villas located at the most scenic places in the country. The central party-state leaders themselves ruled from a former imperial pleasure ground in the centre of Beijing, Zhongnanhai, the ‘Lake Palaces’.

When Mao called on intellectuals and others to help the Party ‘rectify its work style’ in light of criticisms of party rule in the Eastern Bloc in 1956, many spoke out against the secretive privileges and power of Communist Party cadres. In 1966, when Red Guard rebels were allowed to attack the Party they identified privilege, corruption and abuse of power as the greatest enemies of the revolution. Again, at the end of the Cultural Revolution, when there was a period of relatively free criticism of the Party, privilege and corruption were identified as the greatest threat. In 1989, during a nation-wide protest movement, some protesters released a detailed account of the connection between Party bureaucrats, their children and new business ventures that had sprung up during the early stages of reform. One of the Party leaders directly blamed for the corrupt nexus between Party power, private enterprise and global capital was Zhao Ziyang, later ousted as Party General Secretary.

China’s Party leaders echo Mao Zedong’s old refrain that corruption can lead to the collapse of the Party and the nation when they bewail the rampant corruption of recent years. In the 2012 attacks on Bo Xilai and his wife, Gu Kailai, a system of cronyism and corruption endemic in the Chinese one-party state, has been protected while the couple were made an object of national vilification.

Party leaders and their families, be they in Beijing or in the provinces, continue to enjoy food produced at special organic farms, dedicated water supplies, luxurious accommodation, clubs and villas and a range of other perks. As in other areas of its activities, the Party is unaccountable. None of its self-allocated privileges are open to public scrutiny and budgetary allocations are a carefully guarded state secret.

In the 2009 film ‘The Founding of a Republic’ (Jianguo Daye 建国大业) produced to celebrate to sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic, Chiang Kai-shek says: ‘If we fight corruption, we’ll destroy the party; if we don’t fight corruption, we’ll destroy the nation’ (fan fubai jiu wangdang, bu fan fubai jiu wangguo 反腐败就亡党;不反腐败就亡国). The party he was referring to was the Nationalist Party not the Communists, but many viewers of the film posted comments online saying that the words were perfectly applicable to contemporary China.

Officially, at least, the party-state authorities ‘oppose corruption and espouse frugality’ (fanfu changlian 反腐倡廉).

Dissidents argued against this mainstream view. But until the advent of the Internet, their opinions didn’t travel far beyond their own circles and a few engaged outside observers. While they might be published in a sensation-hungry media (Hong Kong, Taiwan, or international) their ability to reach wider audiences was limited by a strictly controlled media and publishing industry at home. The rise of the Internet, blogs and, more recently, microblogs, has democratized information (as well as misinformation), which can circulate in new ways that both challenge the Chinese state and our understanding of this vast, complex and ever-changing country. The China Story is now more accessible, nuanced, detailed – and out of control – than ever before.

The front page of The Chongqing Economic Times 20 April 2012: in a turn away from the formerly robust Red Campaign the paper’s headline praised major companies in Chongqing that through the taxes have proved that they are ‘the backbone of Chongqing’s economic development’.

Source: Chongqing Economic Times

Front page of People’s Daily on 12 April 2012 featuring an article urging readers to ‘Conscientiously maintain the good situation of reform, development and stability’. The article also states that the broad masses of Chinese cadres and people strongly support the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party’s decision to investigate Bo Xilai.

Source: People’s Daily

The China Story, as presented in this volume, is that of a formerly underground political party that recast itself, first as a revolutionary national leadership in the late 1940s and then as a legitimate government in power (zhizhengdang 执政党) some three decades ago. For all the paraphernalia of state power, to this day its internal protocols and behaviour recall its long history as a covert, highly secretive and faction- ridden organisation. Even under Mao, some commentators called China a ‘mafia-state’.

This aspect of the party-state was thrown into sharp relief in February 2012 when the former Deputy Mayor of Chongqing, Wang Lijun a man previously famed for having led the attack on that city’s own ‘mafias’, was ordered to undergo an extended period of what was euphemistically termed ‘therapeutic rest’ (xiujiashi zhiliao 休假式治疗) following his appearance at, and subsequent disappearance from, the US Consulate in Chengdu, Sichuan province. (Soon after, ‘treatment’ came to include detention and investigation.) Then, on 15 March, his erstwhile boss and local Party leader, Bo Xilai, was dismissed from his various positions and put under investigation himself.

A Two-track Story

Since the end of the Cultural Revolution, approximately once every decade cataclysmic events in China have led to a clash of views about the country and its rapid transformation. In 1979, the closing down of the Xidan Democracy Wall, where people had aired complaints against the Party and the Chinese government (including those who, like the electrician Wei Jingsheng, warned that to be a modern nation China need democracy), marked the beginning of the bifurcated or ‘two-track’ understanding of contemporary China. Ever since, even as the country’s remarkable economic growth has been hailed locally and internationally, the country’s persistent and often draconian one-party rule has elicited constant critique.

The nationwide protest movement of 1989 and its violent suppression on 4 June entrenched this two-track understanding of China. The Chinese authorities’ version of the story is that demonstrators in dozens of cities were witless tools in the machinations of plotters and schemers, themselves serving US-led international efforts to undermine the Communist Party, weaken China and thwart its re-emergence as a major global power. Others call it a pro-democracy movement that was brutally suppressed by an armed dictatorship.

Screenshot of the terse Xinhua News Agency announcement of the Party’s investigation into Bo Xilai, 10 April 2012.

Source: Xinhua

It is not only the Chinese party-state, but average Chinese and patriots of all persuasions, however, who are prone to attack ‘the West’ for its ignorance of Chinese reality in that case and others. The constant flow of negative stories about mainland China in the non-mainland Chinese press in Hong Kong and Taiwan is harder for the party-state to dismiss. Harder still is it to deny the lived realities and self-told stories of people who can increasingly speak out for themselves and have their voices heard in no small part thanks to the Internet.

Two other notable manifestations of the two-track story of China occurred in 1999. The first happened on 25 April when thousands of practitioners of the Falun Gong religious sect surrounded Zhongnanhai, the seat of the Chinese party-state. This was followed later in the year by repression of the sect and resulting international disquiet about religious freedom and human rights abuses. The second happened on 7 May, when NATO forces bombed – mistakenly it was claimed – the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade, killing three Chinese journalists. And then there was March 2008, when protests and a riot in Lhasa led to an uprising throughout Tibetan China. This was another moment when mainstream international media reporting in particular clashed with China’s official account of reality.

More recently, in February-March 2012, speculation and rumour about the fall of Bo Xilai were rife. The Chinese authorities resorted to their default mode of high dudgeon to aver that Western accounts of Bo’s fall alleging unprecedented levels of corruption, nepotism and Party cronyism, lacked objectivity. But the speculation was hardly limited to ‘the West’. The ambient political hysteria and rumour-sharing sparked by ructions in China’s political life is the by-product of the secretive Chinese party-state itself and are also common in China. The opaque Chinese political system and its censorious vigilantism with regard to the guardianship of The China Story are facing unique challenges from the People’s Republic’s new-found prosperity, global role and international heft.

Writing in June 2012, the activist artist Ai Weiwei, a man who has featured in the pages of this Yearbook, saw in the fate of three very different public figures, a shared condition:

Reflect on Bo Xilai’s case, [the blind lawyer] Chen Guangcheng’s and mine. We are three very different examples: you can be a high Party members or a humble fighter for rights or a recongnised artist. The situations are completely different but well have one thing in common: none of us has been dealt with through fair trials and open discussion. China has not established the rule of law, and if there is a power above the law there is no justice.

A Cyclical History

‘Go Among the Masses; Eschew Empty Talk’, in Mao Zedong’s hand. A modern-day sculpture at the original headquarters of the Xinhua News Agency and Liberation Daily on Qingliang Shan 清凉山, Yan’an, Shaanxi province.

Photo: Geremie R. Barmé

Critics of the Communist Party-centric China Story often decry it as being politically bankrupt. Many countries and their governments strive to create a unifying narrative that transcends quotidian realities related merely to economics, wealth creation and financial markets. China is no different. Now that country has achieved many of the formal goals of a revolutionary century and China has become a strong and relatively wealthy nation, Chinese from all walks of life have increasingly questioned the rationale for the continuation of the one-party state. They question its ability to oversee a restive nation encompassing divergent needs and interests. Maintaining the status quo while pursuing economic and social transformation by the old methods of police force and political coercion is a fraught, and hugely costly, exercise, as we have noted throughout this volume.

On 4 July 1945, Mao Zedong asked the educator and progressive political activist Huang Yanpei (1878-1965) what he had made of his visit to the wartime Communist base at Yan’an in Shaanxi province. Huang lauded the collective, hard-working spirit evident among the Communists and their supporters. But he expressed his doubts about whether the wartime frugality and solidarity could last. He predicted that the revolutionary ardour of the Communists could well wane if they ended up in control of China, and wondered out loud whether the endemic political limitations and blemishes of earlier Chinese regimes would return to haunt the new one, despite the best efforts of its committed idealists. Would autocracy, cavalier political behaviour, nepotism and corruption once more come to rule over China? Huang said he could see no way out of the ‘vicious cycle’ of dynastic rise and collapse, though he certainly hoped that Mao and his followers would be able to break free of the wheel of history.

In response, Mao declared unequivocally:

We have found a new path; we can break free of the cycle. The path is called democracy. As long as the people have oversight of the government then government will not slacken in its efforts. When everyone takes responsibility there will be no danger that things will return to how they were even if the leader has gone.

Following the 4 June 1989 suppression of a protest movement that had been characterized by inchoate demands for democracy and greater freedom, Mao’s remarks on breaking free of the vicious cycle of the past were dutifully recalled by pro-Party mass media historians. During Chinese Lunar New Year celebrations in February 2011, a group calling itself the Fellowship of the Children of Yan’an recalled Mao’s 1945 declaration that the Communists would lead China away from the tradition of autocracy and the cyclical history of the past. At what had become an annual gathering, the Fellowship warned that the party-state faced a momentous task, that of realizing the promise of Yan’an made some seventy years earlier. At their meeting they canvassed a document in which they called for major structural changes including the implementation of substantive democratic reform within the Communist Party.

The Children of Yan’an believed that they were well within their rights to offer their policy advice to the Party, an organization which many of their parents had contributed to building both before and after 1949. The members of the Children of Yan’an were predominantly descendants of men and women who had lived and worked in the Yan’an Communist Base in Shaanxi from the 1930s to the 1940s, as well as the progeny of the Party who were born and educated in Yan’an. Their outspokenness was a sign that China had entered a new era of ideological uncertainty, social anomie and open political contestation reminiscent of that which had lead to the chaos and suppression of 1989.

Hu Muying, daughter of Hu Qiaomu, a Party wordsmith par excellence and Mao Zedong’s one-time secretary (Deng Xiaoping called him ‘The First Pen of the Communist Party’) has led the group since 2002. In 2008, the Fellowship expanded its membership to include others without any direct link to the old Communist base. Henceforth, the Children of Yan’an would include anyone who wanted to collaborate under its banner and support its vision: ‘to inherit the revolutionary tradition, glorify the Yan’an spirit, build camaraderie with the children of the revolution, sing the praises of the national ethos and to work in various capacities for the old revolutionary areas, ethnic regions, the nation’s frontiers and impoverished areas.’

Yan’an 延安

Yan’an is a once-isolated town in the barren mountains of northern Shaanxi province. Celebrated as the ‘cradle of the revolution’, it was the last station on the Long March, becoming the Communist Party and Red Army’s base from 1936 to 1948. Many of the policies and systems that the Chinese government employs to this day were first articulated by Mao and established at Yan’an. Much early Communist iconography relates to Yan’an, where the leadership, soldiers and camp followers, including some prominent urban intellectuals, film stars and foreign fellow travellers like Edgar Snow and Agnes Smedley, lived and worked in the cave dwellings common to the locality in an atmosphere of austere but sociable egalitarianism.

In 1984, some of the children of Communist Party members who were born or grew up there set up an organization that now calls itself ‘Children of Yan’an’. The group is dedicated to realizing the ideals that their parents devoted themselves to in the heyday of the revolution.

The Children of Yan’an

At the 2011 Lunar New Year meeting, Hu Muying declared:

The new explorations made possible by Reform and the Open Door policies [inaugurated in 1978] have, over the past three decades, resulted in remarkable economic results. At the same time, ideological confusion has reigned and the country has been awash in intellectual currents that negate Mao Zedong Thought and Socialism. Corruption and the disparity between the wealthy and the poor are of increasingly serious concern; latent social contradictions are becoming more extreme.

We are absolutely not ‘Princelings’, nor are we ‘Second-generation Bureaucrats’. We are the Red Successors, the Revolutionary Progeny, and as such we cannot but be concerned about the fate of our Party, our Nation and our People. We can no longer ignore the present crisis of the Party.

Hu went on to say that through the activities of study groups, lecture series and symposiums the Children of Yan’an had formulated a document that, following broad-based consultation, would be presented for the consideration of the authorities in the lead up to the Communist Party’s late-2012 Eighteenth Party Congress. She said:

We cannot be satisfied merely with reminiscences nor can we wallow in nostalgia for the glories of the sufferings of our parents’ generation. We must carry on in their heroic spirit, contemplate and forge ahead by asking ever-new questions that respond to the new situations with which we are confronted. We must attempt to address these questions and contribute to the healthy growth of our Party and help prevent our People once more from eating the bitterness of the capitalist past.

In essence, the document drafted by the Children of Yan’an and publicized by them in the lead up to the politically momentous 2012 Party Congress, called for a revival of the legacy of the revolutionary past and for the recognition of a left-wing faction within the Communist Party itself.

Since 2008, the Party has expended considerable energy on silencing or sidelining liberal ideologies in China. The sentencing of the writer Liu Xiaobo, later Nobel laureate, on Christmas Day 2009 and the detention of the artist Ai Weiwei in April 2011 are the two highest-profile examples of these efforts. As the contributors to this volume have noted, it has also expended considerable energy in containing civil unrest, NGO activism, Internet agitation and a range of demands from dissenting thinkers advocating western-style democratic reform (in particular during 2011 as a result of the Arab Spring). So it is significant that those inside the Party who still identify with its Maoist leftist heritage were also actively agitating for reform and for a kind of internal Communist Party ‘democratization’, even if this particular version of populist democracy within an autocratic oneparty schemata may appear to be less than attractive.

Also noteworthy, if not unsettling, was the fact that among the key speeches and documents produced by the Children of Yan’an in recent years there has been scant importance placed on China’s burgeoning global influence, its enmeshment with the international economic order or awareness of regional concerns about the country’s rapid military build-up and the impact of its intermittent bellicosity.

Red Songs

On 20 April 2011, Guangming Daily reported that Bo Xilai’s Chongqing government had drawn up a list of thirty-six ‘Red Songs’ that party-state cadres and the masses should learn to sing as part of the ‘Sing Red, Strike Black’ campaign (see Chapter 3). Not all the songs were ideological in nature – some were merely popular tunes familiar to older people who grew up before Chinese popular music came to be dominated by singers and tunes from Hong Kong and Taiwan. The thirty-six songs on the list were:

- Moving Towards Rejuvenation 走向复兴

- Flag Fluttering in the Breeze 迎风飘扬的旗

- The Most Beautiful Song is for Mother 最美的歌儿唱给妈妈

- Concerned about the common people 情系老百姓

- China I sing for you 中国我为你歌唱

- Nation 国家

- Water chestnut flowers bloom on the southern lake 南湖菱花开

- The romance of the red flag 红旗之恋

- Happy days 喜庆的日子

- The taste of home 家乡的味道

- Loving each other devotedly 相亲相爱

- Love China 爱中华

- Let’s go China! 加油中国

- A good lad must become a soldier 好男儿就是要当兵

- I want to go to Yan’an 我要去延安

- Two sides of the Straits, one family 两岸一家亲

- On the sunny road 阳光路上

- Ballad of Lugou 卢沟谣

- The skies above us 我们的天空

- Horse wrangler 套马杆

- Pursuit 追寻

- So beautiful tonight 今宵如此美丽

- Spring ballet 春天的芭蕾

- My sister forever 永远的姐姐

- Power inside your heart 心中的力量

- If I were you 假如我是你

- Drink a toast to love 为爱干杯

- So good 多好啊

- Rain in my hometown 故乡探雨

- You are a hero 你是英雄

- Long live the motherland! 祖国万岁

- Red and green 红色绿色

- That piece of red land 那一片红

- Nostalgia 圆圆的思念

- My snowy mountain, my sentry post 我的雪山我的哨卡

- Worried about home 家的牵挂

This particular list did not include the song ‘Without the Communist Party, There Would Be No New China’ which was a standard item in Chongqing’s ‘Sing Red’ campaign.

Without the Communist Party,

There Would Be No New China

没有共产党就没有新中国Without the Communist Party, there would be no new China

Without the Communist Party, there would be no new ChinaThe Communist Party toiled for the nation

The Communist Party, unified, saved China

It pointed to the road of people’s liberation

It led China towards the light.

It fought the War of Resistance for over eight years

It has improved people’s lives

It built a base behind enemy lines

It carries the benefits of democracy

It practises democracy, whose benefits are manyWithout the Communist Party, there would be no new China

Without the Communist Party, there would be no new China

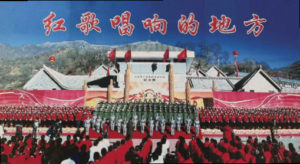

The Red Chorus

The Children of Yan’an declared that China’s new political talent could be found among the masses, in particular among the enthusiastic Party faithful. They claimed, for instance, that the ‘Sing Red’ campaign of Chongqing that was subsequently encouraged by the Party nationwide, had led to the discovery of the kind of enthusiastic younger Party stalwarts who would ensure the continuation of the Communist enterprise long into the future. In the 1960s, Mao Zedong had warned that after his demise people would inevitably ‘wave the red flag to oppose the red flag’. Now it would appear that the Children of Yan’an were using their very own red flag to oppose the red flag of economic reform that, since 1978, had itself been employed to oppose the red flag of Maoism.

‘The Place Where Red Songs First Resounded’. A poster celebrating the location where the song ‘Without the Communist Party, There Would Be No New China’ was written at Xiayun Ling 霞云岭, Hebei province.

Photo: Geremie R. Barmé

Red culture has formed the audio-visual backdrop to mainland Chinese history since the 1950s, and to some extent since the Japanese War period of the 1930s and 40s. After the end of the Cultural Revolution, it was reduced to little more than a disco-fication of Revolutionary Model Operas until after the 1989 protest movement. Following the suppression of that nationwide mass uprising against one-party rule and media control, the Communist Party used police force, indoctrination, re-education and cultural ‘soft power’ to reassert its authority, reviving Red Culture in the process. For a period, the momentum for further economic and social change of the 1980s was lost. Then, with his inspection Tour of the South in 1992, Deng Xiaoping encouraged further radical change that led to unprecedented opportunities for people to improve their living standards, and the Red Culture movement subsided once more. When, in early 2012, Deng’s Tour was recalled, commentators remarked that China again faced a stark choice: to carry out further systemic reforms that would unleash greater creativity and future prosperity, or to maintain the satus quo allowing thereby entrenched interest groups to advance a form of crony capitalism under the umbrella of party-state protection. Others would argue that a hyper-cautious collective leadership served China well, allowing the country to maintain stability and steady growth in a period of global fiscal uncertainty.

As we have noted in this book, in early 2012, the complex negotiations surrounding the power transition of 2012-2013 were thrown into sudden relief when Wang Lijun, until then a key ally of Bo Xilai in his ‘Sing Red, Strike Black’ campaign from 2009 fell from grace and made an abrupt and mysterious visit to the US Consulate in Chengdu, where he unsuccessfully sought asylum. Wang’s fall led to wild speculation about the fate of Bo Xilai and the role of ‘Princelings’ in Chinese politics. Some commentators believe that the ‘Red Culture’ campaign itself would be imperilled by this latest shift in the country’s power politics. Yet, while other forms of resistance to the Party’s current policies remain effectively outlawed, the red heritage of the Maoist era can provide another means by which to challenge the status quo.

Red Rising

The Children of Yan’an concluded their February 2011 plea for Party reform by referring back to Mao Zedong’s July 1945 exchange with Huang Yanpei in Yan’an. They reminded their readers of Mao’s belief that the Party had identified the final solution to China’s historical trap:

We have found a new path; we can break free of the cycle. The path is called democracy. As long as the people have oversight of the government then government will not slacken in its efforts.

In no uncertain terms the Children of Yan’an now declared:

We are calling on the whole Party to take a substantive step in this direction.

Not only had the Children of Yan’an formulated a manifesto and begun agitating for political reform, for in their pursuit of a Maoist-style ‘mass line’ they reportedly made tentative contacts with grass-roots organizations and petitioner groups in and outside Beijing. For left-leaning figures in contemporary China to engage in such pragmatic, and non-hierarchical, politics was highly significant, and alarming for the authorities.

Creative Industries and the Party’s October 2011 Decision on Culture

In 2001, a book by the creative industries specialist John Howkins appeared under the title The Creative Economy: How People Make Money From Ideas, that same year the Department of Culture, Media and Sport in the United Kingdom produced a document called ‘Creative Industries Mapping Document’. Together they assured the place of ‘creative industries’ in the minds and hearts of urban planners and bureaucrats across the globe.

Over the past decade as the Chinese government has pursued a combination of state directed economic reform and neo-liberal social experimentation it has absorbed ideas such as those related to ‘creative industries’. In the process of urban planning and renewal, for instance, since 2004 it has developed ‘creative cultural zones’ (wenhua chuangyi chanyequ 文化创意产 业区) and official documents emphasize the importance, and economic value, of the creative economy. Together they form part of a strategy to make uplifting anodyne socialist culture and entertainment part of China’s very own ‘cultural industries’ (wenhua chanye 文化产业).

In October 2011, the Seventeenth Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party concluded its Sixth Plenary Session at which it adopted a new set of guidelines for improving the nation’s cultural soft power and promoting Chinese culture. A major document on cultural issues was issued for detailed study and implementation throughout the nation and Hu Jintao’s keynote speech on the subject was widely reproduced. In that speech he emphasized the need for China to become a cultural superpower and to ensure the regulation of the cultural industry. He also pledged to redouble efforts to promote the ‘healthy and positive development’ of the country’s Internet culture.

In the wake of the events of February-March 2012, the Children of Yan’an gradually fell silent. Even before Bo Xilai’s March ouster, when they had met again to welcome in the Year of the Dragon at Chinese New Year in February 2012, they refrained from making further calls for internal Party reform, although in private some of their members expressed despair about the fate of the Party and the future of the nation.

Even in power, Mao Zedong frequently spoke about the dangers of bourgeois restoration and revisionism. He declared a number of times that he would have to go back into the mountains to lead a guerrilla war against the power-holders, indeed that rebellion was justified. In contemporary China heated discussions about the legacy of revolutionary politics continue in the cloistered security of academic forums; but Mao’s guerrilla spirit of rebellion, the active involvement with a politics of agitation, action and danger, are part of a red legacy that seem long forgotten. Restive farmers and workers may cloak themselves in the language of defunct revolution, but the evidence suggests that their metaphorical landscape is a complex mixture of traditional cultural tropes and an awareness of modern rights.

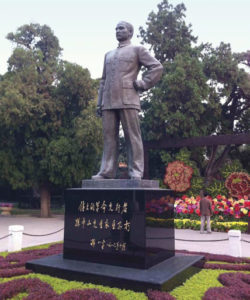

Red Eclipse

Sun Yat-sen (Sun Zhongshan, 1866-1925), the ‘father of the Republic of China’, who is recognized as a progressive revolutionary leader on both sides of the Taiwan Straits. This statue is located at the entrance to Zhongshan Park immediately to the west of Tiananmen Gate, Beijing.

Photo: Geremie R. Barmé

One of the most abiding legacies of Red Culture is the paradigm of the Cold War. Cold War attitudes and rhetoric are easily applied to the tensions between the People’s Republic of China and its neighbours as well as other nations with which it finds itself in conflict. The use of such rhetoric by the party-state and those in its thrall (from state think tank apparatchiki and a swarm of left-leaning academics to semi-independent media writers) of course encourages a response from the other side in any given stoush.

Since 2009, rhetorical clashes of this kind, some quite aggressive, have revolved around such topics as climate change, US arms sales to Taiwan, the valuation of the Renminbi, Internet freedom, territorial disputes in the South China Sea, Sino-Australian relations, as well as ongoing disturbances in Tibet and Xinjiang. In regard to these issues – and here we are concerned with Chinese rhetoric, not the substantive matters involving different national and economic interests – the default position of the Chinese party-state remains that of the early Maoist days when conspiracy theories, class struggle and overblown rhetoric formed the backdrop to any official stance. This is not to underplay the importance of real and ongoing clashes of national interests, worldviews, or political and economic systems, but simply to make the point that the way in which the party-state responds is very much dictated by the official parameters of The China Story.

Many questions remain as yet unanswered. Have revolutionary politics and ideology lost their traction in The China Story as the fall of Bo Xilai and the eclipse of red culture might indicate? Has the neo-liberal turn of Chinese statist politics in the decades of reform reshaped The China Story around a concocted and self-interested ‘Chinese race’, in which the main narrative is that of a nationalistic rise to superpower on the world stage? Or, do the various red legacies that date from China’s Republican era (be they communist, socialist or social-democratic) still contribute something to the ways in which thinking Chinese, in and out of power, contemplate that country’s future direction? Can a left-leaning legacy distinguish itself from a failed Maoism or Red Culture as entertainment? Or is Maoism and its panoply of language and practices the only viable source of resistance to the continuing spectre of Western imperialism? How do the discourses of universalism, as well as of economic and human rights fit into The China Story today?

This book has attempted to account for some aspects of The China Story over recent years. It is inevitably a limited and narrowly focused effort. We hope this first China Story Yearbook does, nonetheless, make accessible to a broad and engaged public some of the key issues, ideas and people important in China today.

For the Children of Yan’an and those of a more general leftist persuasion – those who were intellectually or sympathetically retro-Maoist or neo-Marxist, the red rising of recent years seemed to offer a glimmer of hope, a chance to recapture some of the lost ethos of China’s socialist possibility. Despite their objections to party-state policies that helped enrich the few, there was within this disparate group a broad endorsement of state power. The strong state, or what we call throughout this volume the party-state (dangguo 党国) was seen as being the essential guarantor of Chinese unity and economic strength.

We have noted the concern expressed by economists and journalists, thinkers and web activists that the social and economic transformation of China has, in recent times, been bedeviled by an increasingly assertive state and the vested interests represented by a nexus of party-state-business concerns. This situation is summed up in the expression ‘the state has advanced while the individual has been in retreat’ (guo jin min tui 国进 民退).

Xu Jilin, a prominent Shanghai-based intellectual historian, has called this version of Chinese cultural-politics a form of ‘statism’ (guojiazhuyi 国家主义). He has noted its previous, malevolent incarnations in twentieth century Europe, and warned that behind the vaunted ‘China Model’ lurks an unaccountable form of authoritarianism. Gloria Davies, a contributor to the present volume, has noted that: ‘In his robust critique of statism… Xu Jilin has argued that because it privileges an ideal scenario of responsible governance, statism is constitutively skewed toward legitimizing authoritarian rule. As a consequence little consideration is given to protecting individual rights and freedom of speech and association as guaranteed in the Chinese constitution.’

Among a myriad of dilemmas facing China in its post-transition age, it is that of the polity itself that remains contested. At the same time, the contemporary unitary party-state of the People’s Republic of China confronts the liberal market democracies of the world with the reality of a resilient state, a liberalized guided economy and a form of harsh paternalism. It is this particular Chinese ‘national situation’ (guoqing 国情) and what it means domestically, regionally and on a global scale that will be the focus of China Story Yearbook 2013, the title of which is: Civilising China.