For graduates in search of a job in China, March and April are traditionally the busiest hiring season. This golden window of opportunity has even acquired the nickname ‘golden March, silver April’ 金三银四. But this year’s job-finding season proved exasperating for many, with the National Bureau of Statistics reporting that in March 2023, unemployment among urbanites between the age of 16 to 24 had risen from 18.1 percent in the previous month to 19.6 percent. This means that nearly 1 in every 5 young people living in cities are jobless.

The situation is made worse by the rising number of college graduates. According to Global Times, higher education enrolment increased from 30 percent in 2012 to 57.8 percent in 2021. In 2023, a record number of 11.58 million students are expected to graduate from higher education institutions in China and entre the job market.

Disconcerted by the difficulty of finding employment despite working so hard for their degrees, China’s jobless graduates have turned to the internet to vent their frustration and find support among those experiencing similar hardships. In early March, a video went viral on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, of a graduate weeping and questioning the point of her university education after over 800 job applications, 30 job interviews — and still without a job. In the same month, a comment on Weibo resonated with millions:

People say education is a stepping stone towards something better, but lately I found it to be a high platform from which I can’t climb down. It is the scholar’s gown that Kong Yiji refuses to take off.

Kong Yiji is the title as well as the central character of a short story by Lu Xun 鲁迅 (1881-1936), who is widely considered to be the greatest Chinese writer, essayist and polemicist of the twentieth century. Writing as someone who was schooled in China in the early 2000s, ‘’Kong Yiji’ was a text that we all had to read and memorise in the ninth grade, the last year of China’s compulsory education. Set in a tavern in a fictional country town called Lu (modelled on Lu Xun’s hometown Shaoxing in the coastal Zhejiang province), Kong Yiji stands out among the tavern’s regulars for being the only customer who wears a scholar’s ‘long gown’ 长衫 (a symbol of his elite status) but who also drinks yellow rice wine standing up, something only poor manual labourers (the ‘short-coated class’ 短衣帮) would do. Throughout the story, Kong is mocked for his refusal to take off his dirty and tattered gown as well as for his sham morality — Kong maintains that stealing books doesn’t count as theft. He is also ridiculed for his useless learning — Kong knows how to write one character in four different ways and can recite passages from the Confucian Classics yet he was never able to pass the imperial examination and obtain stable employment. Pathetic as Kong Yiji might be, we were nonetheless taught in class that he was a victim of both the ‘oppressive feudal society’ and the imperial examination system that stifled individual creativity and perpetuated social inequality.

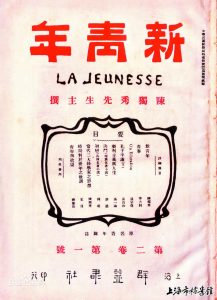

‘Kong Yiji’ debuted in the April issue of La Jeunesse 新青年 (New Youth) in 1919, a magazine created by Chen Duxiu 陈独秀, one of the founders of the Communist Party of China (CPC). The goal of the magazine was to enlighten and educate a new generation of youth fit to create and govern a modern, democratic China. Strangely, however, this laughable character from China’s despicable and inhuman past that Lu Xun and his compatriots so vehemently mocked and sought to overthrow, would resonate with millions of young Chinese today. Following that post, a new genre of internet writing arose under the hashtag #孔乙己文学# or ‘Kong Yiji Literature’, used by those who see their university education as a burden that prevents them from taking jobs seen as beneath their qualifications. ‘Had I not gone to university, I’d be content to work at a factory, tightening screws at an assembly line…but there’s no “ifs” in life…’ wrote one netizen. ‘When I first read the story of Kong Yiji as a child, I didn’t know its meaning. Now I realise that I am Kong Yiji!’ exclaimed another.

State media quickly attempted to change the new narrative around Kong Yiji which, to their eyes, was overly negative in its depiction of opportunities open to educated young people in China today. On March 17, China Central Television (CCTV) published an online commentary entitled ‘We must look seriously at the anxiety behind “Kong Yiji Literature”’. The commentary, while acknowledging the stress and competition young graduates face, stresses that ‘Kong Yiji’s tragedy lies not in the fact that he was educated, but in his refusal to take off the scholar’s gown and work hard towards improving his circumstances. The gown is not just a garment, but ‘a shackle around his heart’ 心头枷锁. The piece ends with the usual boost of ‘positive energy’ 正能量, solemnly declaring that ‘those with ambition will not remain trapped by their scholar’s gown’.

Two related news stories filled with even more ‘positive energy’ soon appeared on various state media: one of a 28-year-old graduate who quit her tedious white-collar job and who now earns over ten thousand yuan (roughly AUD 2000) a month by collecting and recycling scrap. The other story is about a couple, both college graduates, making over 9000 yuan in one night as street food venders.

Netizens were quick to question the validity of these stories. ‘Surely the 9000 yuan is their income not net profit’ someone asked. But it is the condescending tone of the CCTV commentary that caused emotions to run high. ‘So [you’re claiming] Lu Xun wrote the story to criticise Kong Yiji? Weren’t we taught that it was to criticise old China?’ one netizen retorted. ‘It was you who made me put on the scholar’s gown in the first place, now you are telling me to take it off?’ wrote another, referring to the fact that for years, the Party-State has actively promoted success stories of young students from impoverished backgrounds improving their circumstances by studying hard and getting into a good university.

Enraged by CCTV’s commentary, Guishange 鬼山哥 (literally ‘Ghost Mountain Brother’), a content creator and singer on China’s video sharing platform Bilibili wrote a sarcastic song entitled ‘Sunny, Happy Kong Yiji’ 阳光开朗孔乙己 in which he recasts Kong as a present-day patriot whose sanguine outlook is nonetheless a mask for his helplessness. As the modern-day Kong tells his audience in the tavern:

I keep my face clean, but my pockets are empty

So I put on my gown and scribe for the powerful ‘n’ wealthy

I thought work would be easy, but it’s 996

Working six days a week, twelve hours a day

When I had the nerve to ask for my pay, they called me malicious and the cops dragged my sad arse away

…

Optimism’s my armour, but tears flow behind this mask

I’m sunny, happy Kong Yiji; sunny, happy Kong Yiji [1]

The song attracted over three million views before the censors took it down just one day later, while suspending Guishange’s account. Posting on another platform, Zhihu, Guishange later said his only means of making money has been cut off, his savings were previously used up to pay for his mother’s hospital bills. He had been planning to earn some money as delivery driver, but his car broke down. ‘They’ve forced me into a dead end, and for what? Just because I told the truth?’ he asked.

Nearly a century ago, Lu Xun had already observed that ‘When the Chinese suspect someone of being a potential troublemaker, they always resort to one of the two methods, they crush him, or they hoist him on a pedestal’.[2] The irony, of course, as pointed out by the eminent Sinologist Pierre Ryckmans (aka Simon Leys), is that Lu Xun himself was subjected to both treatments: ‘when he was alive, the Communist commissars bullied him; once he was dead, they worshipped him as their holiest cultural icon.’ [3]

An even greater irony is the rich afterlife that Lu Xun’s writing continues to enjoy — now through multiple medias — for a writer, who when he was alive, was constantly tormented by suspicion toward the act of writing. In fact, Lu Xun’s dying words to his son were ‘Don’t ever become a pseudo writer or artist’.

The fact that ‘Kong Yiji’ is still widely discussed and debated more than a century after it was originally written can be seen as a vindication of Lu Xun’s penetrating insight and the unrelenting frankness with which he depicted the China of his day. It is also, ironically, the consequence of the CPC’s feverish canonisation of Lu Xun as their patron saint of literature. During the Cultural Revolution, Lu Xun was the only author other than Mao Zedong whose works were allowed to be read in public. The ubiquitous phrases ‘Chairman Mao has instructed us…’ and ‘Mr Lu Xun once said…’ were political slogans synonymous with continuous revolution and political correctness.[4] Even until recently, students in China had to study at least one text by Lu Xun per semester. Both the text and its prescribed meaning also had to be carefully memorised and subject to repeated testing.

Lu Xun has been so forcefully drilled into the consciousness of multiple generations that it is no surprise people would turn to him for every new ordeal they experience. After the military crackdown on student-led protests against corruption and for democracy and free expression around Tiananmen Square in 1989, many recalled Lu Xun’s remarks on the March 18 shooting of student protesters by Beijing security forces in 1926: ‘Lies written in ink can never disguise facts written in blood.’ During the hunger strike that was part of those protests, supporters hung a banner next to the young people refusing food and water painted with a famous line from Lu Xun’s short story ‘Diary of a Madman’: ‘Save the children!’

Lu Xun is thus the voice of both official and un-official China. During the COVID-19 pandemic, both state media applauding young volunteers trying to prevent rumours circulating about the virus as well as supporters of the ‘Blank Paper’ protests of late 2022 quoted the same message from Lu Xun to China’s future generation: ‘Ignore what the cynics have to say. Make your voice heard and your actions seen, like a firefly glowing in the darkness of night’.

Visitors at Lu Xun’s hometown in Shaoxing. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Unlike other writers of the ‘leftist canon’, Lu Xun never painted a future utopia in his writing, he was far too sober to indulge in any form of day-dreaming or to embrace any sect or ideology that made promises of a brighter future. He only wrote about the China he knew. At first, this was the China of his childhood, a small country town within a giant empire that’s crumbling into pieces, filled with pitiful characters like Kong Yiji and strange tales of ghosts and murders told by his nanny A-Chang. Later, it was the nominal republic plagued by civil unrest, tyranny, as well as a cultural and literary tradition that, in Lu Xun’s eyes, was not only irrelevant but thwarted China’s modernisation. A true iconoclast, Lu Xun went as far as calling for the eradication of the Chinese writing system, declaring that ‘If Chinese characters are not exterminated, there can be no doubt that China will perish.’

To make way for a better, modern China, Lu Xun was painfully aware that his own writing would be doomed along with the rest of the tradition he so long detested. ‘Let the awakened man burden himself with the weight of tradition and shoulder up the gate of darkness. Let him give unimpeded passage to the children so that they may rush to the bright, wide-opened spaces and lead happy lives henceforth as rational human beings’ Lu Xun wrote in 1919. [5] In this scenario, the gate of darkness eventually drops, crushing the weight-bearing hero into pieces. [6]

The self-effacing aspect of Lu Xun’s thought produced some of the most haunting and passionate images in his writing. For instance, there are the nihilistic flames that reoccur in his collection of prose-poems Wild Grass:

A subterranean fire is spreading, raging, underground. Once the molten lava leaks through the earth’s crust, it will consume all the wild grass and lofty trees, leaving nothing to decay….[7]

Then, there is the image of a self-devouring serpent in the same collection:

There is a wandering spirit which takes the form of a serpent with poisonous fangs. Instead of biting others, it bites itself, and so it perishes…[8]

Had he been alive today, Lu Xun would have been horrified to discover all the ‘museums, plaster busts, spin-off books, dedicated journals, plays, television adaptations, wine-brands’ operating in his name. He would have been even more shocked that young people still felt the need to evoke his work. After all, a China that clings to the culture and language of its past is a wushengde Zhongguo 无声的中国, a ‘voiceless China’, as Lu Xun famously told an audience at the Hong Kong YMCA in 1927. Though he was mainly speaking about the need to move away from classical Chinese, an outdated mode of expression permeated with Confucian authoritarianism; Lu Xun, who received a traditional Confucian education, saw himself as part of that decaying tradition when he urged the youth to ‘push aside the ancients, and express their authentic feelings’ so as to transform China from its state of ‘voicelessness’.

When asked about Lu Xun in 1990, the exiled Chinese writer Zha Jianying 查建英 had said: ‘The fact that he’s so relevant is very sad.’ More than thirty years later, Lu Xun remains sadly relevant. There is still a long way to go before Lu Xun can be allowed to rest in peace.

Notes

[1] Translation modified based on Alexander Boyd, ‘Censors delete viral “Kong Yiji Literature” anthem’, China Digital Times, 30 March 2023, online at: https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2023/03/censors-delete-viral-kong-yiji-literature-anthem/?ref=neican.org

[2] Simon Leys, The Burning Forest, London: Paladin, 1988, p.101.

[3] Simon Leys, The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays, Collingwood: Black Inc., 2011, p.258.

[4] Yu Hua, China in Ten Words 十個詞彙裡的中國, Taipei: Rye Field Publishing Co, 2010, p.100.

[5] Tsi-an Hsia, The Gate of Darkness: Studies on the Leftist Literary Movement in China, Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1968, pp.146-147.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Lu Hsun, Wild Grass, Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang trans., Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1974, p.3.

[8] Ibid, p.44.