Taiwan’s experience of 2021 was one of living with and then partially overcoming the anxiety over Joe Biden’s victory in the US presidential election of November 2020 — specifically whether that would diminish US support for Taiwan — as well as managing the Trumpist imprint on Taiwan’s domestic political discourse.

As the vote-counting for the American presidential election was under way on 4 November 2020, Taiwan’s ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) convened a meeting of its top-level decision-making organ, the Central Standing Committee, with President Tsai Ing-wen 蔡英文 presiding. Two Standing Committee members in attendance wore masks printed with the words ‘TRUMP: 2020 KEEP AMERICA GREAT’. President Tsai clarified during the meeting that Taiwan would respect the wishes of the American voters and her party had worked with and would continue to work with both political parties in the United States.1 She added that her government thanked both the Republican and the Democrat parties in the United States for what she stressed was their bipartisan support for strengthening US–Taiwan relations in recent years.2

But the symbolism was clear. A significant portion of Taiwanese society believes the increasing closeness of US–Taiwan relations over the preceding four years was due in large part to former president Donald Trump. For example, one of the Trump mask–wearing DPP Central Standing Committee members openly praised Trump as ‘the most pro-Taiwan US President in forty years’,3 while the general secretary (equivalent to caucus whip) of the DPP’s legislative caucus also euphemistically noted at the time that, should a different US administration come into power, he would need to observe closely whether the level of US support for Taiwan would remain as strong as during the Trump years.4

Their logic seems to be essentially ‘the adversary of my adversary is my friend’. In their eyes, despite Trump’s many inconsistencies and reversals regarding policy on the People’s Republic of China (PRC), his launching of the US–China trade war and various Trump administration officials’ frequent criticisms of the Communist Party of China (CPC) were convincing evidence that Trump, more than any American president in recent memory, was Taiwan’s friend.

The transition from the Trump administration to the Biden administration affected Taiwan on two levels: domestic and international. Domestically, Taiwan’s public sphere had moved towards a greater embrace of Trump-inspired conservative politics during the late Trump years. Its legacy contributed to political polarisation and increasing national ‘securitisation’ of domestic political processes, which continued even after Biden took power. Internationally, the faith in Trump combined with the end of his presidency led to heightened initial suspicion of the new US administration’s intentions towards Taiwan, leading to fear of strategic abandonment by the United States.

Taiwan ‘Hearts’ Trump

After the Trump administration launched the US–China trade war in 2018, the result was a downturn in the US–China relationship to an extent not seen in decades. For years, Beijing had been applying diplomatic and economic pressure on international institutions, multinational corporations, and other countries to deny Taiwan’s DPP government funding, recognition, and cooperation. Beijing scored such wins as excluding Taiwan from observer status in the World Health Assembly and the International Civil Aviation Organization after 2016, as well as persuading Nicaragua to switch official diplomatic relations from Taipei to Beijing at the end of 2021.

In contrast, Taiwanese society welcomed official visits by high-profile members of the Trump administration, including the Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar and Undersecretary of State Keith Krach. They also were pleased with then Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s last-minute press release (issued 11 days before he stepped down) on ‘lifting self-imposed restrictions on the US–Taiwan relationship’.5 They further pointed to the passage of important legislations, such as the Taiwan Travel Act (2018) and the Taiwan Allies International Protection and Enhancement Initiative (TAIPEI) Act (2019), as evidence of the Trump administration’s love for Taiwan — even though these were bipartisan acts by US Congress, not the Trump White House alone.

A significant portion of Taiwanese society therefore saw the Trump administration as a uniquely sympathetic partner, and many would have preferred Trump to have won a second term.6 A Global Views Monthly poll released in October 2020, for example, showed that 53 percent of Taiwanese believed a Trump election would be more beneficial to Taiwan’s interests, in contrast with only 16 percent for Biden.7

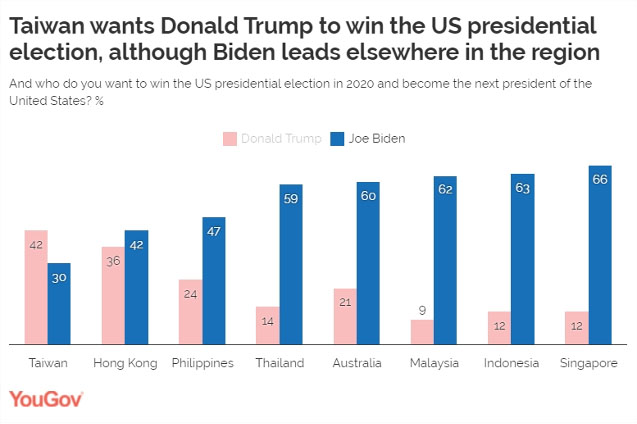

It follows that many Taiwanese people initially viewed Biden with suspicion and worry. A survey of public opinion in eight countries and regions in the Asia-Pacific in October 2020 (a month before the US election) by YouGov, a British internet-based market research and data analytics firm, revealed that only in Taiwan did more people want Donald Trump than Biden to win the US presidential election.8

In Taiwan, however, there was a significant difference in support for Trump between the two main parties. A Taiwanese Public Opinion Foundation poll in October 2020 showed that while 82 percent of the ruling DPP’s supporters preferred to see a Trump victory, only 19 percent of the supporters of the opposition Kuomintang (KMT) wanted to see Trump win.9

Polarisation in Taiwanese Public Discourse

Taiwan is divided into two primary political camps. One is the pan-Green coalition, which is led by the DPP and in recent years has favoured stronger alignment with the United States. The other is the pan-Blues coalition, led by the KMT, which tends to explore a more equidistant position between the United States and China. A strong Taiwanese affinity for the Trump administration continued to affect Taiwan’s domestic politics and international relations well into 2021.

Figure 1: A Taiwanese Public Opinion Foundation poll, October 2020 — ‘Who do people in Asia-Pacific want to win the US presidential election?’10

Source: YouGov.com

Before the Trump era, having undergone a relatively peaceful democratic transition in the 1980s and 1990s — which Taiwanese proudly called ‘the silent revolution’ 寧靜革命 — Taiwan generally enjoyed a relatively tolerant public sphere. Also, thanks to the continued pride Taiwan takes in its largely state-led economic modernisation (following what is sometimes called the ‘developmental state’ model), Taiwan previously did not have a strong instinctive antipathy towards left-of-centre ‘big-government’ policies.

Yet, domestically, support for Taiwan by the Trump administration and his Republican Party gradually created a receptive audience in Taiwan for political conservatism, especially of the conspiratorial and far-right variety. Numerous émigré mainland Chinese dissident writers became exceptionally popular right-wing commentators in Taiwan’s media.11 Collectively, they attempted to shift the ‘Overton window’ — the range of ideas perceived as acceptable and legitimate in political discourse — to the right.12 Often, they labelled anyone who was to the left of the hard right as unwitting ‘useful fools’ or ‘stooges’ of hostile authoritarian actors, or as consciously treacherous, Freemasonic or ‘globalist capitalist cabal’ conspirators.

Accordingly, Taiwan’s social media landscape during this period saw the popularisation of derogatory terms such as zuojiao 左膠 (‘leftard’) and baizuo 白左 (‘white leftists’), as well as new coinages such as ‘Apple-owning leftard’ 果粉型左膠 (roughly similar in meaning to the term ‘champagne socialist’) — terms that, ironically, are also popular among the nationalist ‘wolf warriors’ crowd in Beijing. The emerging use of such new politically loaded labels and the vilification of different opinions thus threatened to reduce the space for civility and tolerance of honest disagreement.13

This trend is having a deleterious effect on Taiwan’s public sphere and the quality of its political rhetoric. Taiwan’s ruling party, the DPP, historically represents two political traditions: political liberalism and Taiwanese nationalism. So, for example, in line with its liberal bent, in recent years, the DPP successfully promoted the legalisation of same-sex marriage and, in line with its Taiwanese nationalist bent, has encouraged a more assertive, Taiwan-centric national imagination — advocating, for example, for the public-school curriculum to dedicate more time to local Taiwanese history and languages.

The embrace of Trumpist discourse appears to have weakened the rhetorical purchase of political liberalism, thus leaving Taiwanese nationalism as the path of least resistance when the DPP picks its tool for political mobilisation. Taiwan’s latest plebiscites illustrated this phenomenon.

Direct Referendums and Partisan Politics

Taiwan held its seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth referendums on 18 December 2021. The four propositions were restarting Taiwan’s fourth nuclear power plant, banning imports of US pork containing ractopamine, requiring future referendums to be held on the same day as general elections if within six months of election day, and protecting the Datan Algal Reef off Taiwan’s north-western coast by stopping the construction of a proposed liquefied natural gas terminal in the vicinity.

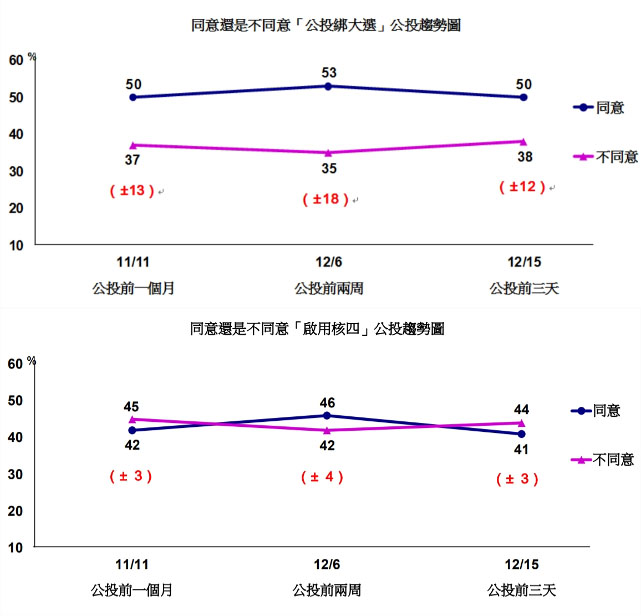

Figure 2: Results from Taiwan’s TVBS opinion survey: The topic with the highest support (top graph) was the timing of future referendums — almost 10 points higher than the topic with the lowest support (bottom graph), which was restarting the fourth nuclear power plant15

Source: TVBS

A popular opinion survey by Taiwan’s TVBS,14 conducted three days before the referendums, showed a wide range of views on the above topics. The topic with the highest support (50 percent for ‘yes’, 38 percent for ‘no’) was the timing of future referendums — almost 10 points higher than the topic with the lowest support, which was restarting the fourth nuclear power plant (41 percent ‘yes’, 44 percent ‘no’).

Yet, when votes were cast, all four propositions were rejected. Moreover, the results showed virtually identical support for the four topics, with the most popular proposition (combining future referendums with elections, which received a 48.96 percent ‘yes’ vote) separated from the least popular (restarting the fourth nuclear power plant; 47.16 percent ‘yes’) by barely 1.8 percent.

Preferences shown in the opinion poll failed to reflect the results because the voters ultimately cast their ballots less according to their own nuanced policy preferences and more according to the positions advocated by the party they supported.

Both major political parties in Taiwan, the DPP and the KMT, urged their voters to conduct the referendum equivalent of ‘straight-ticket voting’ — that is, to vote either ‘yes’ to all propositions (KMT) or ‘no’ to all (DPP). In the end, only 41 percent of the electorate voted. It was the lowest turnout for a referendum since 2008, and significantly lower than any other Taiwan-wide ballot (elections as well as referendums) in memory — with the sole exception of the 2005 National Assembly election, which was the first to introduce ‘party lists’, meaning electors voted for political parties rather than individual candidates.

The lower turnout meant, rather than a representative expression of the whole society’s policy preference, the ballot results disproportionately represented the diehard party faithful on both sides who bothered to show up to vote. The referendums ceased to be an opportunity to gauge public sentiment on specific policies and inform policymaking. Rather, they became a way to test the two leading political parties’ mobilisation strength — to see which side was better at ‘rocking the vote’.

During the referendum campaign, the KMT adopted a ‘scorched-earth’ position, calling on its supporters to vote ‘yes’ on all four propositions as a vote of ‘no confidence’ in the ruling DPP. The KMT’s slogan was ‘Cast four Yes votes; make Taiwan more beautiful’ 四個都同意, 台灣更美麗.

The ruling DPP meanwhile called on its supporters to vote ‘four Nos’. President Tsai Ing-wen’s official Facebook page issued numerous posts calling on ‘Team Taiwan’ to ‘step up’ 台灣隊站出來 and ‘cast four No votes; make Taiwan stronger’ 四個不同意, 台灣更有力. Treating the ballots as a battle, she asked supporters to ‘defend the referendum, defend the by-elections, and hold the line of defence for Taiwan’ 守住公投, 守住補選, 為台灣守住防線.

The significance of this is twofold. First, as a relatively new liberal democracy that only fully emerged from the shadows of authoritarianism in the mid 1990s, Taiwan is a great but unfinished democratic experiment. It has a plethora of newly available democratic tools at its disposal and a vibrant civil society bursting with long-repressed political passions. Instruments of direct democracy such as referendums are best used as an occasional corrective to major policy injustices or to allow the expression of fundamental value preference on questions that political elites are not best placed to answer. Yet, in Taiwan, they can take the shape of pitched, partisan battlegrounds.

The plebiscite, although an instrument of direct democracy, often becomes an extension of indirect democracy (party politics). Not only have Taiwan’s referendums often been intricately tied to party agendas, but also recall elections have become increasingly commonplace. Between January 2020 and January 2022, there were 14 recall elections.

Ideally, recall elections are triggered only when elected officials are so egregiously malicious or incompetent that for the health of the polity their removal cannot wait until the next election.

Yet, in 2016, changes in the law significantly lowered the turnout requirement for recall elections. To recall an official only required that there be more ‘yes’ (recall) votes than ‘no’ votes, and that the number of ‘yes’ votes must represent more than 25 percent of eligible voters. In addition, the legislative change lowered the ‘trigger condition’ for recall elections; they now require signatures from only 10 percent of eligible voters in the politician’s electoral district.

This lower threshold for recall elections, coupled with escalating political polarisation, has incentivised political parties and their affiliates to increasingly leverage recall elections as a low-cost way to reverse their losses in elections (by removing incumbent officials early in their tenure and triggering rematches). At minimum, recall elections can generate unfavourable publicity to weaken political opponents. Either way, the supercharged frequency of elections undermines those targets’ mandate to govern, while keeping the Taiwanese airwaves and society constantly in a ‘campaign mindset’. This can potentially distract everyone — parties, the media, and the electorate — from substantive policy discussions.16

Rise of National Security Concerns

Rising political polarisation may also be a consequence of increasing anxiety about national security. There has been a resulting tendency to ‘securitise politics’ and, increasingly, to use national security metaphors in political rhetoric. An example of the latter is, as aforementioned, during the latest referendum the DPP referring to itself and its supporters as ‘Team Taiwan’ and calling on its supporters to defend and ‘hold the line on behalf of Taiwan’ 為台灣守住防線. Although all those on both sides of the referendum were Taiwanese, the use of ‘Team Taiwan’ implied that those who opposed the DPP’s position must therefore not be on ‘Team Taiwan’.

This concerning trend highlights how the growing prominence of the ‘Taiwan issue’ has taken a toll on Taiwan’s domestic politics. If the perception of the growing Chinese military pressure against Taiwan has drawn greater international concern for and engagement with Taiwan, it has also fuelled domestic political dynamics in Taiwan that place a premium on ‘rallying around the flag’.

The emphasis on security justifies a narrative that all available resources must be mustered to strengthen the state so it can defend Taiwan against an existential military threat. Viewing Taiwan’s situation solely or predominantly through this lens, however, can blur the boundary between domestic and international issues. An unfortunate corollary is that any domestic political position at odds with that of the incumbent government may be framed as diminishing the state’s capacity to provide that protection. Thus, the line between ‘constructive criticism of the government’ and ‘weakening the government’s ability to provide for Taiwan’s security’ sometimes blurs.

The heavy shadow this national security discourse casts over Taiwan’s domestic politics, however, comes not only from the increased Chinese military pressure in the Taiwan Strait and the perceived effects on Taiwan of US–China strategic competition (see Forum, ‘Taiwan and the War of Wills, pp.203–207), but also from another Trumpian legacy: anxiety about how dependable a friend the Biden administration will be to Taiwan.

‘Beijing Joe’ and Managing Taiwan’s Abandonment Complex

The sense of camaraderie felt by many DPP supporters and others in Taiwan towards the Trump administration, who they saw as tough-on-China and unprecedentedly friendly towards Taiwan, meant they initially greeted Biden’s election with apprehension.

That sense of unease persisted in spite of the DPP government’s attempts at ‘firefighting’. For example, President Tsai swiftly congratulated Biden on his win in November 2020. As early as 8 November, she retweeted the message Biden had sent her when she won her second term in office, in which he had praised Taiwan’s ‘free and open society’ and said the United States should continue ‘strengthening our ties with Taiwan and other like-minded democracies’.17 Two days after the US Congress certified Biden’s victory on 6 January 2021, Tsai’s spokesperson, Xavier Chang 張惇涵, extended President Tsai’s best wishes to both the president-elect and vice-president-elect Kamala Harris, saying she looked forward to continued strengthening of the bilateral relationship.18

Yet many commentators in the Taiwanese public sphere, in the mainstream media and on social media alike still appeared to have bought into the narrative that since Trump was ‘tough on China’, whoever was ‘tough on Trump’ (Joe Biden) must therefore be ‘soft on China’ and possibly even eager to ‘sell out Taiwan’ 賣台 if the price was right.19 That kind of thinking continued to reverberate in Taiwan through 2021.

Ironically, both the pan-Green and the pan-Blue camps shared the apprehension about the transition to the Biden administration, though there were differences in detail.

The pan-Greens media generally distrust Biden as ‘the anti-Trump’. They are concerned about the influence of so-called leftist ideas on the Democratic Party — for example, the concern for climate change as represented by the slogan ‘Green New Deal’. They worry that to elicit cooperation from the PRC on climate, the United States will sell out Taiwan or otherwise marginalise its importance more generally. This sentiment is also powered in part by the aforementioned rise of anti-left-of-centre domestic discourse. Second, the pan-Greens are concerned by the Democratic Party’ close focus on the Russian threat (as embodied in their repeated concerns about alleged Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election, the Steele dossier, the Robert Mueller investigation, and so on). Some segments of the DPP worry that, unlike Trump, the Democrats will see Russia as a greater foreign and security policy threat to the United States than China. They imagined the United States under a Democratic president would return to a policy of benign neglect of Taiwan.

For the pan-Blues, a fundamental inclination to seek cooperation with China inclines them also to predict that the United States will sell out Taiwan to seek accommodation with Beijing, according to the logic of the ‘US–China grand bargain’ and ‘Finlandisation.’ The fact that such arguments still grace the pages of important American publications such as Foreign Affairs magazine and The New York Times has not helped.20 Alternatively, some pan-Blue–leaning commentators believe the United States under Biden will seek rapprochement with Russia. Following a US–China–Russia ‘strategic triangle’ analytical framework, they predict the United States will want to gang up with Russia to gain a two-against-one advantage against China. When the US does engage an ideologically alien Russia out of strategic convenience as predicted, the United States’ ‘values-based diplomacy’ will be exposed as but empty rhetoric. Therefore, Taiwan cannot count on US support based on shared liberal-democratic values.21 According to this logic, should Beijing initiate a cross-Strait war, the United States could not be relied on to come to Taiwan’s aid, so Taiwan had better find ways to placate Beijing and turn down the heat in the relationship before the cross-Strait tension reaches a crisis point. Therefore, some pan-Blues believe, to proactively pursue its own interests and protect itself from potential betrayal by the United States, Taipei needs to seek rapprochement with Beijing.

Conclusion

Many Taiwanese on both sides of the political spectrum were apprehensive at first about whether they could trust the Biden administration. American officials appeared at different moments to reassure Taipei that they would not abandon the island, but they stopped short of overtly changing the United States’ long-standing posture of ‘strategic ambiguity’ on Taiwan.22

In 2021, Taiwan paradoxically experienced both rising international visibility and heightened fear of strategic abandonment. In 2021, joint statements issued by the leaders of the G7 summit, the United States–European Union high-level consultation, and several other prominent international groupings all expressed interest in peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait. For some countries, it was the first time they had directly expressed a stake in Taiwan’s peace and stability in such a prominent international setting. Yet, despite this increase in international support, for many Taiwanese, 2021 was a painful journey of overcoming their anxiety about the Biden administration’s commitment to Taiwan and managing their recurring fear of abandonment.