Shangri-la

Source: Yota Takaira, Flickr

IN THE LATTER PART OF 2018, China’s State President and Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping 习近平 made a series of widely reported public statements about Party support for the private sector. He appeared on television in an interview alongside Politburo member, Vice-Premier Liu He 刘鹤 — a key architect of China’s current set of economic and financial policies — and convened what Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post described as an ‘unprecedented forum’ to hear the views of business representatives. The Party, Xi reassured his audience, placed equal importance on private enterprises and state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

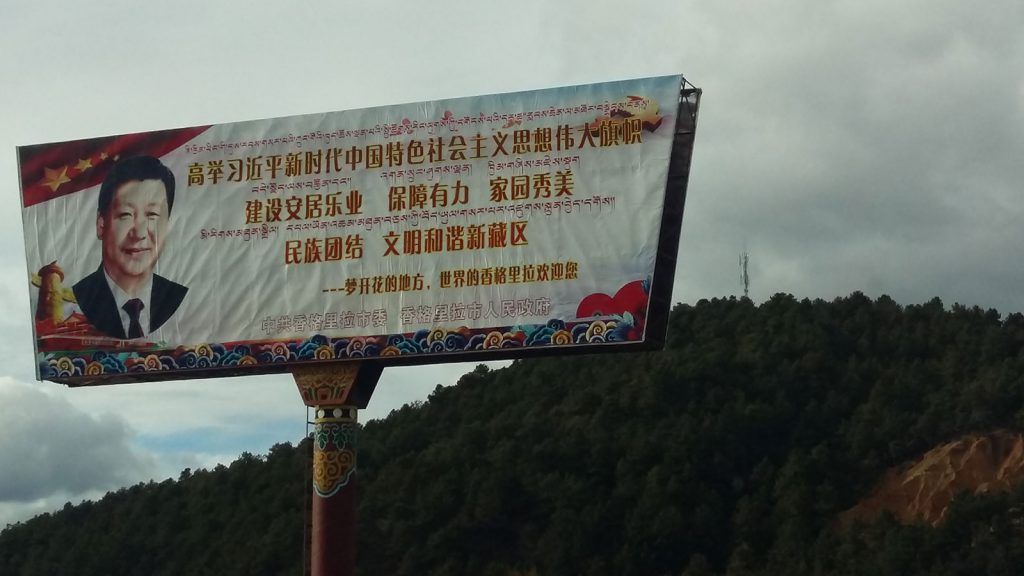

A billboard extols the virtues of Great Leader Xi Jinping’s Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era

Image: Ben Hillman

State media called Xi’s media blitz an ‘anti-anxiety pill’, an antidote to a growing sense of unease among China’s business community about the rapid expansion of SOEs at the expense of the private sector. An online essay published by former investment banker Wu Xiaoping 吴小平 in September 2018 had added to entrepreneurs’ alarm by suggesting that having helped advance China’s economy, the private sector should now fade away. Even though online commentators poured ridicule on the essay, the viral attention it received was a reminder that in China, where the state wields much of its power through direct control of economic activity, private enterprise can still feel ideologically vulnerable. Anti-private business sentiment has been on the rise in recent years, not only on the fringe of policy debate, but also in the corridors of power. A growing chorus of leftist intellectuals have called time on private business. Earlier in the year, Zhou Xincheng 周新城 — a professor of Marxism at the Renmin University of China — wrote in the Party theoretical journal Qizhi 旗帜 that ‘Communists can sum up their theory in one sentence — eliminate private ownership’.

In 2018, China celebrated the fortieth anniversary of economic reform and an ‘open door’ to the outside world 改革开放 — the policy shift that began turning the country from an impoverished economic backwater into the global economic powerhouse that it is today. Central to the economic reforms was the enabling of private enterprise. One of the first reforms was to allow farmers to sell surplus produce on the open market. Village and collective enterprises soon emerged and larger industrial corporations eventually followed. Private enterprise has become an increasingly important part of China’s growth story for the past forty years, contributing to an estimated sixty per cent of GDP growth and generating ninety per cent of new jobs in 2017. According to CCP ideology, however, a successful private sector is not the endgame for economic policy, but a stage in the country’s progress toward communism. Party theorists under Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 justified the economic reforms by arguing that China was at an early stage of socialism and needed to adopt market policies to boost economic growth before a more egalitarian socialist society could be created — a theory that became known as Socialism with Chinese Characteristics 中国特色社会主义.

Since coming to power, Xi Jinping has reaffirmed the centrality of Party ideology, rebranding it Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era 新时代中国特色社会主义. Some of the elements of Xi’s New Era are already apparent. Politically, China has become more authoritarian. Xi has overseen a strengthening of the Party and the state apparatus through which he and the Party wield power. Political opponents and dissenters have received harsh treatment. Obedience is demanded of civil society and academia. As many as a million Uyghurs and Turkic Muslims have been incarcerated in ‘re-education’ camps to purge them of loyalties and values external to official ideology. (See Chapter 4 ‘Internment and Indoctrination — Xi’s “New Era” in Xinjiang’.) In the economic realm, Xi’s policies have strengthened state control of the economy by empowering SOEs, which has diminished the value of private firms — a phenomenon popularly expressed as ‘the state advances, and the private sector retreats’ 国进民退. In 2018, private sector profits were down twenty-two per cent year on year — their biggest decline since 1978. By contrast, SOE profits were up seventeen per cent in the first ten months of the year. This development is a major reversal of the trend of the past three decades, during which time private firms’ return on assets has been consistently higher — as much as triple — than that of state-controlled firms.

‘What Good is Your Money?’

Shortly after Xi made his morale-boosting remarks, I met with local entrepreneurs in Yunnan, in south-west China. At a dinner with local businessmen, some of whom I had known for many years, Xi’s remarks were the subject of lively debate. My fellow diners agreed that conditions for the private sector, such as access to finance and government contracts, were the worst in living memory, and that this was a result of Xi’s preference for SOE-led economic growth. The diners did not agree, however, whether Xi’s more recent, reassuring remarks signalled a favourable policy shift.

‘The problem is that the Centre always says what you want to hear, but there’s a big gap between what they say and what they do’, remarked the owner of a small construction firm. ‘Yes, well at least they’re saying it’, said another. ‘So I guess the comments are progress of sorts.’ Others spoke of ongoing mistrust of business, quoting old sayings that disparage business such as ‘if it’s not crooked, it’s not business’ 无奸不商. They linked it to both Confucian values, which placed the merchant below everyone but soldiers in the social hierarchy as well as ideology, and the power differential in China’s politics-in-command economy. As one of them put it, ‘what good is your money if a low-level Party cadre can halt your activities with a stroke of a pen?’

SOE-led construction of a 180 km above-ground freeway between Shangri-la and Lijiang

Image: Ben Hillman

After years of special treatment for SOEs, it appears that China’s economic policy has reached the same critical juncture as in the early 1990s, when the Party lunged to the left in response to the crisis in 1989, after people took to the streets first to protest corruption and then to demand democracy and a free press before the army’s violent suppression of the movement. As the Party-state moved to assert control over the private social and economic activity that they perceived had led to the chaos, it took paramount leader Deng Xiaoping’s trip to the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in 1992 — a historic trip now popularly referred to as Deng’s Southern Tour 南巡 — to reassert the Party’s support for economic reform and an ‘open door’ to the outside world. A pro-business official at the table that night predicted that 2018, forty years after the start of the reform era, would be remembered as the year in which China’s leaders either confirmed their commitment to economic liberalisation or decided that state capitalism was their preferred path for economic development.

In the Yunnan locality where the dinner took place, the local economic situation was dire. Over the past two decades, tourism had taken over from mining as Yunnan’s main economic driver, allowing private enterprise to flourish and outpace the SOEs that had previously dominated the local economy. In Zhongdian — a county in Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture that changed its name to Shangri-la in 2001 — local authorities offered tax breaks and other concessions to tourism-related enterprises. One firm helped the county develop and promote a circuit of scenic spots, including a gorge along the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, a series of limestone terraces, and a turquoise-blue lake ringed by forest. At each site, the company managed visitor access, making improvements to paths and steps, and erecting ticket gates to collect entrance fees. In return for an agreed annual rent to the county government, the company collected and kept all the revenue from ticket sales.

Tourism began driving rapid economic growth in Yunnan province. Between 2006 and 2016 the value of the province’s hotel and catering industry increased by 600 per cent, from AU$1.6 billion to AU$9.6 billion. In Shangri-la, local entrepreneurs, sometimes in partnership with outside investors, built hotels and guesthouses in the town centre. Hundreds of townsfolk opened small shops and eateries. Others developed new products such as local herbal medicines and dried meats to sell to tourists. One local Tibetan man made a fast fortune by selling locally produced Tibetan knives; he proudly displayed his newfound wealth by driving the first Hummer to hit the county’s streets.

The county government established an SEZ along its southern border, close to the bigger and more prosperous city of Lijiang. Low taxes, cheap land, and abundant hydropower attracted new private enterprises, including a barley wine distillery and food processing plants. A growing number of tourists, and government expenditure kept the economy pumping.

As Beijing began investing more in regional infrastructure, opportunities for private business increased. Big construction firms moved in from outside the region, but local subcontractors sprung up, too. When I first visited Shangri-la in the early 2000s, one of the richest men in town was the Tibetan owner of a concrete factory who had not attended school past the fourth grade. The region’s private sector expanded rapidly during the 2000s, generating jobs that were often difficult to fill.10 (See my Forum ‘Shangri-la and the Curse of Xi Jinping’ in the China Story Yearbook 2017: Prosperity, for more details.) In the early days of tourism development, the best jobs were taken by Han Chinese, but opportunities eventually spread to ethnic Tibetans and other groups.

Cleaning Up

The private sector boom rolled on until Xi came to power in 2012. Xi’s anti-corruption campaign hit hard as extravagant local government spending, including on state-sponsored travel, was reigned in, and the local gift economy shrank. These developments, and a crackdown on dodgy tour operators in 2015, dealt a major blow to the local tourism industry. Yunnan had become notorious for cut-price holiday packages, which unscrupulous operators often sold below actual cost to unsuspecting tourists, in the expectation that profits would be recouped from commissions delivered by shopping centres selling souvenirs and local produce set up along highways for the specific purpose of syphoning cash from tour groups.

In Diqing, a lucrative way to extract cash from tourists was to sell them local herbal remedies such as the prized caterpillar fungus, literally worth more than its weight in gold. The scams here are similar to those in many other parts of China. As tourists are ushered into the roadside warehouses, a fake shopper known as a tuo 托 would appear, and, speaking in the group’s native dialect, exclaim the value and quality of the fungus being sold. The tuo would order a large quantity, the group’s guide might add that this was the best place to buy the prized herb, and the tuo would then encourage the shoppers to have the fungus ground into a powder for easier transport and preservation. During the grinding process, the shop assistant would substitute different, less valuable herbs. The local operators, including the guides, would then make their profits from shopping commissions and rip-offs.

Following an incognito trip to the province’s tourism hot spots in 2015, Yu Fan 余繁, the Yunnan Deputy Party Secretary responsible for tourism, recommended urgent action to clean up the travel business. The Provincial Governor, Ruan Chengfa 阮成发, issued an order to close all such souvenir warehouses. In the words of one travel guide I spoke to, provincial officials succeeded, ‘a little too well’. The rip-off joints were effectively shut down, but instead of changing their business models, they simply moved to the neighbouring provinces of Guanxi and Guizhou, where standards were as lax as they had previously been in Yunnan.

As visitor numbers declined, hotels and restaurants started going bust. Private owners of ticketed attractions sought to offload their assets. The only buyers were cash-flushed SOEs. The Yunnan Tourism Investment Company swooped on Shangri-la’s top attractions, including Tiger Leaping Gorge and the Snub-nosed Monkey Reserve in neighbouring Weixi County. Diqing’s regional tourism investment company purchased the Balegezong Gorge, a premier tourist attraction, only to on-sell it to the bigger investment company owned by Yunnan province itself. As one local businessman observed: ‘it’s like watching fish being eaten by bigger and bigger fish’.

The Big Fish

In the past few years of studying economic development in the south-west, I have observed the SOE juggernaut re-establish the state’s predominant position in the local economy. Energised by easy access to cheap capital and Xi Jinping’s pro-SOE policies, local or provincial-level investment companies, originally established to fund investment projects in line with Party policies, quickly expanded, setting up subsidiaries and buying up assets. In Diqing, the Yunnan Construction and Investment Holding Group, the City Construction Investment Company, the Yunnan Energy Investment Company, and the Yunnan Cultural Industries Investment Company all seem to have sprung up overnight, with their shiny new offices in the centre of Shangri-la’s expanding town. Within a few years, these SOEs have become major players in the regional economy.

As economic conditions worsened for private businesses, they turned to banks for loans, but were often refused — the SOEs having hoovered up local banks’ available capital. Under Xi, banks across China have tightened their lending standards — especially when it comes to private firms. As one ex-local banker told me,

These days, if you lend a businessman money and he defaults, you will be suspected of corruption and investigated. If you lend an SOE money and it can’t meet repayments, the leaders will arrange for countless extensions. If the SOE defaults it’s nothing more than an internal administrative problem. The bank won’t be blamed. So why would banks lend to private firms when SOEs are so hungry for capital?

Chinese banks typically require private firms to pay a deposit of equal value to the loan amount or provide collateral of up to four or five times the value of the loan. As in other parts of China, some firms use equity (stock) in their company as collateral, forfeiting ownership if they default. Through such defaults, SOEs across China have been able to buy private firms and their assets on the cheap.

One hotel owner I spoke to had mortgaged his house to secure a business loan, estimating his house to be worth more than double the loan amount. He was further required to demonstrate sufficient cash flow to meet scheduled repayments. Other local business owners were unable to meet such stringent bank requirements and were thus denied loans, forcing them to either sell up or turn to private money lenders. Private money lenders, often connected to organised crime, are ubiquitous in China. As my hotelier friend told me, ‘I can make a phone call today and get a bag of cash delivered tomorrow. It will cost me twenty to thirty per cent in interest. I don’t want to do this if I can avoid it. If I can’t make repayments I’d be in big trouble.’ In the past few years, as many as four Diqing business owners who were unable to repay debts, including a restaurateur I knew personally, committed suicide.

In response to the economic downturn, the central government has pulled the fiscal stimulus levers, providing grants for infrastructure and rural development. In Diqing, work began on a railway in 2014 and on a 200-kilometre above-ground freeway in 2017 (both scheduled for completion in 2020). But local entrepreneurs say that the fiscal stimulus provided little respite for the private sector because the benefits mostly went to SOEs. As one prefecture official explained, ‘SOEs are winning the contracts because the government thinks they are low risk. The contracts are subject to less scrutiny, and if something goes wrong it can be fixed politically. When government funds take time to arrive, the SOEs can borrow against the contracts and start work immediately.’ The Yunnan Construction and Investment Holding Group, founded only in 2016, now dwarfs other enterprises in Diqing. It holds the freeway and railway contracts, worth a combined total value of 100 billion yuan (AU$22 billion), and also spent a staggering 1.2 billion yuan (AU$250 million) to build the world’s largest stupa at the entrance to the town. In late 2018, the company began digging the foundations for an enormous expansion of Shangri-la’s old town centre, doubling the size of the recently constructed ‘old’ town.

There’s another reason for the rise of SOE-led development. Under Xi, the Party Organisation Bureau — the agency responsible for vetting and promoting key Party officials — has strengthened the practice of rotating officials between regions. This practice dates back to dynastic times, and was intended to inhibit graft by preventing officials from getting too close to the people in their jurisdiction; for this reason, too, mandarins were not allowed to serve in their home towns. Party secretaries used to be local residents. This is less likely these days. Local cadres are no longer so closely connected to the political and economic networks through which spoils might be shared. According to a former official at the local Department of Commerce, ‘rather than deal with local economic interests, outsider Party secretaries are more likely to bring in SOEs’.

Local entrepreneurs can still pick up subcontracting work from SOEs, but their profits were squeezed to such an extent that it is not worth it. And SOEs are expanding so rapidly they are moving into spheres of economic activity that had once been the exclusive domain of the private sector — for example, boutique hotels and resorts. Their resources and political connections have made SOEs formidable competitors. One hotelier told me he had been fined a large sum by the police because a staff member had made a mistake when entering a foreign guest’s passport number into the police-controlled online guest registration system. He maintained that no SOE-run hotel would have been subjected to such a fine.

Who Will Advance, and Who Will Retreat?

In the face of such pressures, some local businessmen have decided to retire, investing their money in stocks and mutual funds. In other parts of China, some entrepreneurs would prefer to invest abroad, but capital controls have made this difficult.

‘By far the best option for many businesspeople is to sell to an SOE or enter into a partnership with an SOE’, my local government informant asserted. When I asked him about Xi’s pro-business reassurances, he said, ‘it is going to take much more than promises’. He suggested that local governments, banks, and SOEs would need to change their behaviour, with local Party bosses made responsible for the survival of the private sector. ‘Over the next twelve months, we will see whether the Party intends to reverse the policy of “the state advances, and the private sector retreats”.’

I reminded him of his earlier remark about the Party having come to a crossroads similar to that it faced in 1992 when Deng embarked on his Southern Tour. Perhaps Xi might similarly choose the path of liberalisation. ‘I don’t think so,’ he responded. ‘The SOEs have become a very powerful tool for the Party. But in China you never know what will happen.’

Notes

‘Xi’s reassurances to private sector are step in right direction’, South China Morning Post, 3 November 2018, online at: https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/2171556/xis-reassurances-private-sector-are-step-right-direction

‘A Chinese writer calls for private companies to fade away’, The Economist, 6 October 2018, online at: https://www.economist.com/china/2018/10/06/a-chinese-writer-calls-for-private-companies-to-fade-away

Xie Wenting, ‘Reform and opening-up a consensus in China despite occasional extreme views’, Global Times, 13 February 2018, online at: http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1089530.shtml

‘China’s private sector contributes greatly to economic growth: Federation Lleader’, Xinhuanet, 6 March 2018, online at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-03/06/c_137020127.htm

Ben Hillman, ‘Xinjiang and the Chinese Dream’, East Asia Forum, 24 October 2018, online at: http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/10/24/xinjiang-and-the-chinese-dream/

Chinese Ministry of Finance cited in, ‘China’s SOE profits keep steady growth in Jan- Oct’, Xinhuanet, 27 November 2018, online at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-11/27/c_137635149.htm

Nicolas Lardy, ‘The Changing Role of the Private Sector in China’, Reserve Bank of Australia Conference Volume 2016, pp.37–50.

On the development of tourism in the region see Ben Hillman, ‘Paradise under construction: Minorities, myths and modernity in northwest Yunnan,’ Asian Ethnicity, vol.4, no.2 (June 2003): 177–190.

Ben Hillman and Lee-Anne Henfry, ‘Macho minority: Masculinity and ethnicity on the edge of Tibet,’ Modern China, 32, April (2006): 251–272.

Ben Hillman, ‘Monastic politics and the local state in China: Authority and autonomy in an ethnically Tibetan prefecture’, The China Journal, 54, (July 2005): 29–51.

‘China GDP: By Income: Yunnan’, CEIC Data, online at: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/china/gross-domestic-product-yunnan/gdp-by-income-yunnan

On the early challenges of tourism-led development, see Ben Hillman, ‘China’s nany Tibets’, Asian Ethnicity, vol.11, no.2 (June 2010): 269–277; and Ben Hillman, ‘The poor in paradise: Tourism development and rural poverty in China’s Shangri-la’, in X. Jianchu and S. Mikesell, eds. Landscapes of Diversity: Proceedings of the III Symposium on Montane Mainland South East Asia (MMSEA), Kunming: Yunnan Science and Technology Press, 2003.

For further information on the impact of economic development on different ethnic groups and ethnic relations, see Ben Hillman, ‘Ethnic tourism and ethnic politics in Tibetan China’, Harvard Asia Pacific Review, (January 2009): 1–6; and Ben Hillman, ‘Unrest in Tibet and the limits of regional autonomy’, in Ben Hillman and Gray Tuttle, eds. Ethnic Protest and Conflict in Tibet and Xinjiang, New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.

On the excesses of local officialdom, see Ben Hillman, ‘Factions and spoils: Examining local state behavior in China,’ The China Journal, vol.62 (July 2010): 1-18; and Ben Hillman, Patronage and Power: Local State Networks and Party-State Resilience in Rural China, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014. On the impact of Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign on the region see, Ben Hillman, ‘Shangri-la and the curse of Xi Jinping’, China Story Yearbook 2017: Prosperity, Canberra: ANU Press, 2017.

For more detail on the drivers and impacts of urban construction, see Ben Hillman, ‘The causes and consequences of rapid urbanisation in an ethnically diverse region’, China Perspectives, no.3 (September 2013): 25–32; and Ben Hillman, ‘Shangri-la: Rebuilding a myth’, 16 November 2015.