Forum: The Environment — Control and Punishment

Iron-Fisted Punishments

by Siodhbhra Parkin

In 2016, the Chinese government struggled to build credibility in its capacity to handle serious environmental issues both at home and abroad. The past two years have seen a flurry of new laws, plans, and agreements passed with great fanfare by the government to address China’s severe and growing pollution levels. However, the new enforcement mechanisms established by these policies have lacked immediately discernible impact. Instead, the signing of the Paris Agreement and promulgation of the most environmentally friendly Five-Year Plan notwithstanding, China experienced new, high-profile environmental disasters that clouded an already troubled legacy.

Cracking Down on Water Management

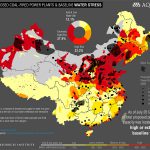

by Wuqiriletu

On 11 April 2016, a reporter for the National Business Daily 每日经济新闻 named Zhang Wen 张雯 wrote a worrying report titled ‘Ministry of Water Resources thoroughly investigates groundwater resources: eighty percent is not suitable for drinking’. According to statistics published by the Ministry of Land and Resources, more than 400 cities out of 657 nationwide are using groundwater for drinking water. That means seventy percent of the population is drinking groundwater, of which eighty percent is not suitable for drinking.6 However, soon after the report’s publication, Chen Mingzhong 陈明忠, Department Head of the Water Resource Division of the Ministry of Water Resources, responded that the reporter had misread the data. He said that, in fact, people in 1,817 out of 4,748 cities and towns are drinking groundwater with a water quality compliance rate of about eighty-five percent.7 One thing is certain, however: China is in a state of ‘water stress’, and one of the difficulties in the search for solutions to this pressing problem is that the available official data is often contradictory.

A Glimmer of Hope

by Jane Golley

In my Chapter ‘Under the Dome’ in the China Story Yearbook 2015, there was plenty of cause for pessimism surrounding China’s quest for low-carbon, green growth. While the news is not all good for 2016 (see Forums ‘Environmental Disasters’, pp.21–23 and ‘Iron-Fisted Punishments’, pp.25–27), there have been some positive environmental outcomes for China and the world as well. Domestically, the release of the Thirteenth Five-Year Plan in March 2016 strengthened China’s commitment to developing a low-carbon green economy (see Chapter 1 ‘What’s the Plan?, pp.xxvi–15). There is ample evidence to suggest that this commitment is real. In May 2016, Greenpeace declared that ‘China’s Thirteenth Five-Year Plan is quite possibly the most important document in the world in setting the pace of acting on climate change’. Greenpeace further noted that ‘2020 energy targets that would have seemed quite meaningful or even ambitious a few years ago have now become redundant’.12 Of the many figures they provide to support their positive assessment is the share of coal in China’s total energy mix, which is expected to fall below sixty-three percent in 2016 — a one-percentage-point annual drop since 2010, and only one percentage point above the target of sixty-two percent for 2020.