A central tenet of China’s foreign policy under Xi Jinping, according to his speeches, is improving relations with its neighbours. China has fourteen land neighbours: more than any other country, and with some — India, Vietnam, and Russia for example — their history is complicated. Others, particularly North Korea, pose direct and complex challenges. Its maritime neighbours, meanwhile, include Japan, the Republic of Korea, and the Philippines — US allies with which China has tricky relationships. If Xi Jinping is to achieve his stated goal of turning China into a ‘moderately prosperous society’, and maintaining Communist Party rule, a benign external environment will support domestic progress. But claims of a ‘peaceful foreign policy’ and pursuing better relations with its neighbours sit awkwardly with some of China’s other policies, such as that of building islands on land features claimed by other countries, and even on their continental shelves.

Who Rules the Waves?

On 12 July, a tribunal convened under article VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) ruled against China in its dispute with the Philippines over some land features in the South China Sea. This coincided with Rodrigo Duterte — the ‘Filipino Trump’ — taking power in Manila. The ruling looked like a momentous development in this seemingly intractable matter, but also led a strategic pause in Asian diplomacy, as China proved its skill at damage control through very proactive diplomacy, and claimant countries waited to see what US action might ensue.

As with other territorial disputes in Asia, the South China Sea dispute has a very long history. The current uncertainty about ownership stems partly from the 1951 San Francisco accords, which obliged Japan to renounce its claims to the Spratly Islands 南沙群岛 and other conquered islands and territories — but didn’t spell out who would then have sovereignty over them. China asserts sovereignty over every land feature within its ‘Nine-Dash Line’, which is ambiguous but essentially covers all the land features in the South China Sea. There are five other claimant countries.

In an attempt to clarify matters in its own favour, the Philippines had filed fifteen submissions to the arbitral tribunal in January 2013. In July 2016, the court declined to rule on seven of these, and asked for clarification on one. It ruled in favour of the Philippines on the remaining seven. The ruling was damning for China on all counts, even if the result has made no difference to the situation on the water: China did not retreat from its claims, either rhetorically or physically.

Beijing insists that the dispute in the South China Sea is about sovereignty, and as such should be resolved through bilateral negotiations between the countries concerned. Since China has also said it can never compromise on sovereignty, it is not clear what it hopes to achieve. Despite Chinese accusations to the contrary, the tribunal did not rule on matters of sovereignty, which are outside the remit of the UNCLOS. In fact, it explicitly declared that it would not ‘rule on any question of sovereignty over land territory and would not delimit any maritime boundary between the Parties’. Rather, it had looked at the issues over which it formally had jurisdiction, including the legal basis for the Nine-Dash Line (see the China Story Yearbook 2015: Pollution, Chapter 6 ‘Belt Tightening’). It considered the status of the various land features of the Spratlys to resolve the crucial question of whether any of these features could be considered an island (capable of sustaining habitation in its natural state), and therefore entitled not only to twelve nautical miles of territorial waters, but also to a two-hundred-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

The five judges argued that there was no basis in law for the Nine-Dash Line. They concluded that the largest feature of the Spratly islands — ‘Itu Aba’ or ‘Taiping Island’, which is currently controlled by Taiwan — was not actually an island. (See Information Window, ‘Taiwan and the South China Sea’) This implied that none of the other features of the archipelago were islands either. The judges ruled that any valid ‘historical rights’ — China’s key argument for sovereignty — had been taken into consideration by UNCLOS at the time of drafting, leaving no possibility for a legal argument based on abstract ‘historical rights’. The tribunal also found that China had infringed upon the rights of Filipino fishermen to fish around the Scarborough Shoal, and had caused massive environmental damage to the Philippines’ continental shelf through overfishing of certain species.

China had consistently refused to accept that the tribunal had any authority to adjudicate the matter. It argued, without evidence, that the tribunal was covertly ruling on sovereignty, an issue the parties had agreed to resolve through friendly negotiation. The Chinese government referred to the tribunal as ‘political provocation under a cloak of law’, though it did offer some national positions in the form of diplomatic notes.

Throughout the proceedings, China called the credentials of the arbitral judges into question in commentary across state media and official statements. China had refused to appoint its own judge even though it had the right to do so. The Philippines, therefore, requested the President of the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), Shunji Yanai, to appoint one on their behalf. Xinhua, in a news analysis titled ‘Shunji Yanai, manipulator behind illegal South China Sea arbitration’, calls the ITLOS President ‘rightist, hawkish, close to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, pro-American, unfriendly to China’. Vice Foreign Minister Liu Zhenmin 刘振民 also complained that none of the judges were Asian, and, therefore, could not possibly understand the situation, speculating that they were probably only motivated by Filipino money. Diplomats and scholars from the People’s Republic also claimed, without basis, that the tribunal exaggerated its association with the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) and ITLOS. In reality, it was convened under article VII of UNCLOS using the administrative services of The Hague PCA, in the same format used for most maritime dispute resolutions, and was the only legal option available to the Philippines in this case. That various media used the shorthand ‘PCA tribunal’ was not the fault of the judges.

China’s maritime claim (red) and UNCLOS’ Exclusive Economic Zones (blue) in the South China Sea

Source: Wikimedia Commons

China had strongly pursued its claim to the South China Sea islands through the year, leading critics to accuse Beijing of wanting to create a ‘Chinese Lake’, controlling all the waters within their Nine-Dash Line, and, thereby, all navigation through the area. This would constitute a clear challenge to the US and other countries’ concepts of their own navigational rights in the area and, by extension, national interest.

And yet, China’s approach has seemingly proved effective. It has successfully constructed over thirteen square kilometres of land on the seven features it controls in the Spratly Islands, according to the Pentagon’s 2016 report on China’s military. This is around ninety-five percent of the total land reclamation in the area. China had announced in June 2015 that the construction phase was over. This appears to be the case. Instead, 2016 saw installation of facilities including airstrips, aircraft hangars, radar and missile systems, and lighthouses. The longest airstrip, on Subi Reef (渚碧岛) is 3,250m long, much more substantial than the airstrips operated by the other claimant countries, and theoretically capable of landing a Boeing 747. It can handle any plane of the People’s Liberation Army Air Force fleet. Hainan Airlines conducted a civilian test flight landing on Subi Reef on 13 July, the day after the tribunal ruling.

An airstrip and aircraft hangar on Mischief Reef, from the CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, captured on 21 July 2016

Source: amti.csis.org

In January, Vietnamese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Le Hai Binh accused China of violating Vietnamese sovereignty by landing a plane on Fiery Cross Reef, a land feature of the Spratlys that is also claimed by Taiwan and the Philippines. China asserted its sovereign right to make the test flight on the new airstrip, and followed up with further test flights.

Sporadic ‘freedom of navigation operations’ during the year by the US, supporting former President Obama’s assertion at the US–ASEAN Summit in February that ‘the United States will continue to fly, sail and operate wherever international law allows’, did not seem to affect China’s behaviour. Press reports in July indicated that, when he met Xi Jinping in Washington in March, Obama had put further pressure on the Chinese president to rein in China’s construction activities in the South China Sea. This followed US intelligence reports that suggested China was preparing to reclaim land on Scarborough Shoal (claimed by China, Taiwan, and the Philippines). Some US commentators claimed that the conversation between Obama and Xi led to China’s decision to avoid further, overt provocation in a year when a high priority was the successful hosting of the G20 Summit in Hangzhou. The decision-making process in Beijing is too opaque to know whether the conversation with Obama did, in fact, lead to a change in plans. Certainly, Chinese leaders would never publicly admit conceding to pressure from a US president. Nonetheless, although the Philippines reported the presence of dredging ships around the Scarborough Shoal in September 2016, no building seems to have taken place there.

ASEAN continued to demonstrate its powerlessness following the ruling. At the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ meeting in late July in Vientiane, Cambodia successfully prevented the group from making a strong statement on the tribunal outcome. Cambodia — not a claimant, but a beneficiary of Chinese largesse — had previously orchestrated ASEAN’s first ever failure to issue a summit statement in 2012, also over language on the South China Sea.

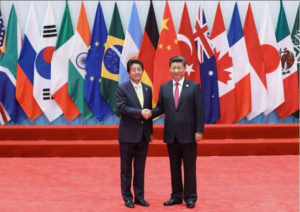

Obama and Xi greet each other at the G20 Summit in Hangzhou

Source: Official White House, photo by Pete Souza

Codes of Conduct

In 2002, China was a signatory, along with the member states of ASEAN, to a ‘Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea’, which aimed to create the conditions for ‘a peaceful and durable solution of differences and disputes’ between them, but which China and other claimants have since seriously violated. Following the tribunal ruling in July, China announced a diplomatic push to achieve progress on the 2002 proposal for a binding code of conduct in the South China Sea. Beijing called a senior officials’ meeting for August 2016 in Inner Mongolia. The meeting boasted of ‘several breakthroughs’ including an agreement to establish an ASEAN–China ‘hotline’ for maritime emergencies, adoption of the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea for the South China Sea, and a new deadline for drafting the official code of conduct by July 2017.

The new Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte, meanwhile, came into office keen to reset his country’s fraught political relationship with China. He was at first reluctant to press the matter of the tribunal, and later courted Beijing in a surprisingly enthusiastic fashion. During his October visit to Beijing, he announced his ‘separation’ from the US, and his idea for a new trilateral security relationship between Manila, Beijing, and Moscow. This represented a new opportunity for China to negotiate with the Philippines without US interference, despite misgivings among Chinese commentators regarding Duterte’s likely consistency and even longevity in office, given his controversial style. But above all, it meant that the Philippines did not run a campaign for international support for enforcement of the arbitral tribunal’s ruling, despite its resounding victory. China, for its part, claimed that eighty-seven countries supported its stance that the situation should be resolved through negotiation. Although this was an overstatement, it is true that only the governments of the US, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Philippines, and Vietnam publicly stated that the tribunal’s ruling should be enforced. Russia supported China’s position that the matter should be resolved without interference from third countries (presumably implying the US). China and Russia then conducted their first South China Sea–based joint naval exercise. This took place off the coast of Guangdong and far from any disputed areas, but it carried symbolic weight.

While international attention was focused on the South China Sea in 2016, China did not neglect its claims on the Diaoyu (or Senkaku) islands 钓鱼岛 in the East China Sea, currently administered by Japan, and also claimed by Taiwan. (See China Story Yearbook 2015: Pollution, Chapter 6 ‘Belt Tightening’) Chinese patrols by sea and air continued through the year, reaching a peak in September with the reported incursion of up to 230 Chinese fishing boats. Japan also complained through diplomatic channels in November about the operation of a Chinese drilling ship in disputed waters. Significant Chinese hydrocarbon exploration activity appears to be concentrated close to the median line. Prime Minister Abe and President Xi held a thirty-minute bilateral meeting in the margins of the G20 Summit in Hangzhou on 4 September. Xi reiterated his position that the East China Sea dispute must be resolved through negotiation, and Abe his view that a legal resolution was appropriate. It was their first meeting in over a year, and the atmosphere was, perhaps, a little improved. Both leaders cracked a smile for the camera.

Trumping the United States

If China had had to choose between the US presidential candidates it would have found it a challenge. Beijing has viewed Hillary Clinton as unfriendly since her speech on human rights at the UN Women’s Conference in Huairou in 1995, when she was First Lady. They also consider her as the architect of Obama’s Pivot to Asia policy, which they see as a

China-containment strategy. As secretary of state, she consistently promoted democracy and human rights — profoundly irritating the Chinese leadership. She also personally assisted the blind ‘barefoot lawyer’ Chen Guangcheng 陈光诚 who escaped illegal house arrest in Shandong, fleeing to the US Embassy in Beijing and then on to New York while Clinton was in China for the April 2012 Economic and Strategic Dialogue. In her book Hard Choices, Clinton recounted her negotiation of this tricky situation as an example of successful diplomacy that reflected the relative stability of the US–China relationship. But Chinese analysts have privately described it as a turning point: the public perception in China that the US could control the outcome of a domestic political issue compelled the leadership to adopt a more hard-line approach on national sovereignty and relations with the US. So Clinton might not have been Beijing’s first choice.

On the other hand, Beijing also fears unpredictability. Interestingly, there was some evidence in the run up to the election that Trump was a more popular candidate in China than elsewhere in Asia — certainly, some of the fake news circulating on American social media gained traction on Chinese social media as well, as did the notion that Clinton was ‘crooked’. Trump’s campaign statements heralding the possibility of a new American isolationism, meanwhile, seemed to favour Chinese domination of the western Pacific Ocean, and give it space to pursue a policy of gaining strategic centrality in Eurasia. What’s more, Trump’s populist but authoritarian style has shades of Xi Jinping and other leaders admired in China, such as Vladimir Putin. (See Forum ‘Chinese Americans for Trump, the “Genuine Petty Man” ’) On the other hand, he attacked China nearly as much as he did Mexico during the campaign — threatening a trade war, and accusing China of currency manipulation.

Any illusion that this might have been pre-election bluster was quickly dispelled. On 3 December, Trump took a call from Tsai Ing-wen, whom he called ‘President of Taiwan’, breaking with nearly four decades of diplomatic tradition on both counts (the direct contact, and the use of the phrase ‘President of Taiwan’ rather than an appellation such as ‘Taiwanese leader’). The President-elect’s ensuing series of tweets and then an interview with Fox News on 11 December made it clear that he was determined to stay on the offensive with China — and that he was making it up as he went along. He said that the US should make its ‘One-China Policy’ conditional on a larger deal including trade, apparently oblivious to this most important red line for China. The Taiwan issue, if badly played, is more likely to precipitate conflict in East Asia than any of the other many flashpoints. But Trump (and his advisors) apparently had no understanding of — or interest in — the fact that a resolution of Taiwan’s status would always be much more important to Beijing than good relations with the US. On 5 December, China, with Russia, vetoed a United Nations Security Council motion requesting a seven-day ceasefire to allow civilians to flee the Syrian city of Aleppo — essentially condemning many of them to death. This reversed an apparent trend of putting some distance between themselves and Putin’s support for Assad’s brutality, and may have been designed to show Trump that China can also play hardball.

And yet, Trump has also dismantled the Trans-Pacific Partnership on trade. This is good news for China, as it pushes its rival plan for a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. It could even mean the beginning of the end of the Asia pivot, which China finds directly threatening to its own security and ability to pursue direct diplomacy with its neighbours. Any weakening of American security guarantees to regional partners such as South Korea and Japan also creates opportunities for China to advance its interests in territorial disputes. China will be able to secure its dominant place in the region, not least through its massive program of economic diplomacy, the ‘One Belt One Road Initiative’.

Chinese commentators have publicly expressed reservations about whether China, now looking surprisingly like it may become the world’s most vocal proponent of free trade and climate security, is fully ready and willing to take on a leadership role in global governance. China’s GDP per capita, at around US$8,000, is still four times less than that of the European Union and around seven times less than that of Canada and the US. It still faces substantial challenges related to low economic development and high levels of inequality.

As for China’s military, as economic growth slows, so must the growth of the defence budget. It only increased by 7.5 percent in 2016, leaving it at 1.9 percent of GDP, which is below the NATO two percent target, and well below the US level of around 3.5 percent (or forty percent of total military spending worldwide). China’s per capita military spending is around twelve times lower than that of the US. China now has the ability to protect its interests in the region by imposing unacceptable costs on those who threaten them, but this is a far cry from being able to project power globally.

Still, it was only in 2014 that former President Obama accused China of being a free-rider on the international system. China has since then established its own international financing body — the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. It is the third biggest lender to the World Bank, and has made significant pledges to the United Nations, albeit limited to areas of specific Chinese interest. China even succeeded in persuading the International Monetary Fund to include the renminbi as a reserve currency in 2016, despite it not meeting the criteria of being freely tradeable and without capital controls — a significant change to the rules of the global economic order. Under Trump, the US may well remove further obstacles to China’s steady pursuit of incremental policies that will reshape and even control the global order.

Notes

Read the full text of the 12 July 2016 award online at: https://pca-cpa.org/content/uploads/sites/175/2016/07/PH-CN-20160712-Award.pdf

Position Paper of the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the Matter of Jurisdiction in the South China Sea Arbitration Initiated by the Republic of the Philippines, Beijing, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 7 December 2016, full text available online at: http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1217147.shtml

‘News Analysis: Shunji Yanai, manipulator behind illegal South China Sea arbitration’, Xinhuanet, 17 July 2016, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-07/17/c_135519215.htm

Veil of the Arbitral Tribunal Must Be Tore [sic] Down — Vice Foreign Minister Liu Zhenmin Answers Journalists’ Questions on the So-called Binding Force of the Award Rendered by the Arbitral Tribunal of the South China Sea Arbitration Case, Beijing, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 13 July 2016, online at: http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjbxw/t1381879.shtml

The Data Team, ‘The South China Sea’, The Economist, 12 July 2016, online at: http://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2016/07/daily-chart-5

Office of the Press Secretary, ‘Remarks by President Obama at U.S.-ASEAN Press Conference’, The White House, 16 February 2016, online at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/02/16/remarks-president-obama-us-asean-press-conference

Demetri Sevastopulo, Geoff Dyer, and Tom Mitchell, ‘Obama forced Xi to back down over South China Sea dispute’, Financial Times, 11 July 2016, online at: https://www.ft.com/content/c63264a4-47f1-11e6-8d68-72e9211e86ab

The text of the Declaration of Conduct of the Parties in the South China Sea is available on the ASEAN website at: http://asean.org/?static_post=declaration-on-the-conduct-of-parties-in-the-south-china-sea-2. The Chinese Foreign Ministry website also carries a report of the meeting at: http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjbxw/t1389619.shtml

Hillary Rodham Clinton, ‘Remarks to the UN 4th World Conference on Women Plenary’, delivered on 5 September 1995. The full text of her speech can be found online at: http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/hillaryclintonbeijingspeech.htm

Arshad Mohammed, ‘Clinton calls Mongolia a “model”, digs at China’, Reuters, 9 July 2012, online at: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mongolia-usa-idUSBRE8680GK20120709

Shi Jiangtao, ‘Why Trump carries less baggage in China: survey reveals candidate’s surprising popularity’, South China Morning Post, 5 November 2016, online at: http://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/2043316/clinton-wins-us-election-among-most-asians-support

Gene Gerzhoy and Nick Miller, ‘Donald Trump thinks more countries should have nuclear weapons. Here’s what the research says’, The Washington Post, 6 April 2016, online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/04/06/should-more-countries-have-nuclear-weapons-donald-trump-thinks-so/?utm_term=.fad564491f4e

Caren Bohan and David Brunnstrom, ‘Trump says U.S. not necessarily bound by “One China” policy’, Reuters, 12 December 2016, online at: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-china-idUSKBN1400TY

‘Can China overtake US to lead the world’, Global Times, 21 November 2016, available on http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1019172.shtml

Richard Gowan, ‘Is China ready to play a bigger role at the UN?’, Commentary, European Council for Foreign Relations, 6 February 2016, online at: http://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_chinas_incomplete_investments_in_the_un5094; and see also François Godement, ‘China’s Promotion of a Low-cost International Order’, European Council for Foreign Relations, 6 May 2015, online at: http://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_chinas_promotion_of_a_low_cost_international_order3017